Metropolitan

News-Enterprise

Friday, Dec. 29, 2000

_______________________

Accomplished

Attorney and Politician, He Now Presses for Excellence

on the Bench

By

ROBERT GREENE, Staff Writer

It

was just a mid-year meeting of the State Bar of California,

the kind that usually draws few participants. In fact, some

sessions were canceled due to lack of interest.

But

one conference room at the Costa Mesa hotel that hosted the

March 1999 event was packed. The reason: at the head of the

table was Burt Pines, judicial appointments secretary for

newly elected Democratic Gov. Gray Davis.

Hundreds

of lawyers, many of whom believed they had been shut out from

possible careers on the bench during 16 years of Republican

governors, hung on Pines’ every word. What were he and the

governor looking for? Was there a litmus test? Did only Democrats

have a chance?

The

responses would not have surprised those who have come to

know Pines personally and professionally over the years. People

who had seen him recreate the Los Angeles City Attorney’s

Office into an innovative, top-flight municipal law firm,

who knew his work for clients during his two decades as a

name partner in a Century City firm, who watched as he quietly

worked through crises behind the scenes at City Hall when

called on by officials years after he left government service—they

knew the new appointments secretary would respond with his

trademark blend of relaxed charm and concentrated intensity.

Everyone

is judged on his or her merits, Pines said. There are no litmus

tests. Avoid slipshod answers and grammatical errors. Neatness

counts.

"I’ve

always paid a lot of attention to good legal writing," Pines

added. "It’s a pleasure to read an application that’s the

product of good legal writing."

There

was a clear undercurrent. Sloppy writers, sloppy thinkers,

need not apply. Otherwise, consider signing up.

"With

Burt Pines, what you see is what you get," his friend and

former law partner Marshall Grossman says. "What you see is

an extremely bright, intelligent, hard-working, fair-minded

man who is totally committed to his state. He is one who insists

on a high level of competency and intellectual capacity. Very

careful and deliberate in decision-making."

Pines

and Davis were criticized at first for being a little too

deliberative in making appointments. July, 1999, which Pines

predicted would bring the first appointments, came and went.

Then August. September. The vacancies mounted.

But

nine Superior Court judges were named in October, and the

names have been coming ever since. The product of Pines’ deliberate

and meticulous review of applicants has been the appointment

of, so far, 74 trial and appellate jurists.

They

have earned near-universal acclaim for high quality and diversity.

The trial bench’s tilt toward prosecutors is slowly being

corrected, but Pines has recommended some prosecutors and

Davis has appointed them. The long drought of Democratic judicial

appointments is over, but there continue to be Republicans

selected as well.

Pines

deflects plaudits for the selections and instead cites the

high standards of Davis. But Davis called on Pines in the

first place because he knew of his old friend’s reputation

for insisting on high standards. Those standards have won

him public office, respect, admiration, and awards.

Pines

is this year’s Metropolitan News-Enterprise Person of the

Year.

Move

to Sacramento

Pines,

61, strides with obvious relish around the horseshoe-shaped

hallway running through the governor’s office on the first

floor of the historic state Capitol in Sacramento.

He

smiles as he points out the offices of Davis’ other top lieutenants.

Appointments chief Michael Yamaki, also a Los Angeles transplant.

The legislative secretary next door. The legal affairs secretary

across the hall. The communications secretary around the corner.

The governor himself.

"I

like being involved in the administration," Pines says. "It’s

fun knowing what’s going to happen before everyone else does.

I like being in the center of things."

You

would think from the remark and the boyish enthusiasm with

which it is uttered that Pines is still the ambitious USC

student, who was awarded a debating scholarship and became

president of the Trojan Young Republicans. Or the 20-ish assistant

U.S. attorney intent on putting away the crooks and making

a name for himself. Or the 30-ish private practitioner and

novice Democratic activist who stormed City Hall three decades

ago by ousting the 20-year incumbent city attorney.

But

the enthusiasm is real, and that may be part of Pines’ secret.

He has poured himself into every task he has undertaken.

Temporary

Sojourn

His

current job, for example. At first, when Davis called on him

to help lead his transition team after the November 1998 election,

Pines made plans for a temporary sojourn to Sacramento before

returning to his lucrative Century City practice at Alschuler,

Grossman & Pines.

Then,

when Davis asked him to stay on as judicial appointments secretary,

he decided spending more time in Sacramento wouldn’t be so

bad, as long as he could shuttle back to his firm, his clients,

his community leadership posts and his friends.

He

could have done it, too. No law prevents it. But Burt Pines

is not one to do anything half-way.

"Burt

sought counsel from past judicial appointment secretaries,"

Marshall Grossman says. "Burt came to the conclusion that

while he could continue to have a relationship with the firm

of counsel, it would present an apparent or potential conflict

of interest to do that. As is typically Burt’s manner of doing

things, he made a principled decision in the public interest."

So

Pines and his wife, Karen, who had lived in the San Fernando

Valley for decades, packed up and moved to Sacramento.

He

explains that as he was working part-time helping Davis fill

key spots in his administration, he "just became very enthused

and excited" about the work, and about the chance to help

the governor appoint new judges.

"And

after a short time, I decided I’d like to be a part of this,"

Pines explains. "As I began to learn more about the position

and the responsibilities, I realized that I could not do this

job and continue in private practice. Besides, it’s difficult

to work out of Los Angeles. This is where my staff is. I wanted

to be part of the administration. I didn’t just want to be

part of the L.A. office and hear about things later."

He

says he and Karen also like the slower pace, the more courteous

drivers, the water instead of concrete in the rivers.

The

Pineses got themselves a place on the American River in Carmichael,

a short drive from the Capitol. Burt Pines, as one might expect,

has timed the transit carefully.

"It’s

17 minutes to the office," he notes.

Brisk

Pace

In

retrospect, the pace of appointments to the bench has been

brisk, compared with the number of vacancies filled in the

first full year of then-Gov. Pete Wilson’s term. But before

Los Angeles Municipal Court Judge Jon Mayeda’s promotion to

the Superior Court was announced in October 1999, impatient

observers and applicants were getting a little restless. Pines

reminded all who would listen that Davis takes judicial appointments

seriously and would not be rushed, but with numerous vacancies

remaining in the governor’s own office as well as on the bench,

there was increasing pressure for action.

Then

reports began circulating that Pines was grilling applicants

over the death penalty. The rumor went that no one who opposes

the death penalty could expect to be appointed.

Pines

repeated: no litmus tests. But he also took pains to note

that Davis insists on promoting public safety, a term observers

took as code words for a death penalty litmus test.

The

first appointments silenced the critics for a while. Mayeda

was a safe and obvious choice, given his outstanding credentials

and the simple fact that he would soon become a Superior Court

judge anyway because of court unification. Few could quarrel

with Morrison & Foerster partner Dennis Perluss, a former

deputy general counsel for the Christopher Commission. For

the waning days of the Los Angeles Municipal Court, there

were Assistant U.S. Attorney Leslie A. Swain, former Los Angeles

Police Commission President and interim inspector general

Deirdre Hill, and Fourth District Court of Appeal senior attorney

Richard Rico.

Moving

Arthur Gilbert from Court of Appeal justice to presiding justice

was neither surprising nor controversial, but simply solid.

The elevation of Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Candace

Cooper to the Court of Appeal was applauded.

Pines

was congratulated. Davis was off the hook.

But

only for a few months. The following February, on the heels

of his comment that elected legislators were there to implement

his vision, Davis told a gathering of governors that the judges,

too, should expect to toe the line.

"They

are not there to be independent agents," Davis was quoted

as saying. "They are there to reflect the sentiments that

I expressed during the campaign."

If

they arrive at a conclusion that differs from the governor,

he said, "they shouldn’t be a judge. They should resign."

It

was a shocking statement given the fact that judges are, of

course, expected to be independent from the governor. Davis

issued a retraction, but it was left to Pines to do the delicate

soothing of ruffled feathers.

In

a letter to the editor of the Los Angeles Times, in wording

similar to letters sent to newspapers around the state, Pines

wrote that Davis’ goal to appoint was judges of the "highest

caliber and integrity."

"On

behalf of the governor, I conduct the interviews of the candidates,"

Pines wrote. "I probe their background and experience, their

goals and aspirations, their reasons for wanting to become

a judge, their judicial philosophy and their willingness to

follow the law irrespective of their personal beliefs. I also

seek to ascertain if the candidates have generally similar

views to those of the governor, particularly his commitment

to public safety."

Yes,

Pines explains months after the flap, he does ask applicants

about the death penalty and their willingness to impose it.

"This

governor has a strong commitment to public safety," Pines

says. "And I have to be comfortable that the candidates I

recommend to him share that commitment. He does not want to

appoint judges that are going to be soft on crime. I do ask

them about their views on three strikes. And a host of other

questions."

A

quarter of a century ago, Los Angeles City Attorney Burt Pines

might not have qualified for a Gray Davis judicial appointment.

He staffed his office with the same types of people Davis

now wants to see as judges—talented women, minority and gay

lawyers, people of diverse backgrounds, idealistic thinkers

and pragmatic achievers. But he opposed the death penalty.

Of

course, that was the era in which Gray Davis was chief of

staff for Gov. Jerry Brown, who appointed Rose Bird and other

death penalty opponents to the state Supreme Court.

Pundits

have written that Davis wants to avoid at all costs the public

outrage spurred by the Bird court’s steady rejection of death

verdicts. That outrage resulted in the ouster from the bench

of the late chief justice and two of her Brown-appointed colleagues.

But

Pines’ change of stance on capital punishment is not a result

of political expedience. He cannot recall just when he changed

his mind, but he says it was at least 20 years ago.

"I’ve

just seen such horrible acts by human beings against other

human beings that I just felt that people who chose to commit

such acts would forfeit their right to life," Pines explains.

"I’m a strong proponent of the death penalty."

Actually,

Pines’ death penalty stance may not have disqualified him

after all, and his experience may hold a lesson for judicial

hopefuls who will be asked if they can follow the law without

regard to their personal qualms. Pines opposed the war in

Vietnam, but as an assistant U.S. attorney he prosecuted draft

evaders.

"I

thought that was my responsibility," he explains. "That was

the job that I had."

Mother

Arrested

Any

elected official gets his or her share of negative newspaper

stories, but there is one headline that sticks in Pines’ mind

from his tenure as city attorney:

"Pines’

Mother Arrested for Gambling."

He

shrugged it off at the time. He’s not his mother’s keeper,

he told reporters, and all law-breakers are treated equally.

Besides, he knew all about his mother’s penchant for card-playing.

There

was no hint of embarrassment or shame.

But

today, Pines acknowledges that as far back as he can remember,

he wanted to rise above a background he calls "humble."

An

only child, he lived with his grandparents in a small Burbank

apartment. His room was a converted dinette. His mother, Ruth

Pines, worked on airplanes for Lockheed during World War II,

usually taking the night shift so she could be with Burt during

the day.

Later

she worked in sales, traveling with a crew of women selling

pots, pans and similar items door-to-door. Still later, she

managed a bridge club. The kind where money was wagered.

Early

on, her interest in cards had led her to another gambler,

Charles Landeau. They married, and Burt was born, but when

he was just a year old the couple divorced. Burt’s mother

had her son’s last name changed to Pines, her maiden name.

"I

really didn’t know my father," Pines says. "He was a gambler

and a bootlegger. Not really interested in family."

But

Pines resists being pegged as the child who strove to succeed

to compensate for a less than ideal family life.

"There

were many factors that played a part in that," he says. "It’s

hard to analyze one’s psychology. I think early on I wanted

to excel. To do something worthwhile. I think I wanted to

go beyond my origins. Certainly in my family there was a stress

on education. I’ve wanted to excel my entire life."

Los

Angeles High School classmate Marshall Grossman recalls Pines

as being a fairly serious student, interested in student government

and perhaps a future in politics.

"We

were friends," Grossman says. "But we didn’t hang out in the

same crowd."

Pines

was elected student body president.

At

USC, he debated and majored in philosophy. And there was that

Young Republicans leadership post. It was 1960, not a time

for young Republicans.

He

jokes now that he doesn’t usually admit to his old Republican

affiliations, but that since 40 years have passed it may now

be "okay" to mention.

Besides,

he asserts, Republicans were more moderate in that era. And

law school at New York University (full scholarship), during

the Kennedy era, put an end to his Republican days anyway.

Federal

Prosecutor

On

graduation in 1963, the offers flooded in from the big firms,

but Pines had spent a summer clerking at a New York firm and

he knew he wanted something different. He wanted courtroom

time. So he accepted an offer from the U.S. Attorney’s Office

for the Southern District of California, which was the name

then of the federal prosecutor’s office headquartered in downtown

Los Angeles.

But

first there was the bar exam. He got himself an apartment

on Sycamore and Beverly to study, but he took a shine to his

upstairs neighbor, a young lady who had moved to California

to escape the Ohio winters.

When

the neighbor would come home from work and Pines needed a

study break, he would tap on the ceiling with a broomstick.

Two stomps in response mean "I’m busy." A single stomp meant

come on up.

Despite

the distraction, Pines passed the bar, and he and Karen married.

Meanwhile,

he got his courtroom time—35 jury trials in just under three

years. The office covered San Diego and Imperial counties

as well as Los Angeles, and he and his 17 colleagues occasionally

rode circuit to places like Fresno. He prosecuted car thieves,

check forgers, bank robbers.

"As

I look back on my career, I think that some of my greatest

days were in that office," Pines recalls. "There was an esprit

de corps. We all felt we were on a mission to protect the

public."

In

a sense, Pines’ boss was Robert Kennedy. But it wasn’t until

he left the U.S. Attorney’s Office in 1966 to join Kadison

& Quinn that he became interested in Democratic Party

politics. That’s when he befriended a Van Nuys lawyer named

Chuck Manatt.

Manatt

suggested that Pines get involved in the 1969 John Tunney

for Senate campaign, and he took the advice and threw himself

into it. He wound up co-chairing the speakers committee with

another political novice—Gray Davis.

The

Kennedy-esque Tunney toppled incumbent Sen. George Murphy,

and Pines then helped get Manatt elected chairman of the state

Democratic Party. Pines became counsel to the party, and cemented

the contacts that made his 1973 challenge to veteran City

Attorney Roger Arnebergh possible.

Arnebergh

had been virtually handed the office in 1953, when incumbent

Ray Chesebro announced his candidacy for a sixth term, scaring

off challengers, then whispered to Arnebergh that he should

file. Arnebergh filed, Chesebro dropped out and endorsed him,

and Los Angeles didn’t see a real election for city attorney

for another 20 years.

Smaller

Firms

Meanwhile,

Pines had moved around a bit. When Kadison & Quinn merged

with another firm to become Kadison, Pfalezer, Quinn &

Rossi, it became—with 14 lawyers—too big for Pines’ taste.

He set up a litigation practice on the Westside with Schwartzman,

Greenberg and Finberg, then later formed Dunn & Pines

with now-Superior Court Judge James R. Dunn.

"I

enjoyed private practice and felt proud that I made it on

my own," Pines says. "I felt that this wasn’t enough in life.

I felt that I wanted to make a contribution. I felt city attorney

was an office I could win if everything went right. If things

broke right."

Things

broke right. Arnebergh’s office was fairly low-profile. A

Pines poll showed that only about 25 percent of residents

recognized his name—but the majority thought he was doing

a bad job!

Then

there was the growing Watergate scandal, and a general dissatisfaction

with incumbents. There was a weariness of Mayor Sam Yorty,

and a feeling that it was now time for African American mayoral

candidate Tom Bradley.

Pines

notes, too, that the Los Angeles Times decided to cover his

campaign. Plus he benefited from the expert campaign piloting

of Bob Thomson, who went on to become his chief deputy. He

got help, too, from Manatt, who offered his expertise.

"It

was very clear to me that timing is almost everything in politics,"

Pines says, "and the timing was right."

Having

won the office, Pines set about reorganizing it from top to

bottom. Gay lawyers, for the first time anywhere, were welcomed

into the fold. As Bradley opened city commissions to women

and minorities, Pines did the same in the City Attorney’s

Office.

| Pines

addresses a crowd during is days as city attorney of

Los Angeles. Seated are, from left, Gov. Jerry Brown

and Mayor Tom Bradley. |

He

cites with pride some of the young lawyers who helped him

put the office together. Aileen Adams, now Davis’ secretary

of secretary of State and Consumer Services. Mary Nichols,

secretary for resources. Peter Dunn of Korn/Ferry.

And

a host of judges—Dion Morrow, Judith Ashmann, Sally Disco.

"The

salary spread was not that great between what we could hire

people at and what firms were paying," Pines explains. "We

wanted to create the best public law office in the country.

There were not the opportunities for women and minorities

in the private sector that there are today. We were the beneficiary

of that."

It

was also a time when the city had money in the budget. Pines

set up a consumer fraud section, an environmental protection

section, a hearing officer program in which paralegals handled

citizen complaints against police.

Then

as now, Pines was meticulous, deliberate. But he showed he

could also move. Leading a crew of television cameras, he

stormed a slum apartment to crack down on code violations

that were forcing tenants to live in squalor. He brushed aside

Police Chief Ed Davis’ insistence that criminal complaints

against his officers be pursued only administratively.

"We

could not have a different standard for police officers from

everybody else," Pines explained. "This did not ingratiate

me with the rank and file."

Burt

and Karen Pines had three young children, sons Adam and Ethan

and daughter Alissa. Adam Pines, now a lawyer at Manatt, Phelps

& Phillips, the firm started by Manatt and the former

home of ex-senator Tunney, remembers visits to his father’s

office.

| Los

Angeles City Attorney Burt Pines relaxes at home with

his family. From left are wife Karen Pines, daughter

Alissa, and sons Ethan and Adam. |

"It

always looked like fun," he recalls. "As I got older, I

liked the way he got along with people. I liked the way

people treated him. Although parties got to be a hassle,

because we had to wait while he talked to everybody."

A

concern for family life led the Pineses to move to Shadow

Hills, the horsey country in the Northeast San Fernando Valley.

There they rode horses and cared for chickens, peacocks, sheep

and rabbits. The kids mended fences. They would take weekend

family horseback rides. They lived the semi-rural life a half-hour’s

drive from City Hall.

Family

remained important to the man whose own father walked out

when he was an infant. Pines reserved Sundays for family,

even when he sought the Democratic nomination for attorney

general in 1978. Supporters urged him to give up the family

time to focus on the tough fight against Yvonne Brathwaite

Burke. But he wouldn’t do it.

Perhaps

because of his Sundays off, perhaps because Burke raised a

two-year-old incident in which a Pines deputy authorized the

shredding of several tons of police records, Burke came from

behind to win the nomination. She was defeated in the general

election by George Deukmejian.

If

politics meant giving up family time, Pines had had enough

of it. He had promised to stay only two terms, and although

he was lauded for the job he did doing those eight years,

he was more than happy to keep the promise.

"I

felt that I had made a contribution and accomplished much

of what I wanted to do," Pines says. "I also felt that after

two terms there ought to be a change. I decided not to go

on to pursue other elective offices because I was not prepared

to pay the price in terms of my family life."

After

leaving office, Pines took his family on a road trip of national

parks around the West.

Grossman

Calls

Heavily

courted by firms all over Los Angeles even before leaving

office, Pines heeded the invitation of his old high school

friend, Marshall Grossman. Alschuler & Grossman was a

small but prominent Century City firm. Alschuler, Grossman

& Pines became a Los Angeles powerhouse.

"Burt

selected to join a smaller firm because he enjoys the camaraderie

and professional relationships," Grossman says. "He brought

a broadening of the face of the firm. We were able to distinguish

ourselves in an area other than commercial litigation."

Pines

cemented relationships he had built over his career and became

counsel to Korn/Ferry, United Airlines, U.S. Airways, and

other corporate giants. He took his place in the leadership

of the Greater Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce. And he kept

his contacts at City Hall.

Then-City

Administrative Officer Keith Comrie remembers working closely

with Pines on various crises and developing a deep respect

for him.

"He’s

like the old Dr. Kildare," Comrie says of Pines. "He has a

very nice manner about him. But he’s very intense. Extremely

knowledgeable."

When

Comrie became engaged, several years after Pines left office,

he and his financee had no doubt whom to call to perform the

ceremony. They got Burt Pines.

"Apparently

ex-public officials can be certified for a day to perform

marriage ceremonies, and my wife and I were unanimous," Comrie

says. "We knew Burt Pines would have the best sense of humor

for a second marriage. So he did it."

His

City Hall ties also were of a more official kind. He advised

Mayor Richard Riordan on a number of issues. He counseled

the mayor during the flap over Police Chief Willie Williams’

rebuke by the Police Commission for half-truths about gambling

trips to Las Vegas. He headed in inquiry into the actions

of top Riordan aide Michael Keeley, when Keeley overstepped

his bounds by sharing litigation strategy with the city’s

opponent. Other roles were more, as Riordan puts it, "below

the radar."

"He’s

someone I’ve always been able to turn to for advice," Riordan

says of Pines. "He has a great deal of experience and remains

a valuable asset to the city."

Pines

has not always seen eye-to-eye with the current mayor, however.

When Riordan pressed charter reformers to replace the elected

city attorney with an appointed counsel and an elected prosecutor,

Pines lobbied hard for keeping the office as-is.

Davis

Supporter

Although

retired from public life, Pines remained politically active.

He was a staunch supporter of Davis as a candidate for the

Legislature, lieutenant governor, and governor. So it was

no surprise, really, that Davis called on him to join the

administration.

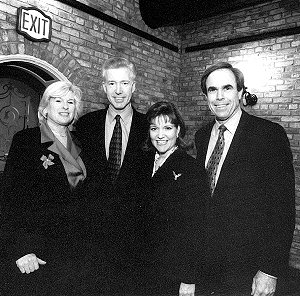

| Socializing

are First Lady Sharon Davis, Gov. Gray Davis, Karen

and Burt Pines. |

To

take the sting out of leaving Los Angeles, he got a place

in Paradise Cove for the occasional weekend trip home. But

he says he and Karen Pines spend more and more time in Sacramento,

working during the week, horseback riding on the weekends.

Karen

Pines, a marriage and family therapist in the San Fernando

Valley, landed a part-time counseling job at American River

College, counseling welfare recipients transitioning to work.

Then Davis appointed her to the to Behavioral Sciences Commission,

and the Assembly speaker appointed her to the Commission on

Aging. She became an adjunct professor at Cal State Sacramento.

Burt

Pines is absorbed in judicial appointments.

"I

really like this job," he says, noting that he has the opportunity

to meet so many people who have risen so far from such—there’s

that term again—humble origins. He has recommended, and Davis

has appointed, judges from all socio-economic backgrounds

and walks of life. But the ones Pines mentions are the children

of Japanese American internment camps, the children of migrant

farm workers, and the others who have risen above their backgrounds.

In

the interviews, Pines says, he likes asking people about themselves.

He wants to get a feel for who they are, how they think.

Patricia

Schnegg, the former Los Angeles County Bar Association president

who was appointed to the bench earlier this year, says Pines

is true to his word. No litmus tests.

"There

was really a wide ranging discussion of a variety of topics,"

Schnegg says. "It came through that he takes his job very

seriously. I didn’t feel there were any right or wrong answers,

that it was more of an exchange than anything else."

But,

she notes, it’s also clear that he is meticulous. He did his

homework.

"He

knew your PDQ through and through and he didn’t have to refer

to it," she says.

Several

weeks ago, Pines took part in the Women Lawyers of Los Angeles

program on "How to Become a Judge." Again, hundreds of prospective

judges crowded into the room just like at the forum Pines

first conducted for the State Bar in March 1999, before Davis

had sent any names to the Judicial Nominees Evaluation Commission.

This

time, there was a track record. More than 50 appointments.

But the message was the same.

"This

is a merit-based system," he said. "It doesn’t matter if you

donated to the governor."

No

litmus tests. But remember, the governor is a moderate with

a strong commitment to public safety.

"He’s

more likely to appoint people who reflect his views than not,"

Pines told the crowd. "That’s what governors do."

And

another thing. Neatness counts.

"I’ve

been in practice a long time and I do give a lot of attention

to detail," he said. "I can’t help but be concerned when I

see applications replete with grammatical and spelling errors.

I don’t know why we have applications with spelling mistakes.

Please give this your best shot."