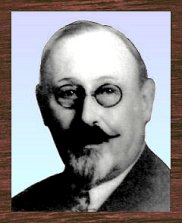

CHARLES

S. BURNELL

Los Angeles

Superior Court Judge, 1921-49

Wednesday, April 18, 2001

Page 7

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

Charles S. Burnell: a Judicial Tyrant of Many Years Past

By ROGER M. GRACE

Back in the days before there was a Commission on Judicial Performance, before it became acceptable for a lawyer to challenge a judge at the polls, there was little that could be done about a cantankerous jurist who continually blurted out nasty and prejudicial comments. A source of particular consternation to the bar and to fellow judges for a three-decade period in the first half of the last century was just such a judge, one Charles S. Burnell. Near the end of his career, two justices in a Court of Appeal opinion called for his removal from the bench either by a judicial commission, based on mental disability, or by the Legislature, through the impeachment process.

Burnell appears from recitations in the opinions to make A. Andrew Hauk, a senior judge of the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California known for his inappropriate asides, seem a pussycat by contrast.

The California Supreme Court took Burnell to task in People v. Mahoney (1927) 201 Cal. 618. That case concerned the manslaughter conviction of a contractor stemming from the death of a person who was crushed by a grandstand that collapsedóallegedly due to shoddy constructionóduring the 1925 Tournament of Roses parade. On appeal, the contractor pointed to 23 instances of alleged misconduct on the part of Burnell in the form of comments he made.

|

|

CHARLES

S. BURNELL |

For example, an attorney took the stand to testify as expert on construction, a field he had been in some years back. Burnell took over the questioning. This colloquy took place:

The Court: Letís put it this way, Mr. Gardner: From your experience as a builder and contractor of about eight years obtained thirty-four years ago, would you say that the stand in question was constructed in a safe and workmanlike manner?

A. Absolutely so.

Q. What happened to it, do you know?

A. I know it fell down. Butó

Q. That is all. You have answered the question.

A. Yes. I donít think it is hardly fair when the question has beenó

Q. Now, you are not here to say whether a question that is asked is fair or not, andó

A. I understand, Your Honor.

Q. ... the fact that you are an attorney of the court and an officer of the court makes it all the more wrong for you to attempt to make such a statement as that, and if it occurs again I shall hold it a contempt of court, just as I would with anybody else who is insulting or doesnít show the proper respect for the court. Now, you are here as a witness to answer questions.

A. I understand. I wantó

Q. Never mind what you want. You are here to answer questions, and when you have answered the questions close your face after you have answered the question, and donít let me hear any more remarks of that kind. If you do you will be up here in a structure that will bear a whole lot more weight than any grandstand is intended to bear.

Sweet guy, eh?

A short time later, Burnell announced: "Well, I guess we had better take the afternoon recess, ladies and gentlemen, we donít want to tire our noted expert out."

The opinion observed: "Realizing the eagerness with which juries grasp the suggestions of the trial judge, we can appreciate the fact that no weight would be attributed by them to his testimony after the remarks just quoted."

The attorney for a co-defendant of the contractor was asking questions of the chief of police when Burnell tossed in a wisecrack. Hereís the transcript:

Q. He is a man who bears a good reputation in Pasadena?

A. Excellent. ...

Q. For his truthfulness?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Honesty?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Integrity?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. By the Court: And chastity?

A. Yes, sir.

The Court: We might as well get them all in.

When a defense lawyer, started to make an objection, Burnell piped up: "Wait just a minute. I think Mr. ó is laboring with an objection." (The Supreme Court eliminated the lawyerís name.) A short time later, Burnell continued with his fun, observing: "Just a moment. Mr. ó is a little bit slow in getting started, so we will have to give him a little chance to make his objection. Go ahead, Mr. ó I can always tell from the motions you are making there is an objection about to come forth." The lawyer said, "Yes, Your Honor," prompting the judge to comment: "Now you have passed through the preliminary pain, give birth to it."

A defense lawyer opined that photographs of the accident scene were inadmissible unless the photographer authenticated them. Burnell overruled the objection, unleashing this diatribe:

"Well, it seems to me it is an idiotic objection, to be frank about it. All right, bring the photographer here, since they seem to want to make you a little more trouble. Do you want them to bring the camera here?...You want him to bring the same shoes he had on when he took the picture? How about the gum he was chewing? Do you want him to pick that up again? Just about as sensible. I havenít much patience with an objection which is made just for the purpose of making objection, when there doesnít seem to be a scintilla of sense in making them...."

Other comments by Burnell in a similar vein are also quoted in the opinion.

![]()

In reversing, the Supreme Court said:

[T]oo strong emphasis cannot be laid on the admonition, a judge should be careful not to throw the weight of his judicial position into a case, either for or against the defendant. It is unnecessary to cite the cases bearing on this subject. It is a fundamental principle underlying our jurisprudence. When, as in this case, the trial court persists in making discourteous and disparaging remarks to a defendantís counsel and witnesses and utters frequent comment from which the jury may plainly perceive that the testimony of the witnesses is not believed by the judge, and in other ways discredits the cause of the defense, it has transcended so far beyond the pale of judicial fairness as to render a new trial necessary.

A string of smart-aleck comments by the judge aimed at defense lawyers was recounted in People v. Reese (1934) 136 Cal.App. 657. Convictions of the defendants on four counts of grand theft by false pretenses were reversed based on a combination of weak evidence and Burnellís injudicious utterances.

"Extended comment would seem to be unnecessary," the per curiam opinion said. "In cases too numerous to properly admit of citation thereof, because of judicial misconduct that was insignificant compared to that which so unmistakably appears in the instant case, the respective judgments therein were reversed."

![]()

The next occasion the Court of Appeal had to scrutinize Burnellís propensity for popping off was in People v. McNeer (1935) 8 Cal.App.2d 676. The defendant in that case had incurred a gunshot wound, and the bullet remained lodged in his head, resulting in blindness in one eye, loss of hearing in one ear, and partial paralysis. During the trial, he emitted noises and uttered pleas for help. As reported in the opinion, the judge protested:

"You will have to keep quiet; this sort of thing will not be allowed at all, Mr. McNeer. This sort of theatricalism has got to stop right now, and you might as well know it. Canít you do something with your client, Mr. Hahn?"

In later remarks, Burnell referred, in the presence of the jury, to "three witnesses, all of whom were stipulated to be qualified expertsÖ[having] agreed that the defendant was sane, and that he was malingering or faking." Still later he said: "Gentlemen, apparently it is going to be impossible to go ahead with the case this morning. I am informed that the defendant has been putting on his show in the presence of the jury, and there is no use trying to go ahead with the case now, so we will have to take a recess until 2:00 oíclock."

The court held: "Under all of the circumstances shown by the record in this case, the actions of the trial judge prejudiced the rights of the defendant, requiring a reversal of the judgment."

![]()

Then came People v. Earl (1935) 10 Cal.App.2d 163. Burnellís cross-examination of a defendant was disapproved, though a reversal did not result. The following portion of the opinion was to be quoted 13 years later in an opinion excoriating Burnell for his misconduct through the years:

Appellants vigorously assert that the trial court was guilty of misconduct in his remarks made while defendant Ryan was on the witness stand and in his questions directed to this defendant. The record shows that the trial judge made this statement: "I have tried to get this witness to speak like a man, but it doesnít seem to do any good. He doesnít seem to want the jury to hear his testimony." A little later in the record the following questions by the court and answers by the defendant Ryan appear: "Q. You did tell the truth then occasionally, did you?...Q. What was your idea in telling all of those lies? A. I did not know what to say. Q. Did it ever occur to you to tell the truth? A. Yes, I tried to make it lookó Q. How did you happen to be telling all those lies on this particular case? A. I did not know what to say. Everyone was firing questions at me. Q. When people ask you questions, is it your custom to lie? A. No, it hasnít been. Q. This was just a special time, at that particular time you concluded to lie part of the time? A. I did not know what to say. Q. Didnít it ever occur to you to tell the truth? A. I told the truth as much as I knew about it. Q. That is all I wanted to ask you." The statements made by the court and the questions asked were not proper.

![]()

A man convicted of murder appealed in People v. Johnson (1935) 11 Cal.App.2d 22 on the sole ground of misconduct by the prosecutor and by Burnell. The asserted misconduct occurred when the prosecutor cross examined a defense witness and pointed to discrepancies between his testimony at a coronerís inquest and his current testimony, querying: "[W]hen were you lying, then or now?" Burnell chimed in, saying (in front of the jury): "I think this witness should be held for a possible perjury complaint ...; and he was either lying then or is lying now, and either way it is, it seems to me he should be held for perjury."

The Court of Appeal observed:

"No citation of authority or recitation of principles of judicial decorum is necessary to brand this conduct of the trial court as improper and tending to prejudice defendantís rights. When the court belatedly attempted to remedy his judicial faux pas by telling the jury that he did not Ďwant to be deemed as having made any statement as to the truth or falsityí of the testimony of the witness in question, it is obvious that the wrong done could not be cured."

Nonetheless, it found the error to be harmless.

![]()

Ten years after the Supreme Court reversed Burnell in People v. Mahoney for conduct that was apt to prejudice the jury, the judge was reversed by the Court of Appeal in Anderson v. Mothershead (1937) 19 Cal.App.2d 97, in part for the same reason.

This portion of the transcript was offered as one of the 10 instances of misconduct claimed by the defendant:

Q. By the court: You saw Mr. Andersonís car when you were a block and a half away?

A. Just about that.

Q. How did you happen to hit it then?

A. I was trying to dodge an oncoming car. Mr. McGee: We will mark this M-1.

The Court: So you took a chance as to which car you would hit, and you hit Mr. Andersonís car.

A. I did not hit head on.

Q. In other words, to save you being hit by this other car; you chose to hit Mr. Andersonís car?

A. I did not choose to hit any car; I thought I could stop before I would hit anything or be hit.

Q. But you did hit Mr. Andersonís car, and Mr. Andersonís car was parked?

A. Yes.

Q. And you had had two drinks at least?

A. Yes.

The Court: That is all I want to know.

Mr. McGee: May we approach the bench?

The Court: Yes, if you want to, but it seems that you ought to be able to try a lawsuit without continually coming up to the bench to ask how to try it.

Mr. McGee: That wasnít my purpose.

The Court: Very well. (At which time the following proceedings were had at the bench and outside the hearing of the jury):

Mr. McGee: The defendant makes a motion for a mistrial on the grounds of prejudicial misconduct of the court in the questions just asked of the witness.

The Court: The motion is denied.

As the appellate court sized it up:

"It would be but natural for the jury to believe that the judge looked with disfavor upon defendantís statements concerning the circumstances of the collision. The error was made worse by the courtís remarks which tended to discredit defendantís counsel with the jury."

In my next column, Iíll relate some more of Burnellís antics, as reported in appellate decisions in the 1940s.

Copyright 2001, Metropolitan News Company