Metropolitan News-Enterprise

Wednesday,

October 15, 2003

Page

7

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

Mablean Ephriam: Well-Regarded Lawyer Portrays

Crass Judge on Television

By

ROGER M. GRACE

On a recent session of television’s “Divorce

Court,” an Anglo male,

married to a Hispanic woman, noted that he was referred to by her family as a

“cracker” (a slur akin to “honkey” or “whitey”). Mablean Ephriam, playing the

judge, quipped: “Don’t y’all know that crackers and beans go together?”

Was that inappropriate remark a slip? Hardly.

Tossing out one-liners like that typifies Ephriam’s approach.

I bounced that particular wisecrack off David

Rothman, the retired Los Angeles Superior Court judge who’s known as the guru

of judicial ethics in California.

If those words were uttered by an actual member of the bench, Rothman said, “the

judge would be in deep trouble.”

Inappropriate use of humor, he noted, is a

frequent basis for discipline.

Rothman, author of California Judicial Conduct

Handbook, expressed the concern that judicial misconduct on a mock courtroom

show might “give the public a misimpression of how judges actually behave.”

While “Divorce

Court” does not purport to

depict California

proceedings, it is difficult to believe that conduct by an actual judge which

paralleled that displayed by Ephriam would be tolerated in another state any

more readily than it would be here.

Ephriam, a graduate

of Whittier College School of Law, was admitted to the State Bar of California

in 1978. She served for five years as a Los

Angeles deputy city attorney,

and since 1982 has been in private practice. Primarily, she’s been a family law

practitioner, also handling mediations. Ephriam has been a hearing examiner for

the City of Los Angeles Civil

Service Commission.

|

|

|

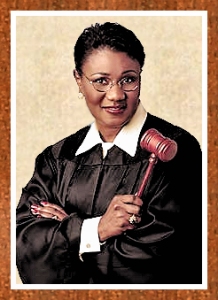

MABLEAN

EPHRAIM

Los

Angeles Attorney, Mediator

Star of the third

version of television's "Divorce Court"

|

|

|

The Women Lawyers Association of Los Angeles in

1993 conferred its Distinguished Service Award on her for such contributions as

having co-founded the Harriet

Buhai

Center

for Family Law. The Los Angeles County Bar Assn. bestowed the Spencer-Brandeis

Award on Ephraim in 1996.

She’s a past president of the Black Women

Lawyers.

Her credentials are impressive.

Yet, the Mablean Ephriam seen on television has

a big mouth and abysmal judicial demeanor.

On last Friday’s show, a

wife said she spotted hickies on her husband’s neck which she hadn’t caused.

Ephraim told the husband:

“Let me see the hickies on your neck. Come on up

here so I can put another one up there. Not from kissing you, trust me.”

Last Wednesday, Ephriam queried of a spatting

couple why they had managed to stay together. The husband pointed out that they

had children. “But how did you have children with all this going on?” she

asked. The husband explained to her how it’s done: “You have sex, your honor.” Ephriam

responded: “Oh! Is that how you have it? Tell me something.”

In another recent case, an ex-wife claimed her former spouse

forced her to gain weight. “Judge” Ephriam sided with the woman.

“You were a cheater and a liar,” she shouted at

the former husband at one point. At another point, she used the line: “This is

cockamamie bull and it’s just an excuse for him to go play around.”

The ex-wife mentioned that her erstwhile spouse

had extramaritally fathered two children; the man acknowledged this. “Two

babies,” Ephriam recited—proceeding to scream at the man: “In case you didn’t

know.”

She said this of the male litigant:

“If I seen him lying in bed with a woman right

now, he’d be denying that I was seeing what I saw.”

In another case that day, a woman suspected her

former husband, a mechanic, of having had an extramarital relationship with a

customer. Ephriam quipped, loudly (as always): “There’s all kinds of spark

plugs and all kinds of tune-ups, you know.”

In a third case, she used these lines: “You’d

better pick up your foot because you’re stepping in something” and “You must

think I’m a ding-dang fool and just stepped off a turnip truck.”

On another installment, the ex-husband was

accused of having had extramarital sex with more than 2,000 women over a

16-year period. Ephriam defined his “type” of woman as all persons “as long as

they had a hole.”

The litigant said, “I always used a condom,” to

which Ephriam responded: “Not for oral sex.”

This is a sampling of Ephriam’s

remarks based on my having turned her program less than a dozen times.

On last Thursday’s “Divorce Court,” a woman who was suing

for divorce was asking the judge to order her husband to relinquish a bunk bed.

He had bought it, before they separated, for her two daughters by a previous

relationship.

Property

was all that was in issue.

But

sex was the theme of the program, as it customarily is.

The

petitioner said her husband wasn’t pleased with her wifely performance. This

dialogue ensued:

JUDGE:

What didn’t you know how to do right?

WIFE:

Well, I couldn’t—for one, I didn’t give enough sex. For another, the house was

never clean enough. For another, it wasn’t done exactly how he wanted it.

JUDGE:

You didn’t give enough sex. Let’s start with that.

WIFE:

Four times a week. You know, pretty normal.

JUDGE:

How long did that go on?

HUSBAND:

Long time. Until she got pregnant.

JUDGE:

Well, I don’t know how long that was. How long did you date? How long did you

have sex before you got pregnant?

WIFE:

Eight months.

JUDGE:

So, for eight months in your relationship, four times a week. Then what

happened?

WIFE:

When he wasn’t getting it when he wanted to, night after night after night,

very uncomfortable, with his hands all over me, in between my legs, fondling my

breasts, you know, doing whatever he needed to.

JUDGE:

Trying to arouse you?

WIFE:

Yeah, basically, basically. In the middle of the night when I was trying to

sleep.

HUSBAND:

And I was lucky if I got once a month after that, after the pregnancy.

JUDGE:

Once a month?!

HUSBAND:

I was lucky if I got that much after she have birth.

WIFE:

Every night. Going through the groping, and begging him to stop, telling him to

stop, screaming at him to stop.

JUDGE:

Tell me something. He says it got reduced to once a month. What happened?

WIFE:

Well, basically, when he was doing that to me, night after night, I didn’t feel

like I needed to give myself to him. He was already getting it in the middle of

the night.

JUDGE:

So how long did this once a month continue? For six months after the baby was

born? For another two years? Another four years?

HUSBAND:

We really didn’t try to do something until probably two months after she had

her C-section because she had to heal and all of that, and went on for about

two years.

JUDGE:

Two years it continued like that?

HUSBAND:

Oh, yeah, and, you know, kept shaking hands with the unemployed. Had to do what

I had to do. Didn’t go out and cheat on her.

JUDGE:

Shaking hands with what?

HUSBAND:

The unemployed. Took care of myself.

JUDGE:

Ohhh! You mean like pleasing yourself?

HUSBAND:

Exactly.

JUDGE:

Whew! OK, took me awhile, but I got it.

HUSBAND:

You know, I had to take care of my needs and I wasn’t getting it from my

spouse.

WIFE:

What about my needs, Mark?

As the discussion went on, the wife mentioned

that she had faked orgasms “to get him off of me.”

Welcome to “Smut

Court.”

In the end, Ephraim

managed to remember that there was a property issue before her, and ordered the

husband to deliver the bunk beds to his wife’s present abode within 48 hours.

None of the dialogue relating to

what went on in the couple’s bedroom would have been admissible at any stage of

a dissolution of marriage proceeding in California,

which instituted a no-fault system eight years before Ephriam became a lawyer.

Now, every state has some form of a no-fault scheme.

Even if it is assumed that Ephraim is portraying

a judge in a jurisdiction that still has a partial “fault” system, there would

still be no conceivable relevance of sexual behavior to the issue of who gets

the bunk beds.

Ephraim, as a seasoned attorney, surely realizes

the lack of legal significance of the raunchy matter she not only listens to,

but elicits while playacting a judge. She must know that she is not

participating in anything resembling a faithful depiction of “divorce court”

proceedings.

She cannot lack awareness that there are those

who assume she’s actually a judge. Indeed, a Los

Angeles Times story on an

awards dinner identified her as “Judge Mablean Ephraim.” Her e-mail address

starts with “judgemablean.”

Yet, there she is on television, Monday through

Friday, purporting to conduct proceedings that create grossly false impressions

of what transpires in courtrooms.

Ephriam’s portrayal of a judge

on a show that implies that actual proceedings are being shown cannot have any

effect other than to convey that her conduct is representative of judicial

deportment. Given that Ephriam is a woman and a black, is that conduct not apt

to reflect adversely on black women judges, in particular?

I talked with two appellate justices who are

female and black.

Court of Appeal Presiding Justice Vaino Spencer

of this district’s Div. One told me she’s “caught glimpses” of current TV

courtroom depictions, and characterized them as “terrible.” With respect to Ephriam’s

portrayal of a jurist, she said:

“I would rather think that all of our judges, especially

women judges, would be concerned.”

Candace Cooper, presiding justice of Div. Eight,

remarked that courtroom simulation shows, in general, are “very unrealistic,”

but dismissed them as “purely entertainment.” She added that she assumes the

public knows that TV court sessions are “all just a show.”

With respect to Ephriam, the jurist related:

“When she’s in the community, she’s mobbed.

She’s a celebrity.”

Then, reflecting on how people react when they

encounter Ephriam, she acknowledged that “maybe they do think it’s real.”

As to Ephriam’s performance as a TV judge,

Cooper said:

“I

know she’s got a different bearing on the bench than real judges do.”

Gilbert C. Alston,

a retired Los Angeles Superior Court judge, who is black, said of the depiction

of black judges on television:

“It’s a minstrel mentality. It’s disappointing.

It’s embarrassing.”

He commented that “the image which is being

pandered to is hopefully one that is dying a deserved death,” a death which,

Alston said, “should be hastened rather than retarded.”

Nonetheless, he defended Ephriam’s role on

“Divorce Court,” saying: “It pays well in comparison to what a solo

practitioner can earn.”

Alston observed that the producers of such shows

want “laughs and entertainment” and that “you got to do what the producers

want.” He said of Ephriam: “I’m sure she tones it down from what they would

like.”

When he was on the bench, Alston related,

Ephraim appeared before him as a lawyer and displayed competency.

Phone calls to Ephriam at her law office were

not returned.

Ephriam is often referred to within the legal

community as Mablean Paxton. That was her name when she entered law practice.

On Jan. 1, 1981, she sued for a dissolution of her 23-year marriage to Cassuis

L. Paxton, a drug rehabilitation counselor, but continued using the name Paxton

well into the 1990s.

Copyright 2003, Metropolitan News Company

MetNews Main Page Perspectives

Columns

![]()