Metropolitan News-Enterprise

Tuesday, May 7, 2002

Page 9

Perspectives (Column)

An Open Letter to District Attorney Steve Cooley

By ROGER M. GRACE

Hon. Steve Cooley

District Attorney

Criminal Courts Building

Los Angeles

Dear Mr. Cooley:

These words appear on

the Office of Los Angeles County District Attorney website:

“Those who are charged

with enforcing the laws of the State of California must themselves scrupulously obey the law. They

must lead by example, and that example must be based on principles of honesty,

integrity, credibility and accountability.”

I agree with those

words. Up until last Thursday, I would have thought that you did.

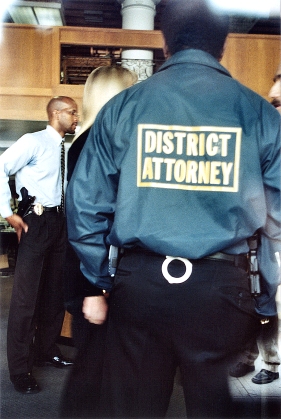

But last Thursday,

investigators from your office—acting with your knowledge and approval—invaded

our newspaper office like storm troopers, ejected our staff from the premises,

and began touring and diagramming the rooms, ascribing a number to each, in

preparation for an office-wide search. Our operations were halted for three

hours.

That conduct was

unlawful. You and your troops failed to “obey the law.” And liability on your

part exists, as I’ll discuss in a moment.

What is worse than the

intrusion itself, however, is that you, personally, as well as members of your

staff, proceeded to rationalize what had happened, abandoning the duty to

display “honesty, integrity, credibility and accountability,” and publicly

lying.

You lied that we had

promised cooperation if presented with a court document. You lied that there

was no intention on the part of your office to search our newsroom.

The first lie

was that we promised cooperation if a legal document—implying any legal

document—were served. That is false.

My wife and

co-publisher, Jo-Ann W. Grace, had talked two to three weeks earlier with an

investigator from your office, Kimberly Riddle. The investigator wanted

documents showing what law firm had placed a notice of an intent to circulate a

recall petition in South

Gate.

Jo-Ann offered to confirm the identity of the law firm if Riddle already knew

it, and volunteered that we would provide the documents in response to a

“subpoena.” The pledge to honor a subpoena was repeated by her in a subsequent

conversation with your press officer, Sandi Gibbons. And indeed, if a subpoena

had been sent to us, there would have been prompt compliance. However, Jo-Ann

never promised, expressly or impliedly, to be cooperative if you resorted to

the rash, bizarre, and outrageous tactic of commissioning the service of a

warrant for the search of our entire premises. No mention was ever made of the

prospect of your office pulling such a bonehead maneuver.

I do realize that your

office did not anticipate our raising a fuss when the warrant was served, and,

to the contrary, envisioned the materials being turned over with a smile. That

was a blunder. To journalists, occurrences of newspaper offices being searched—which,

fortunately, are quite rare—are abhorrent. A subpoena for business records is

one thing; searching a newspaper office, and potentially seeing unpublished

information and notes revealing the identities of confidential news sources, is

quite another. The service of a warrant for the search of our newspaper office

was an extreme and bellicose act which only a naïve dolt would expect to draw

cheerful cooperation. But I do acknowledge that such was the expectation of

those in your office.

Once we balked, however,

and the intention was formed to proceed with the search, the clearly manifested

intention was to search the entire premises.

This brings us to the second

lie: that a search of the newsroom was not contemplated.

That’s belied by the

facts.

The warrant you secured,

the warrant that dictated the breadth of the search if your supposition of

acquiescence proved errant, did not exclude the newsroom. It said:

“The search is to

include all rooms, safes, locked boxes, files, desks and other parts therein,

the surrounding grounds, vehicles, storage areas, trash containers and

outbuildings of any kind located thereon; any containers including all purses

and wallets found in the care/custody and/or control of ADVERTISEMENT,

ACCOUNTS RECEIVABLE, EDITING, and/or ANY OFFICE WHICH CAN PROVIDE INFORMATION

ON ALBRIGHT, YEE AND SCHMIDT PLACING PUBLICATIONS ON RECALL OF SOUTH GATE CITY

COUNCIL MEMBERS.”

Do you see the word

“EDITING” there?

Utterances that

morning—one of which was in your presence and not contradicted by you—were to

the effect that the newsroom was not off limits to the searchers.

Reviewing the events of

Thursday morning…it was shortly before 9 a.m. when my wife and I were contacted at home by

the public notice supervisor, Pamela Putnam, and told of the search warrant. As

I was talking with Pam, Jo-Ann imparted to me her supposition that the

supervisor had misconstrued the document and that it was merely a subpoena. I

asked Pam to read the heading on the document. She read it aloud. It was a

search warrant.

I asked that she convey

to the two investigators that they would have to search. (By the way—and this

is a relatively minor matter—your press release later in the day quoted you as

saying: “[E]ditor and co-publisher, Roger M. Grace refused to cooperate with a

lawful search warrant.” Putting aside for the moment whether the warrant was

“lawful,” there was no “refusal to cooperate.” A search warrant does not order

a person in possession of enumerated articles to surrender them; it authorizes

a search for such articles. In no way was execution of the warrant impeded by

me or anyone acting pursuant to my instructions. Can you grasp that

distinction?)

Pam phoned back. One of

the investigators wanted to talk to me. I spoke to him in not-so-gentle terms

(employing a particular vulgarism I am not prone to use and find repulsive),

imparting that we had offered to produce the records in response to a subpoena,

but would not cooperate with a search warrant.

Jo-Ann and I arrived at

the office about a half hour later. Our staff was on the sidewalk outside the

building, having been ordered by your investigators to go outside and not to

wander. These are Gestapo tactics.

And herein lies the

major illegality in the conduct of your office. The exclusion of the staff from

the premises, inevitably entailing a delay in newspaper production, was not

authorized by the search warrant and constituted a blatantly impermissible

governmental stoppage of journalistic operations.

The Los Angeles Times,

in its editorial Saturday, put it well in observing: “Cooley’s invasion of the

Metropolitan News evokes images from countries where newspapers either tow the

government’s line or find their offices padlocked and their reporters jailed.”

My wife and I waved at

the staff as we drove past our office at 210 S. Spring Street, turning into a

garage south of our building, driving through it, crossing an alley, and

turning into our parking lot. We entered the building from the rear, and were

greeted by a cadre of investigators. Over the next several minutes, they sought

to persuade us to surrender the materials. One of them told me that in light of

the size of the premises (approximately 30,000 square feet), it would take two

to three days to search the “entire” office. We declined to provide documents

in response to the search warrant—which we did not read (what was the

point?)—and were, as the others, ejected.

Just as you were naïve

in thinking we would accommodate a search warrant, I was naïve in supposing you

would not countenance a search of a newsroom, and that what was unfolding was

without your knowledge. I wanted to talk to you. I couldn’t phone from my

office; I had been barred from it. An employee offered to let me use her cell

phone, but I did not want to converse with you with the background noise of

cars whooshing by. I decided to drive home and phone from there.

Driving home, I

formulated a battle plan: 1.) talk with you and attempt to cause you to listen

to reason and call off the search; 2.) if that effort proved unsuccessful, bat

out on my home computer a petition to be filed in the Court of Appeal for a

“hot” (emergency) writ; 3.) summon the staff to my home and, using my computer

and Jo-Ann’s, proceed to put together some semblance of a journalistic product

and—if issuance of a writ did not intervene, causing our readmission to our

office—have the “newspaper” run-off at Kinko’s on 81/2-by-11 sheets and stuffed

into our news racks to avoid missing an issue.

While I was en route

home, Jo-Ann was invited back into our own building. Assistant District

Attorney Peter Bozanich and Deputy District Attorney David Guthman wanted to

speak with her by telephone. They talked. The impasse remained.

From home, I got you on the

line. You put Bozanich and Guthman on the speaker phone with you.

You pointed out (as your

investigators did at our office) that a subpoena was not available to your

office because a case had not yet been filed, and that no means of compelling

production other than a search warrant existed. I gathered that you expected

that to be the end of the matter. It wasn’t.

I extemporaneously

grappled for an alternative means of your gaining access to the documents. You

had no interest in compromising. You saw no need to. “We have a search

warrant,” you said flatly.

Your theme was that

there would be no search, no inconvenience, if we simply produced the

documents. The point you missed was the threat of a search was wrongful.

Perhaps you still don’t grasp that. Do you understand that investigators cannot

secure information from a person by threatening to beat him if he does not make

the disclosures? Or would you shrug your shoulders and say that all the man had

to do was simply to talk, so that the nature of the threat was immaterial?

I protested that the

only conceivable purpose in excluding our reporters and press crew from the

premises was out of spite for our non-cooperation. I mentioned that it was not

“reasonably conceivable” that reporters would have the documents in question in

their desk drawers. Guthman piped up with the comment: “We don’t know that.”

(Unbeknownst to me then

was that Jo-Ann had, in her conversation earlier with Guthman and Bozanich,

uttered a complaint similar to mine. She declared that we had agreed to honor a

subpoena; a search warrant was something quite different, potentially entailing

a search of reporters’ desks—which was legally impermissible. She was told by

Guthman that the investigators would search every drawer in the office.)

As my chat with you and

your seconds continued, Guthman made another asinine remark and I responded

that I couldn’t deal with this “idiot.” You put on a good show of loyalty to

your troops by proclaiming, with indignation, that there were no idiots in your

office. On that point, we differ.

I mentioned that Jo-Ann,

in talking to Riddle a few weeks ago, had suggested that if Riddle thought she

knew what law firm had placed the notice, she reveal this and, if she were

right, Jo-Ann would confirm the fact. You responded that you didn’t need

confirmation—“We know the name of the law firm,” you told me—and said that what

you needed was tangible evidence.

At that point, I

mentioned that if you were not seeking to ascertain from documents in our

possession the law firm’s identity, we might be able to work matters out. You

were not interested in pursuing any compromise. You simply wanted the papers

turned over in response to the search warrant.

You left to return to a

meeting. Guthman made another stupid remark, and I suggested it would be more

productive if the speaker phone were turned off and I talked solely to

Bozanich. It did turn out to be productive. Bozanich advised me that the law

firm’s name was mentioned in the search warrant. I did not have a copy before

me, nor did he. He said the firm was “Aldrich, Yee and Somebody.” I advised him

that if that proved correct, we would probably turn over the documents on the

basis of having no privacy interest of a customer to protect. I conferred by

phone with Jo-Ann; it turned out that Bozanich had the name almost right—it was

Albright, Yee & Schmit; Jo-Ann and I were in agreement that the documents

should be provided, and, as I drove back to the office, they were.

As Sandi Gibbons

recounted the events to our associate editor, Robert Greene, I was belligerent;

everyone was ousted from the premises; Jo-Ann arrived, and cheerfully turned

over the documents.

You were quoted in your

Thursday press release as saying this:

“[W]hen investigators

arrived Thursday morning, editor and co-publisher, Roger M. Grace refused to

cooperate with a lawful search warrant. A short time later, however,

co-publisher Jo-Ann W. Grace fully cooperated with the investigators and gave

them the requested documents.”

You probably think that

this favorably portrays Jo-Ann as the “good guy.” It doesn’t. It’s a false and

defamatory depiction, casting her in the light of an airheaded publisher who

would turn over, blithely, anything government asked for; it implies that she

was oblivious to the affront to the First Amendment inherent in the search

warrant.

When we learned on

Thursday morning that a search warrant had been served, Jo-Ann found this as

repulsive as I did. She expressly imparted to Bozanich and Guthman her view

that a search of reporters’ desks would be constitutionally impermissible.

Production was made,

through our joint decision, for the simple reason that what was sought were

business records, not journalistic materials, and there was no need to protect

the identity of our customer because the identity was already known to you.

The false recitation of

facts by you would tend to demean Jo-Ann in the eyes of colleagues in the

newspaper profession. Have you ever heard the word “libel”?

Let’s look at the law

relating to searches of newsrooms—something you should have done before sending

your goon squad to seize possession of our office.

In 1978, the U.S.

Supreme Court held in Zurcher v. Stanford Daily, 436 U.S. 547, that a search of a

newsroom is not precluded by the First Amendment and that the search need not

be preceded by a refusal to honor a subpoena. The court said at 565-66:

“[T]he prior cases do no

more than insist that the courts apply the warrant requirements with particular

exactitude when First Amendment interests would be endangered by the search. As

we see it, no more than this is required where the warrant requested is for the

seizure of criminal evidence reasonably believed to be on the premises occupied

by a newspaper. Properly administered, the preconditions for a warrant—probable

cause, specificity with respect to the place to be searched and the things to

be seized, and overall reasonableness—should afford sufficient protection

against the harms that are assertedly threatened by warrants for searching

newspaper offices.

“There is no reason to

believe…that magistrates cannot guard against searches of the type, scope, and

intrusiveness that would actually interfere with the timely publication of a

newspaper. Nor, if the requirements of specificity and reasonableness are

properly applied, policed, and observed, will there be any occasion or

opportunity for officers to rummage at large in newspaper files….”

The decision was widely

criticized as contravening the public interest by converting newsrooms into

hunting grounds for government investigators.

California responded that same

year by adding a provision to Penal Code §1524, which is now para. (g). It

provides: “No warrant shall issue for any item or items described in Section

1070 of the Evidence Code.” The Evidence Code section shields journalists from

contempt adjudications for refusing to disclose confidential news sources or

“any unpublished information obtained or prepared in gathering, receiving or

processing of information for communication to the public.”

I’ve read comments over

the last few days suggesting that §1524 might have applied to the documents in

our possession relating to the placement of the three recall petition notices.

Maybe I’m wrong, but I think the purpose of Evidence Code §1070, as well as the

state constitutional provision that mirrors it, is solely to protect materials

gathered for journalistic purposes (as well as allowing reporters to

safeguard sources), and not to protect purely business records.

In any event, Congress

also acted to limit the effect of Zurcher, enacting the Privacy

Protection Act of 1980. It provided in 42 U.S.C. § 2000aa that it is “unlawful

for a government officer or employee, in connection with the investigation or

prosecution of a criminal offense, to search for or seize” work products or

“documentary materials, other than work product materials, possessed by a

person in connection with a purpose to disseminate to the public a newspaper,

book, broadcast, or other similar form of public communication, in or affecting

interstate or foreign commerce.” Exceptions are listed which do not come into

play here.

The statute applies. The

materials sought by the DA’s investigators were in the possession of persons

“in connection with a purpose to disseminate to the public a newspaper.” The

MetNews is engaged in interstate commerce by virtue of its use of Associated

Press stories from around the nation. Lorain Journal Co. v. U. S. (1951)

342 U.S. 143, 152; Page v. Work (C.A.9 1961) 290 F.2d 323, 328; N.L.R.B.

v. Herald Publishing Co. of Bellflower (C.A.9 1956) 239 F.2d 410, 411

(C.A.9 1956); McComb v. Dessau (D.C.Cal. 1950) 89 F.Supp. 295, 297. It

is also engaged in interstate commerce based on its regular purchases of

newsprint and other supplies from sources outside of California and having a few

out-of-state subscribers.

A cause of action for

damages against officials breaching that section lies under §2000aa-6. That

provision denies governmental immunity to anyone other than a judicial officer.

(Are you paying attention, Steve? This means you.)

The search warrant was

unlawful. Liability lies.

Even under Zurcher,

infirmities would arise.

That decision requires

“specificity with respect to the place to be searched and the things to be

seized, and overall reasonableness.” There was specificity as to what was to be

seized; in that respect, it was, as you said in your press release, a “focused

and narrow search.” However, there was no specificity or narrowness with

respect to “the place to be searched.” The warrant permitted searches anywhere

in the office, and prying into any container including purses and wallets. That

exceeded the bounds of reasonableness.

Too, under Zurcher,

a magistrate is confined to authorizing newsroom searches which are not “of the

type, scope, and intrusiveness that would actually interfere with the timely

publication of a newspaper.” It follows that there may not be interference with

the timely publication of a newspaper in the implementation of the search.

Your invasion force

ejected our entire staff from our building. They were outside for three hours

(except Jo-Ann, who was allowed to re-enter). You had actual awareness of this.

This did interfere with the timely publication of our afternoon daily, the Los

Angeles Bulletin, which was printed three hours late. As of the time the

ejectment took place, there was the prospect of our newspaper office being shut

down for two or three days.

This was not

constitutionally permissible. This was a blatant affront to our First Amendment

rights, in the extreme. Liability lies under 42 U.S.C. 1983 for a deprivation

of federal constitutional rights.

Perhaps we were too

conciliatory, and should have sought a hot writ on the grounds that the warrant

was invalid and our exclusion from the office unlawful—a writ I suspect would

have been granted—and refused to surrender the documents until such time as

charges were filed against the suspects and a subpoena was served on us.

Maybe so.

Anyway, we didn’t follow

that course.

The question is: what

should we do now?

I have received calls

from friends advising: “Sue the bastards.” Two press associations have pledged

legal help to us.

Instituting an action

against you seems tempting.

To avert that, I ask

that no later than Friday at noon,

you do the following:

1. Issue an unqualified

public apology to us;

2. Publicly acknowledge

that your press release of May 4 contained inaccurate statements;

3. Require that every

attorney and investigator in your office—including you—attend an intensive

training session of at least two hours’ duration on avoidance of First

Amendment affronts; and

4. Secure and proffer to

us funds compensating us for the salaries of employees for the three-hour

period when they were idle on Thursday and for all over-time paid that day,

which totals approximately $3,000.

Act wisely. You didn’t

last Thursday.

Copyright 2002, Metropolitan News CompanyMetNews Main Page Perspectives

Columns

![]()