Page 1

Ninth Circuit:

Yoga Instruction Is Protected Speech Under First Amendment

Opinion Says Yogis Are Entitled to Preliminary Injunction Against Enforcement of Local Ordinance Targeting Practice in Public Shoreline Parks, Saying Plaintiffs Are Likely to Succeed on Constitutional Claim

By Kimber Cooley, associate editor

|

|

|

|

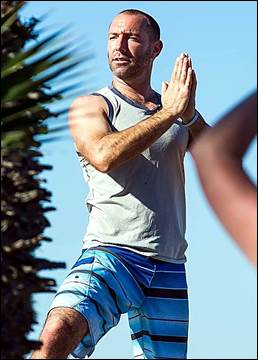

STEVEN HUBBARD |

AMY BAACK |

|

plaintiffs |

|

The Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals held yesterday that two instructors challenging a San Diego ordinance prohibiting holding yoga classes with more than three students in attendance at any of the municipality’s shoreline parks or beaches are entitled to a preliminary injunction against the enforcement of the section as applied to them, saying that training in the ancient practice is protected speech under the First Amendment.

Yesterday’s opinion reverses a decision by District Court Judge Cathy Ann Bencivengo of the Southern District of California who denied the injunctive relief after finding that the plaintiffs had failed to “establish…that the activity of teaching a yoga class is…protected speech under the First Amendment.”

At issue is an ordinance, adopted last year, which amended the city’s municipal code to define teaching yoga as a “non-expressive activity” and to prohibit the offering of fee- or donation-based services in shoreline parks or on beaches without permission from local officials. The law, San Diego Municipal Code §63.0102(c)(14), specifically defines prohibited “services” to include yoga classes.

Sec. 63.0102(c)(15) further provides that, except for authorized “expressive” activities, “it is unlawful to set up, maintain, or give any exhibition, show, performance, lecture, concert, place of amusement, or concert hall without the consent of the City Manager,” even if the events are offered free of charge.

Free Yoga Classes

Challenging the ordinance are Steven Hubbard and Amy Baack who each offered free yoga classes in San Diego shoreline parks before the adoption of the new law. They filed a complaint against the city on June 3 of last year, asserting facial and as-applied First Amendment claims under 42 U.S.C. §1983.

In their operative pleading, they allege:

“Plaintiffs are yoga instructors who have taught free and optional donation-based yoga classes in City parks for many years.

“Amy Baack stopped teaching these outdoor classes in May 2024 as a result of being threatened by park rangers with citations, and ultimately decided to move out of San Diego in part due to this infringement on her civil liberties.

“Steven Hubbard has stopped teaching outdoor classes due to being issued such citations and instead now streams them live on YouTube from his home….Some students choose to show up at the same time and place as they always have in a City park to follow along. Yet, City park rangers have continued issuing citations to Hubbard, now for teaching yoga on YouTube from his home, because it may be viewed in a City park.”

On July 1, the plaintiffs filed a motion for a preliminary injunction. Bencivengo concluded that Hubbard and Baack had not demonstrated the likelihood of success on the merits of their claims required for the requested relief, saying:

“To the extent that it goes beyond directing or leading poses to discussing potentially the philosophy of yoga, that is an incidental effect on speech.”

The judge also found the ordinance to be “content-neutral” and the restrictions to be appropriate time, place, and manner restrictions.

In an opinion, authored by Circuit Judge Holly A. Thomas and joined in by Chief Judge Mary H. Murguia and Circuit Judge Gabriel P. Sanchez, the court reversed the denial. Thomas wrote:

“We…remand with instructions to enter a preliminary injunction in favor of Hubbard and Baack on their as-applied challenge. Because the record is underdeveloped with respect to Hubbard and Baack’s facial challenge to the City’s prohibition, we do not address that aspect of their claim.”

Preliminary Injunctive Relief

Thomas said that, to obtain a preliminary injunction, plaintiffs must make a clear showing that they are likely to succeed on the merits of their claims, are likely to suffer irreparable harm without the emergency remedy, and the balance of equities tip in favor of the relief, which is in the public interest.

Turning to the likelihood of success, the jurist explained that the court must conduct a three-part analysis—first, it must decide whether the speech is constitutionally protected, then it must identify the nature of the forum, and lastly, it will assess whether the justifications for the regulation withstand the appropriate level of scrutiny.

Addressing the first step, she wrote:

“The practice and philosophy of yoga ‘date back thousands of years,’ deriving ‘from ancient Hindu scriptures.’…The practice of yoga ‘teaches students to attain spiritual fulfillment through control of the mind and body.’…A person who teaches yoga is communicating and disseminating information about this philosophy and practice through speech and expressive movements.”

She continued:

“During their classes, Hubbard and Baack raise ‘an idea or philosophy’ for their students to ‘reflect on throughout class.’ Hubbard and Baack rely on ‘foundational yoga texts…that instruct yogis on how to live a better[,] more fulfilled life.’…Hubbard and Baack also teach their students to practice mindfulness through poses and breathing exercises.”

Noting that “the First Amendment’s protections for speech encompass situations” where a teacher’s “speech” passes on “specific skills” to students, she said “[w]e easily dispose of this first step of our analysis: the First Amendment protects teaching yoga” and “the Ordinance…plainly implicates Hubbard and Baack’s First Amendment right[s].”

Public Forum

Thomas pointed out that the government may impose reasonable restrictions on the time, place, and manner of protected speech even in a public forum, and the parties do not dispute that the parks at issue qualify as such a space, but said that content-based laws targeting speech based on its communicative nature are presumptively unconstitutional and will be upheld only if they survive strict scrutiny.

Reasoning that “the content-based nature of the Ordinance” is “obvious,” she remarked:

“While the Ordinance excludes ‘expressive activity’ from [its] prohibition, it specifically states that ‘[e]xpressive activity does not include…teaching yoga.’…This is the very definition of a content-based restriction on speech.”

Pointing out that the City conceded at oral argument that the regulation allows for teaching subjects such as tai chi and performing Shakespeare productions, she rejected the defendant’s contention that the ordinance is content-neutral because it “furthers the…substantial government interest of preserving…parks and beaches for the public.” Thomas declared:

“Because the Ordinance is not content neutral, it does not qualify as a valid time, place, and manner restriction, and is presumptively unconstitutional.”

Strict Scrutiny

Applying strict scrutiny, she wrote:

“The Ordinance fails this analysis. To defend its prohibition on teaching yoga, the City cites its ‘important governmental interests’ in ‘protecting the enjoyment and safety of the public in the use of’ its shoreline parks…. Although public safety is a compelling interest…—and even assuming for the sake of argument that public enjoyment is as well—the City has provided no explanation as to how teaching yoga would lead to harmful consequences to these interests, or even what those consequences might be. The City therefore cannot demonstrate that its prohibition against teaching yoga is narrowly tailored to meet its interests.”

Thomas added:

“Because the City has demonstrated no plausible connection between Hubbard and Baack teaching yoga and any threat to public safety and enjoyment in the City’s shoreline parks, the Ordinance fails strict scrutiny.”

Addressing the remaining factors relevant to the preliminary injunction analysis, she noted that irreparable harm is easily established in this context because the party seeking the injunction must only demonstrate a colorable First Amendment claim.

Explaining that the balance of equities analysis and the public interest consideration “merge” when the party opposing the request is a government entity, she concluded:

“That Hubbard and Baack ‘have raised serious First Amendment questions compels a finding that…the balance of hardships tips sharply in [their] favor.’…And ‘it is always in the public interest to prevent the violation of a party’s constitutional rights.’ ”

The case is Hubbard v. City of San Diego, 24-4613.

Copyright 2025, Metropolitan News Company