Page 1

Attorney Selma Moidel Smith Dies at the Age of 106

By a MetNews Staff Writer

|

|

|

SELMA MOIDEL

SMITH |

Selma Moidel Smith—a legal practitioner, bar leader, author/editor, and composer of musical works—has died at the age of 106.

She became a lawyer in 1943 and maintained active bar status for 43 years. Smith served two terms as president of the Women Lawyers Association of Los Angeles, in 1947 and 1948, and was the group’s only honorary life member.

Until 2002, at the age off 103, she was editor of California Legal History, the journal of the California Supreme Court’s Historical Society.

Smith wrote more than 100 musical compositions. They have been played by orchestras across the nation, including the Los Angeles Lawyers Philharmonic.

She was known as a “Renaissance Woman.”

Below, there appears a eulogy delivered yesterday by her son and only surviving family member, architect/historian Mark L. Smith.

★★★★

How Lucky Am I:

A

Remembrance of My Mother, Selma Moidel Smith

By Mark L. Smith

(The writer is the son of Selma Moidel Smith who died Friday at the age of 106. The remarks were delivered yesterday at Hollywood Forever.)

|

M |

y dear, sweet, loving and beloved mother has left us, and I am aware that I have had the privilege of living in an enchanted kingdom of her making. For everyone who knew her, she was larger than life. To me, she was the most extraordinary role model that a child, adult, and now, senior citizen could have at every stage of life.

Her career in the law is well known, so it is my sad pleasure to share some thoughts from my own perspective that have not been recounted before.

The leitmotif of her life has been optimism in the face of loss. At the age of eight, she watched her father die suddenly from sepsis. Her three elder brothers each departed too young, one in a plane crash returning from World War II, one from a rare cancer, and the most recent from a sudden heart attack, 48 years ago. Second-hand, she learned about the other two child siblings of her family who had died before she was born. And only when I was applying for my first passport and would need to see my birth certificate, did she confide in me her secret sorrow that I had been born a twin, the other stillborn. (When anyone would ask if I was an only child, she would always reply, “He is all of my children.”) A corner of her soul was in perpetual mourning. Yet, despite or perhaps because of it, she had the most determined, positive, and optimistic attitude toward life. The quick self-portrait, with its cheery smile, that she kept in her desk at home says it all.

My

mother was strengthened by obstacles. Near the end of her second year of law

school at USC, she had an emergency appendectomy that kept her out of school

for a month. She told me how she brought her law books to study in the hospital

and was so weak on returning to school that teams of fellow students, men of

course, would carry her up the stairs to class. But the administrators were not

satisfied. They informed her that she could not receive credit for any of her

classes that year because she had not been in residence the required number of

hours. She enrolled in summer school and offered to challenge her classes by

examination. But they would not yield and said she would need to repeat her

entire second year. In early 1941, still during the Great Depression, this

would have been impossible for her or her family. As a result, she transferred

to the then well-regarded law school at Pacific Coast University in downtown

Los Angeles. They generously agreed to let her take her third-year classes

while, at the same time, repeating her second-year classes. Her dedication was

unmatched. On the morning of her wedding, her professor exclaimed. “Aren’t you

getting married today, Miss Moidel?” She replied,

“Oh, that isn’t until this afternoon,” and he ordered her out. She succeeded in

all of her double set of classes, at the last minute becoming the final student

to qualify for the bar exam. And she passed it the first time. On revisiting USC

for some other matter, she encountered the well-known dean of the time, William

Hale, who said, “Well, Miss Moidel, we made a

mistake.” Decades later, the law school would proudly and repeatedly claim her

as one of their distinguished alumni.

|

I |

need not recount how quickly Mother gained recognition among her colleagues, becoming president of the women lawyers in Los Angeles at the age of 27, and Western Region director of the National Association of Women Lawyers two years later. She practiced law with distinction until taking inactive status with the State Bar in 1986.

Yet, as everyone who is acquainted with my mother’s life knows, she created for herself two parallel careers—one in law, the other in music. She had studied violin at her mother’s insistence as a child, becoming concertmistress at Hollywood High School. But then, in 1953, when she began to study her true love, the piano, she began to “hear” compositions. As she described it, they would play in her head completely worked out, without effort on her part (a gift most often associated with Mozart). I later learned that, when I was about three, mother had such determination to pursue a formal education in music that she planned her class schedule at the UCLA School of Music so she could leave me at home with a babysitter, race over the Sepulveda Pass (before construction of the San Diego Freeway) in time to attend class and return before I awoke from my afternoon nap. My life has been blessed by the constant presence of her beautiful compositions. In more recent years, she asked at times what I thought of her music, and I always replied. “If you had done nothing else....” She understood that I meant this was her most lasting and unique contribution to the world, in the midst of so many others. Standing at the piano in her living room, I continue to see and hear her sitting at the keyboard. Thankfully, there are many recordings.

|

|

|

Smith is at the Washington World Conference on World Peace Through Law with Chief Justice Earl Warren, honorary conference chair, at the U.S. Supreme Court Building in 1958. |

My mother was an explorer. Alone among her family, she had the urge to travel—often privately, at other times for professional conferences. Before I was born in 1957, there was Hawaii in 1952, Bermuda in 1953, Europe in 1954, Mexico in 1955, the Caribbean in 1956—then a hiatus. Our first trip as a family was to the Sequoias when I was three. And travel resumed in earnest when she came into my bedroom one day when I was nine, announcing: “How would you like to go to Alaska?” The ensuing fifty years were marked by trips to every place on earth that interested her. At first, she took me; much later, I accompanied her. In Spain, I drove while she led the way with her fluent Spanish. In London, she attended a piano master class at the Royal College of Music for three weeks, and I arranged weekend outings to the Glyndeboume Opera and lavish country houses. Over the summers, we attended every major classical music festival in the U.S. and Europe. Frequently during the twenty years before the Covid epidemic of 2020, these would occupy the weeks between the annual conferences of the American Bar Association and National Association of Women Lawyers—at both of which she always had important duties.

And for

me, the “enchanted kingdom” of her life meant her wish to include me in all the

activities that animated her. In the course of her fifty years as a board

member and ambassador of goodwill for a cause in which she believed, the

Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania (now subsumed by Drexel University in

Philadelphia)—she brought me to meet her colleagues and contacts: Princess

Grace of Monaco, Pennsylvania senators and congressmembers, medical scientists,

and many others. At the ABA, she introduced me to her coworkers—prominent

American lawyers, judges, and justices. The same, of course, became true with

the distinguished leaders of the California Supreme Court Historical Society,

where she insisted on sharing her new friends with me.

|

M |

other’s work with the Society was part of the golden third (if not fourth) chapter of her remarkable later life. By the 1980s, she had retired from active practice and found pleasure in joining the Plato Society (then, “of UCLA”), a learning-in-retirement group organized by UCLA Extension largely for retired professionals. She pioneered a course titled “The Music of Spain,” which she repeated by popular request for eleven consecutive years. Gifts from her students adorn her home. But then, in 1996, came a fateful phone call. She had reached out to the National Association of Women Lawyers to see some revised contact information, and their president called back to ask if she would serve as liaison to the ABA Senior Lawyers Division, which had requested such a connection. She attended the next meeting of the SLD Council, was immediately taken with the group—and more importantly, they with her—and by the next year was appointed to the editorial board of their magazine. Two years later, the editor recommended her to succeed him (in what was then a decidedly male organization), and she was also elected to the SLD Council. This was all the Plato Society’s loss. To an organization that was invariably its members last professional stop, she wrote a letter in 1997 explaining that she had become too busy with outside activities to continue her membership!

The following decades were a whirlwind of quarterly meetings around the country, filled with work on publications and substantive committees. She was ultimately appointed to the honorary position of “Special Advisor” to the ABA’s Experience magazine, which she had edited. By remarkable good fortune, her latest reappointment to that position came when she was having an especially good day shortly before her death, and I was able to share the letter with her and see her gratitude at continuing to be remembered for her service.

The other stroke of good fortune that came from her ABA SLD years was that, in 2000, she had requested an article

about legal innovation in California from Professor Harry Scheiber at Berkeley

Law. In the course of his writing, she became what he later called his “best

editor ever” and, one day in 2001, immediately after completing her term as

editor, came an email from Harry asking permission to nominate her to the board

of the CSCHS. The Society became her glorious and

culminating professional home. I remember the day, at the age of 89, when she

told me she had been asked to serve as editor-in-chief of their flagship

publication, the California Legal History journal. She went on to produce

fourteen outstanding annual volumes.

|

|

|

B |

ut people might also wonder about her role simply as “mother.” She was unique. The fate that randomly assigns family members worked, in our case, a miracle of good fortune. We bonded early, not least as mother and son, but far more as friends, coworkers, mutual supporters, and, ultimately, souls devoted to one another. I flourished in the glow of her constant encouragement and praise and approval. She was, of course, the keeper of the memories of my childhood. If I felt burdened by work, she would remind me of my words to her as a child when she had felt the same: “You don’t do what you have to, you do what you can.” She continued to laugh at my complaining as a child, when I had finished a certain work of art: “It looks like a child did it, and I don’t know why!” When asked more recently what I was like as a child, she replied with her usual wit: “Smaller.”

She was the ideal support for an emerging adult. She insisted I pursue my own choice of career, despite others expecting me to follow hers. When I came home at Thanksgiving from my first year at college to say I was tired of being in school (I was only a Regents Scholar at Berkeley) and wanted to take time off to work in my chosen field, she listened.

How many parents would respond at that moment, “I’ve always trusted your judgment, and you should do what seems right for you.” And she helped me to find that first (and only) job by driving me as I visited 45 offices in two days, at last finding a place in the office that would eventually become, to this day, my own. And, of course, she then subtly suggested that I reenter the university world, first through correspondence courses at Cal, then by transferring to UCLA, where (simultaneously with my office work) I graduated on schedule. It was she who ran from office to office on campus to make sure I would graduate as a member of Phi Beta Kappa, when it seemed I had been overlooked because of my unusual history. Later, although our professions were in different fields, she imbued me with the sense of professional responsibility and loyalty to ideals that is embodied in service to one’s clients.

Mother’s multifaceted career was also surely the model that would enable, if not dictate, my own unrelated careers as architect and historian. She wholeheartedly supported my midlife pursuit of a doctorate in history at UCLA and celebrated the appearance of my first book when she was already 100 years of age.

Now that my life will be permanently divided, like “B.C. and A.D.,” into the periods with and after my mother, it was my bittersweet joy to be able to conclude the final touch on my forthcoming book “with her” on the day before she passed away.

|

|

|

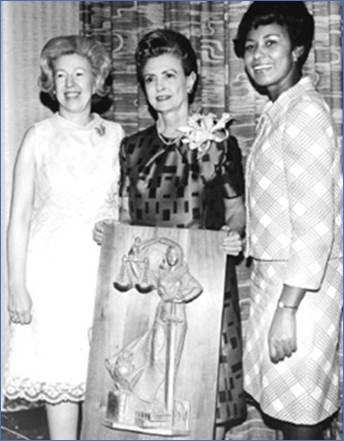

Smith is seen at the Women Lawyers Association of Los Angeles Law Day Luncheon on April 27, 1968, with, to the right, Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Kathleen Parker, since deceased, and then-Assembly member Yvonne Brathwaite, who became a member of Congress and a member of the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors. |

|

M |

other inspired with her optimism and adventurous spirit. To give but one seemingly trivial example: A dozen years ago, the building in which my office was located had become rundown, and it was clear that a move was needed. I had remodeled the office decades earlier, and she had helped by picking out one of those little artificial trees, of the type then popular, for the reception room. I brought her to the old office one evening to get “her blessing” as it were for the move, and she agreed. She said, “Yes, Markie, it’s time to take our little tree someplace new.” And I loved her for it, and to this day, I embrace her for her spirit. In her mid-nineties, she was ready for a new adventure! And up until Covid, she would love it when I brought her to visit at the new office, and she would sit in the conference room with our little tree.

She once said to me that every headstone should be engraved with the words, “Unfinished Business.” And yet I can report with wonder that this cannot be said of her. She had no regrets. There could always have been more, but there was nothing she felt she had failed to do. She enjoyed strong friendships and extended family, traveled everywhere she could have wished, saw her own accomplishments in every field. Not once did I hear her say she wished for something she had not achieved.

She was practical about matters of life and death. She would say the only immutables in life are that “we are blind and mortal.” In 2009, we went together to see the new movie “Marley and Me” about the life of a dog. On leaving the theater, she and two young women struck up a conversation and they asked how she liked the movie. She said it was wonderful, that she had loved it. They said, “But it was so sad, in the end the dog dies.” And my mother replied, “But that’s what life is. If you have a dog, you love the dog, but you know the dog will die. That’s what it means to have a dog.” And, of course, she was talking about more than dogs.

Her one

intimation about mortality was her insistence that anything done in a person’s

honor after the person was gone had no value. “What matters is what you do for

someone when they are there to know it,” she said. For that reason, I began to

insist there should be a celebration of her, and of her music and her career,

that eventually took the form of the 95th birthday concert she agreed to have

in 2014. It was at this event that the renaming in her honor of the Society’s

student writing competition (which she had created and run) was announced. The

event was, as her dear friend [then-California Supreme Court] Justice Kathryn

Werdegar said on that occasion, “the hottest ticket in town.” It can be viewed

on YouTube.

|

H |

er music also required a forward-looking celebration. When Mother and I were discussing the eventual placing of her papers in an appropriate research library, I mentioned her music manuscripts. She nearly wailed, “I don’t want my music to be buried alive.” And, with time. I found a solution at our joint alma mater. In late 2020, I contacted the School of Music at UCLA, to ask if it might be possible for them to establish a recital series in my mother’s name that would include, in part, performances of her own music. They were receptive but said they would first need to hear some of her music. I directed them to the website I had created for her, and they came back to say they would be happy to host such a program. The result is the annual, perpetual, Selma Moidel Smith Recital. When I asked her consent before making the final arrangements, my mother’s only response was, “Bless you, son.” My continuing reward has been to witness my mother’s delight as I would play and replay for her the YouTube videos of each of the first five annual recitals. And thanks to her admonition, I too have no regrets in this regard.

Mother remained an inspiration throughout her last years. Shortly before her brief final illness, her legs would not hold her, so I would seat her on a little steno-type chair and roll her from room to room. Once, when I gathered speed, she exclaimed, “This is fun!” And in the hospital, her spirit was never downcast, but always cheerful. She retained her fighting spirit. One night, when she was lying asleep in the dark, a nurse came in to check her and turned on all the bright lights. Waking instantly, my mother shot out, “Mark, how dare you!”—since, to her. I had become the only constant that surrounded her.

Returning home for her final month, and confined for the first time to bed, she was greatly diminished. I discovered that, stripped to her bare essence, that essence consisted solely of love. Her words became few. She would look up at me and say, “I love you,” or “My love,” and I would return the love with words and kisses a thousandfold as she would smile and go back to sleep.

When she lay still, about to take her last breath, I put my cheek to hers and said, “Sweet dreams, my princess. You are my jewel, my soul, my heart, and my gem. I wish you every blessing.” And soon, the nurse said she was gone, I cried out. “I was expecting lightening and thunder, and there is only quiet.” Surely the world should be diminished by the loss of such a person. Forever in my own heart, and hopefully in the hearts of the people who knew her well, she will continue to glow with love.

Copyright 2025, Metropolitan News Company