Page 3

Ninth Circuit:

SEC May Condition Settlement on Non-Denial of Fault

Free-Speech Facial Challenge to Rule Fails; Opinion Says Policy Entails Permissible Waiver

By a MetNews Staff Writer

|

|

|

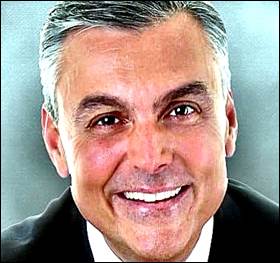

RAYMOND J. LUCIA petitioner |

The Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals held yesterday that a Securities and Exchange Commission rule requiring that parties who wish to settle civil actions with the agency refrain from denying the allegations against them—or face reinstitution of enforcement proceedings—does not, on its face, violate the First Amendment.

Saying that the so-called “no deny” policy effectively requires the settling party to waive constitutional rights, much like a criminal defendant agrees to do in entering a guilty plea, the court declared that the rule, as written, survives constitutional scrutiny.

Circuit Judge Daniel Aaron Bress authored yesterday’s opinion, saying:

“The law has long regarded the voluntary relinquishment of constitutional rights as permissible, so long as appropriate safeguards are attached. And when we apply the Supreme Court’s and our court’s framework for the voluntary waiver of rights, we conclude that [the rule] is not facially invalid under the First Amendment, even though legitimate First Amendment concerns could well arise in a more particularized type of challenge.”

He added:

“The SEC assures us in its briefing that ‘[d]efendants who enter into settlements with the Commission remain free to speak about the Commission, enforcement actions, and a host of other topics so long as they do not publicly deny the Commission’s allegations.’ Defendants who have settled with the SEC should therefore understand that they have full latitude in this regard, including when it comes to criticizing the SEC. At the same time, we question how easy the SEC’s line will be to police in practice….”

No-Deny Rule

At issue is 17 C.F.R. §202.5(e), which provides:

“The Commission has adopted the policy that in any civil lawsuit brought by it or in any administrative proceeding…, it is important to avoid creating…an impression that a decree is being entered or a sanction imposed, when the conduct alleged did not, in fact, occur…..[I]t hereby announces its policy not to permit a [party] to consent to a judgment or order that imposes a sanction while denying the allegations in the complaint or order for proceedings.”

On Oct. 30, 2018, the New Civil Liberties Alliance (“NCLA”), a public interest law firm founded in 2017, filed a petition with the SEC requesting that the agency amend §202.5(e) to eliminate the “no-deny” rule, citing First Amendment concerns. After the SEC failed to respond, the NCLA filed a renewed request in December 2023, adding individual petitioners.

In January 2024, the SEC denied the petition, providing a six-page letter explaining why it was maintaining its policy. Commissioner Hester M. Peirce, an appointee of President Donald Trump, penned a dissent to the denial, writing:

“One thing I love about this country is that Americans can and often do criticize their government….The policy of denying defendants the right to criticize publicly a settlement after it is signed is unnecessary, undermines regulatory integrity, and raises First Amendment concerns.”

Challenge to Denial

Multiple parties challenged the denial by filing a petition for review in the Ninth Circuit. One such petitioner was Raymond J. Lucia, a financial advisor based out of San Diego who rose to national prominence after he began hosting a radio show and publishing books touting an investment strategy known as “Buckets of Money.”

He settled an enforcement action against him by the SEC in 2020, after the agency accused him of omitting material information in his presentations, agreeing to a fine of $25,000 and a three-year ban from participating in the securities industry.

Bress said the court has jurisdiction to hear the matter under 15 U.S.C. §78y(a)(1), which permits “[a] person aggrieved by a final order of the Commission…[to] obtain review of the order in the United States Court of Appeals for the circuit in which he resides,” and cited Lucia as a qualified party to maintain the petition.

The jurist noted that the rule, which has been in place since 1972, has been the subject of much criticism, but remarked that “SEC Commissioner Peirce and others have challenged the wisdom of Rule 202.5(e), but the wisdom of regulatory policy lies outside our authority.” However, he said that the petition is properly before the court, writing:

“Deciding whether an agency action violates the First Amendment is, of course, very much within our authority.”

Circuit Judge Ana de Alba and Senior Circuit Judge Sidney R. Thomas joined in yesterday’s opinion.

Voluntary Accession

Bress opined that “Rule 202.5(e) is not simply a speech-restricting rule, but a rule that defendants voluntarily accede to in return for substantial benefits” and pointed out that “rights, including constitutional rights, can be waived.” He cited the 1987 U.S. Supreme Court decision of Town of Newton v. Rumery as providing the guiding principles for analyzing purported waivers of First Amendment rights.

In Rumery, the high court upheld an agreement in which a defendant released his right to bring a civil rights action under 42 U.S.C. §1983 in exchange for the prosecutor dismissing pending criminal charges against him. The decision announced that such waivers should be analyzed by considering the public policies relating to enforcement.

Applying that framework, he reasoned:

“The Rule in its purest form allows the SEC to return things to how they were before the settlement, potentially allowing the SEC to pursue its claims in court….In this sense, there is a ‘close nexus’ between ‘the specific interest the government seeks to advance in the dispute underlying the litigation involved’—proving the allegations supporting its enforcement actions—and ‘the specific right waived’—the defendant agreeing not to deny those same allegations.”

He noted that the SEC’s letter accompanying the denial indicated that because “it does not try its cases through press releases,” the rule “preserves its ability” to pursue legal action if a defendant “chooses to publicly deny the allegations.”

Justifications Considered

Considering this justification, Bress wrote:

“The absence of a policy like Rule 202.5(e) could lead the SEC to require[e] more outright admissions or settl[e] fewer cases, which may not necessarily be in the interest of civil enforcement defendants….Provided that any limitation on speech remains within proper bounds, and given the background ability to waive First Amendment rights at least to some extent, the SEC has an interest in giving defendants the option to agree to a speech restriction as part of a broader settlement agreement.”

However, the jurist took issue with the SEC asserting in the letter that the policy is necessary to promote public confidence in the SEC’s work, saying:

“[T]his rationale would be improper….A defendant who denies the SEC’s allegations may well undermine confidence in the SEC’s enforcement programs. But undermining confidence in the government is an inevitable result of our robust First Amendment protections for speech critical of the government. The SEC’s valid interest in Rule 202.5(e) is thus more mechanical: that if a defendant wants to deny the allegations, the SEC wants to be able to prove those allegations in a particular forum, i.e., in court, with the benefits and protections of the judicial process.”

Narrow Limitation

Concluding that the “relatively narrow limitation” on the settling parties’ speech does not run afoul of the First Amendment, he cautioned that “we note evidence in the record of settlement agreements” that could amount to violations, including examples where defendants purportedly agreed not to make “any public statement denying, directly or indirectly, any allegation” or “creating the impression” that a complaint is without factual basis. He wrote:

“[I]nsofar as the SEC’s settlement agreements impose greater obligations than the face of Rule 202.5(e) itself, today’s decision—which concerns the denial of a petition to amend Rule 202.5(e) itself—does not resolve whether such a settlement agreement could survive a Rumery…challenge….If defendants raise such challenges, courts should carefully consider them, mindful of the important values associated with permitting criticism of the government.”

He added:

“Nor do we decide if it would be constitutional for the facial restrictions in Rule 202.5(e) to apply in perpetuity. It stands to reason that under a Rumery analysis, the government’s interest may wane as time passes.”

The case is Powell v. U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, 24-1899.

Prior to the 2020 settlement, Lucia’s fight with the SEC went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

After Administrative Law Judge Cameron Elliot ordered that Lucia pay sanctions of $300,000 for securities violations, the defendant argued that the proceeding was invalid because the jurist had not been appointed to his position by the President, “Courts of Law,” or “Heads of Departments,” as required by the Appointments Clause of the U.S. Constitution.

In a 2018 opinion authored by Justice Elana Kagan, the high court agreed with Lucia that, as one appointed to his position by SEC staff members, Elliot “lacked constitutional authority to do his job.” The court ordered that Lucia be given a new hearing “before a properly appointed official,” and declared that such “official cannot be Judge Elliot, even if he…receives…a constitutional appointment” because “he cannot be expected” to hear the case anew.

Copyright 2025, Metropolitan News Company