Page 4

Ninth Circuit:

Nonfungible Tokens Are Goods Worthy of Trademark Shields

Opinion Says Although Maker of Popular Digital Asset Established Protectable Interests, Summary Was Judgment Improperly Granted as to Infringement Claims Against Rival

By Kimber Cooley, associate editor

|

|

|

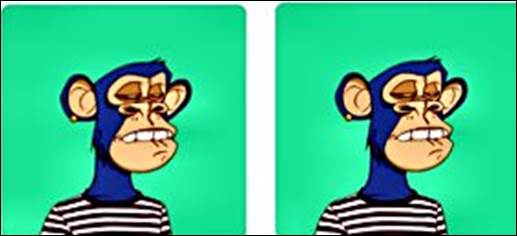

Above is a screenshot from the plaintiff’s complaint, purportedly depicting two offerings from the nonfungible token marketplace OpenSea. The left is an official Bored Ape Yacht Club asset made by the plaintiffs and the right is one created by the defendants. The Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals yesterday reversed a summary judgment against the defendant for copyright infringement, saying the plaintiff had not proven its case as a matter of law. |

Nonfungible tokens—or selections of authenticating software code associated with unique content expressions like digital artwork—are “goods” worthy of the protections afforded by the Lanham Act, which regulates the use of trademarks in commercial activity, the Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals held yesterday.

In an opinion authored by Circuit Judge Danielle J. Forrest, the court said that the relevant statutory scheme does not categorically exclude the digital assets and determined that the creator of a widely popular collection of nonfungible tokens (“NFTs”) sold under the name “Bored Ape Yacht Club” had trademark priority over the associated marks because it was the first to use them in commerce.

However, the panel said that the company was not entitled to summary judgment on its infringement and cybersquatting claims, asserted against a rival entity selling NFTs bearing nearly identical features, because it had not established that the defendants’ use was likely to cause consumer confusion as a matter of law.

Mindful of the “complexity” at issue, Forrest devoted space to explaining the newfound asset class, noting that NFTs “are primarily used for selling digital art,” which may itself not be capable of copyright protection, but transforms into “a unique asset with proprietary value” when made into a token.

She added that NFT creators “tokenize” content through a process called “minting,” whereby it is stored on a blockchain or public digital ledger that keeps track of the initial purchase and future conveyances. A so-called “smart contract,” or specialized computer program, keeps track of the minting, storage, and transfer of NFTs.

Complaint Filed

The questions surrounding NFTs arose after the Bored Ape Yacht Club (“BAYC”) creator, Yuga Labs Inc., filed a complaint against Ryder Ripps and Jeremy Cahen in 2022, asserting claims for trademark infringement and cybersquatting. In the complaint, the plaintiff alleged:

“Yuga Labs is the creator behind one of the world’s most well-known and successful Non-Fungible Token (“NFT”) collections, known as the Bored Ape Yacht Club (a.k.a. “BAYC”). The Bored Ape NFTs have earned significant attention from the media for their popularity and value, including being featured on the cover of Rolling Stone magazine and being dubbed ‘the epitome of coolness for many’ by Forbes. Bored Ape NFTs often resell for hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of dollars, and prominent celebrities are proud holders of Bored Ape NFTs. Aside from certain benefits that come with being a member of the exclusive community of Bored Ape NFT holders, much of this NFT collection’s value arises from their rarity—only 10,000 Bored Ape NFTs exist, and each is entirely unique.”

Each NFT offered by the plaintiff is associated with a unique piece of artwork depicting a cartoon primate, and the terms of sale provide that purchasers secure the rights to that particular image, royalty-free. Each BAYC NFT also doubles as a membership pass, allowing so-called “ape holders” to join an exclusive online social club.

Yuga receives a percentage of any third-party sales made after the initial purchase.

Public Criticism

In 2021, Ripps began publicly criticizing Yuga, saying the company’s ape-based artwork contained “neo-Nazi symbolism, alt-right dog whistles, and racist imagery.” In May 2022, he collaborated with Cahen to create a new collection called “Ryder Ripps Bored Ape Yacht Club” (“RR/BAYC”), purportedly to satirize Yuga’s brand.

The RR/BAYC NFTs are linked to the same ape cartoons and identification numbers as Yuga’s counterparts on some websites that offered the assets for sale. The plaintiff contends that the similarities between the defendants’ offered NFTs and its own were so striking that a company that authenticates tokens wrongly identified RR/BAYC sales as Yuga transactions.

Ripps and Cahen primarily sold their NFTs through a website they hosted, and some were also transacted through social media. Each token sold for between $100 and $200, and the defendants made more than $1.36 million by selling out the entire collection.

Yuga moved for summary judgment on its claims under the Lanham Act and the Anticybersquatting Consumer Protection Act and on counterclaims filed by the defendants. District Court Judge John F. Walter of the Central District of California granted the motion and held a bench trial on remedies.

Following the trial, Walter permanently enjoined the defendants “from marketing, promoting, or selling products or services…that use the BAYC Marks,” and awarded Yuga over $8 million for disgorgement of profits, statutory damages, attorney fees, and costs.

Yesterday’s opinion, joined in by Circuit Judge Bridget S. Bade and District Court Judge Gonzalo P. Curiel of the Southern District of California, sitting by designation, reversed the summary judgment order as to the plaintiffs’ two claims, saying:

“Yuga may ultimately prevail on these claims, but to do so it must convince a factfinder at trial.”

Definition of ‘Goods’

Forrest noted that the Lanham Act protects marks used with “any goods or services” and that the defendants argued that Yuga’s trademark claim fails because an NFT does not fall into either category.

She acknowledged that the statute does not define the terms but said that it also “does it exclude certain categories of goods and services from its protection.” The jurist pointed to a 2024 report by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office concluding that NFTs are goods covered by the act.

In arguing that NFTs are not covered, the defendants point to the 2003 U.S. Supreme Court case of Dastar Corp. v. Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp., which addressed whether the Lanham Act prohibits the unaccredited copying of a video cassette for commercial purposes. Because copyright law already protects the communicative content in the footage, the high court concluded that also affording trademark protection to the tape would be superfluous. Rejecting the analogy to the Dastar case, Forrest remarked:

“Defendants understand [the case] to mean that intangible goods, including NFTs, are ineligible for trademark protection because they are not ‘goods.’ But the Supreme Court did not adopt a bright-line rule….Rather, it recognized a distinction between the tangible good and the intangible aspects of that…good.”

The jurist continued:

“Unlike the intangible content at issue in those cases, NFTs are not contained in or even associated with tangible goods that are sold in the marketplace. NFTs exist only in the digital world, and they are associated only with digital files. NFTs are marketed and actively traded in commerce….Indeed, consumers purchase NFTs as commercial goods in online marketplaces specifically curated for NFTs.”

First to Use

Saying that “[t]here is no dispute that Yuga was the first to use the BAYC Marks in commerce,” she was similarly unpersuaded by the defendants’ assertion that the company’s use of the marks amounted to illegal sales of unregistered securities or that it gave up its trademark rights by transferring rights over the cartoon images.

Forrest said that the plaintiff’s terms of sale “unambiguously do not assign trademark rights in Yuga’s marks” and that the company “did not have to expressly carve out a grant of trademark rights to avoid conveying them.”

Turning to the question of infringement, she said that the plaintiff “must show a likelihood of consumer confusion between the Defendants’ allegedly infringing marks and Yuga’s marks” based on whether a “reasonably prudent consumer” is likely to be confused as to the origin of the good or service.

Courts apply a non-exhaustive list of factors to determine consumer confusion, and the three most important considerations in cases involving internet commerce are the similarities between the marks, the relatedness of the goods or services, and the marketing channels used to sell the products.

She opined that Walter failed to follow warnings in case law “to exercise caution” in granting summary judgment in this context, given the fact-specific nature of the analysis, by “easily” concluding that the “[d]efendants’ use of Yuga’s BAYC Marks was likely to cause confusion.”

Addressing the similarity factor, she pointed to some differences between the plaintiff’s marks and those used by the defendants, including the use of the “RR” prefix, which she said points to the origin and source of the defendants’ NFTs because it refers to the Ripps initials and “adds additional sounds… when reading the word out loud.”

The justice wrote:

“Despite the similarities between the marks at issue, the differences…are sufficient for a reasonable juror to conclude that these marks are not similar.”

Under these circumstances, she said that “the current record does not clearly signal on which side of the ledger this highly critical factor lands.”

Finding similar open questions with regard to market channels and actual confusion, she declared:

“Yuga is not entitled to prevail on its trademark infringement and cybersquatting claims at this stage because it has not proven as a matter of law that Defendants’ RR/BAYC project is likely to cause consumer confusion in the marketplace.”

The case is Yuga Labs Inc. v. Ripps, 24-879.

Copyright 2025, Metropolitan News Company