Page 1

Ninth Circuit:

Royalty Agreement Is Not Perpetual Obligation Under Law

Opinion Says Band Members’ Agreement to Divide Songwriting Revenue Has Termination Date Despite Contractual Silence Because Works Will at Some Point Fall Into Public Domain

By Kimber Cooley, associate editor

|

|

|

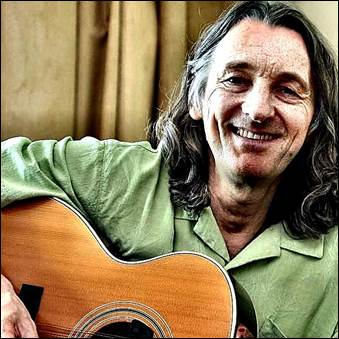

ROGER HODGSON former vocalist/songwriter |

The Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals yesterday reversed a judgment entered in favor of former rock star Roger Hodgson in a lawsuit filed by three of his former Supertramp bandmates who alleged that the frontman suddenly stopped paying them songwriting royalties in violation of an agreement, finding that the trial judge improperly ruled that Hodgson and others were entitled to unilaterally terminate the agreement after a “reasonable time.”

In yesterday’s opinion, written by Circuit Judge Kim McLane Wardlaw, the court acknowledged that California case law has established that contracts may be terminated after a reasonable time if they contain no express or implied duration, but said the royalty agreement by its nature contains a termination point: the date at which the works will cease to generate revenue because they fall into the public domain under U.S. copyright law.

At issue is a 1977 agreement entered into between the members of the iconic 1970s Supertramp band—responsible for hits such as “Give a Little Bit” and “Take the Long Way Home”—pursuant to which they agreed that Hodgson and Rick Davies, the primary writers of the music, would share publishing rights to the songs with the group’s other musicians.

Contractual Terms

Under the contract, Hodgson and Davies are entitled to receive 27% each of any income derived from the publication of certain of the group’s songs, and the remaining members—Douglas Thomson, John Helliwell, and Robert Siebenberg, together with the band’s former manager David Margereso—are due 11.5%. They agreed that Delicate Music, a sub-publishing company owned by Hodgson and Davies, would administer the payments. The parties entered into the agreement at a time when their recording contract with A&M Records precluded them from receiving other royalties relating to the sale of the records.

Delicate Music allocated the publishing royalties in accordance with the 1977 agreement until 2018, when the company suddenly ceased making payments. Thomson, Helliwell, and Siebenberg responded by filing a complaint for breach of contract against Hodgson, Davies, and Delicate Music in Los Angeles Superior Court in 2021.

After Davies removed the action to federal court, the plaintiffs settled their claims with him, leaving Hodgson and Delicate Music as the sole defendants. Thomson, Helliwell, and Siebenberg moved for summary adjudication on their claim for breach of contract and other issues, arguing that there was no genuine dispute of material fact that, under California law, the agreement is valid or that the defendants breached it.

Single Issue

In August 2023, District Court Judge André Birotte Jr. of the Central District of California granted the motion in part, reserving a single issue for trial, saying that a fact-finder must resolve the following question:

“Is (or was) Defendants’ obligation to pay Plaintiffs royalty interests (1) terminable at-will; or (2) conferred in perpetuity.”

During a six-day jury trial, both parties moved for judgment as a matter of law under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 50. In denying the motions as to the 1977 agreement, Birotte said that he had made the “judicial determination that the contract contains no express duration nor has sufficient evidence been presented that there can be an implied duration based on the surrounding circumstances.”

He declared that the only question to be presented to the jury was whether the defendants “terminated the contract at will, after a reasonable time.” Following an affirmative answer by the panel, and judgment was entered against the plaintiffs in April 2024.

Yesterday’s decision, joined in by Circuit Judge John B. Owens and District Court Judge John Charles Hinderaker of the District of Arizona, sitting by designation, reverses and remands with instructions to enter judgment in the plaintiffs’ favor on the issue of liability.

Shared Royalties

On appeal, the plaintiffs argued that the agreement obligates the defendants to share royalties according to its terms for as long as the covered songs continue to generate revenue. Wardlaw wrote:

“Construing the 1977 Agreement in light of California law, we agree.” The jurist said that “it is well-established under California law that if a contract contains no express term of duration, and the nature and surrounding circumstances of the contract do not permit the court to imply a term of duration, the contract is construed as terminable at will after a reasonable time.”

Taking no issue with Birotte’s determination that the contract contained “no express duration,” she turned to the question of whether an end date could be implied from the nature and surrounding circumstances of the agreement, and opined:

“[T]he nature of the 1977 Agreement establishes that the parties’ obligations under the contract will exist so long as the ‘song writing and publishing royalties (and/or other income) derived from the parties’ songwriting and/or publishing activities’ continue to flow.”

No Perpetual Obligation

Rejecting an assertion that this implied durational term is a “perpetual obligation,” she remarked:

“Not so. At some point in the future, the copyrights in the works covered by the 1977 Agreement will expire, and the works will fall into the public domain. At this point, the copyrights will cease to generate publishing royalties, and the obligations created by the 1977 Agreement will terminate….True, this may be many years down the line—but the ‘mere fact that an obligation under a contract may continue for a very long time is no reason in itself for declaring the contract to exist in perpetuity or for giving it a construction which would do violence to the…intent of the parties.’ ”

The defendants argued that the court cannot find that there is an implied termination point because the evidence supports multiple possible intended periods of duration. Wardlaw responded by saying:

“T]he proper inquiry is not whether an ascertainable event could imply termination, but whether that event ‘necessarily implies termination.’ ”

She added that “[a]lthough the purpose and nature of the 1977 Agreement alone establish its implied duration…, we agree…that Defendants’ predispute…conduct further supports that the parties…understood that they would continue to share in publishing and songwriting revenues for as long as the…songs continue to generate such revenues,” pointing to the fact that the defendants paid the royalties according to the agreement for over 40 years.

The case is Thomson v. Hodgson, 24-2858.

Copyright 2025, Metropolitan News Company