Page 3

Ninth Circuit:

‘Gone in 60 Seconds’ Car Not Entitled to Copyright Protection

By a MetNews Staff Writer

|

|

|

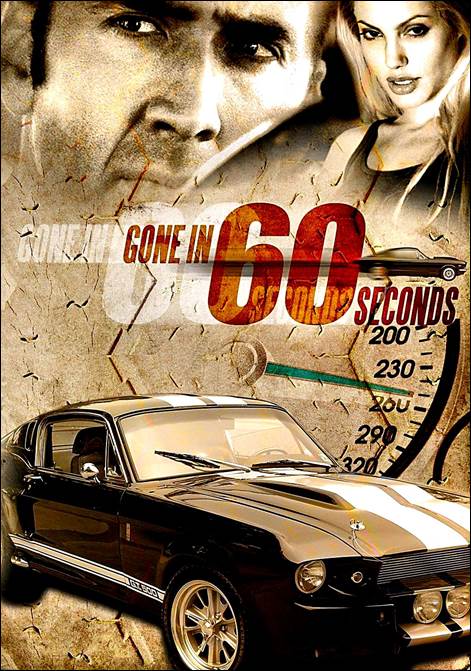

Above is a poster promoting the 2000 remake of “Gone in 60 Seconds,” featuring a vehicle referred to in the film as “Eleanor.” The Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals held yesterday that the vehicle, featured in a series of films, is not a character subject to copyright protection because—in apparent contradistinction to “Herbie” in Disney films and “KITT” in the Knight Rifer television series and spin-offs—”has no anthropomorphic traits.” |

A collection of Ford Mustangs referred to as “Eleanor” and featured across four films—including the original 1974 movie “Gone in 60 Seconds” and the 2000 remake bearing the same name—is not a “character” capable of copyright protection, the Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals held yesterday.

In an opinion, authored by District Court Judge Jeremy D. Kernodle of the Eastern District of Texas, sitting by designation, the court said that the collection of cars was “more akin to a prop than a character” and lacks the conceptual qualities, consistent traits, and distinctive nature of a protectable creation.

The question arose in litigation between Denice Halicki—widow of the writer, director, and star of the 1974 film—and entities affiliated with the late automotive designer Carroll Shelby. Halicki owns copyrights to the original “Gone in 60 Seconds” movie and two other films that operate in the same fictional universe, as well as merchandising rights relating to “Eleanor” in the 2000 remake.

“Eleanor” was the name given in the 1974 film to four different yellow and black Fastback Ford Mustangs that the protagonist is charged with stealing. In the 2000 remake, “Eleanor” is the name given to two Shelby GT-500 Ford Mustangs, one of which is gray with black stripes and the other is a rusted-out version of the car.

Following the remake’s release, entities affiliated with Shelby, who collaborated with Ford to create the performance Shelby Mustang GT-500 in 1967, contracted with a custom car shop to produce a GT-500E Mustang. Halicki sued, claiming the “E” in the title of the car referred to “Eleanor” and that the model unlawfully copied the vehicle from the film.

Halicki and the Shelby entities ultimately settled that lawsuit in 2009, agreeing, in part, that the designer would not copy any features specific to Eleanor. However, not long after the parties entered into the settlement agreement, the Shelby entities hired Classic Recreations LLC (“CR”) to produce a new version of the Mustang referred to as the “GT-500CR.”

Complaint Filed

After Halicki demanded that CR cease production of the vehicles, Carroll Shelby Licensing and the Carroll Hall Shelby Trust filed a complaint against Halicki and affiliated companies, Eleanor Licensing LLC and Gone in 60 Seconds Motorsports LLC. The pleading, filed in 2020, asserts breach of the settlement agreement and other related causes of action.

In the complaint, the plaintiffs allege that the GT-500CR bears none of the elements unique to the Eleanor vehicles and claim:

“[T]he Eleanor vehicle in the 2000 Remake consisted of a 1960s variation of a SHELBY GT500 body with a mere two design elements that distinguish it…, namely, an exaggerated, raised hump feature on the hood…and two small headlights with custom molded 3-inch holds and 2-inch lights inset from each of the two main headlights….

“…[I]t cannot be disputed that the Shelby Parties…own, and have owned since approximately 1967, the trademarks and trade dress associated with the GT500….”

The plaintiffs sought a declaration that “SHELBY vehicles, including the GT500, which do not contain the Eleanor Hood, Eleanor Inset Lights, or any ELEANOR Marks, do not infringe on any of Defendants’ rights….”

Halicki countersued, asserting copyright infringement and breach of contract claims. She also named CR as a third-party defendant.

District Court’s View

District Court Judge Mark C. Scarsi of the Central District of California, in resolving cross motions for summary judgment, found that “Eleanor is not entitled to standalone copyright protection as a matter of law.” He granted, in substantial part, the Shelby parties’ motion on the issue of copyrightability.

Following a bench trial on the parties’ surviving claims, Scarsi said:

“All remaining claims and counterclaims are dismissed. The Court directs the Clerk to enter judgment consistent with this Verdict and the Court’s prior orders.”

He also denied the Carroll parties’ request for declaratory relief, citing the failure of the plaintiffs to succeed on the breach of contract cause of action.

Yesterday’s opinion, joined in by Circuit Judges Jacqueline H. Nguyen and Salvador Mendoza Jr., affirms the judgments, but reverses the denial of declaratory relief.

Protectable Characters

Kernodle pointed out that the Copyright Act of 1976, codified at Title 17 of the U.S. Code, is “silent as to…characters within…enumerated works” but noted that case law has extended protections to such depictions if they have physical and conceptual qualities, are recognizable with consistent, identifiable traits, and are sufficiently distinctive.

Turning to the first prong, he acknowledged that “[o]ur precedent has primarily focused on ‘physical’ qualities,” but wrote:

“[E]qually important are the ‘conceptual’ qualities that all characters inherently possess. These include anthropomorphic qualities, acting with agency and volition, displaying sentience and emotion, expressing personality, speaking, thinking, or interacting with other characters or objects.”

Distinguishing “Eleanor” from vehicles that have been found to be protectable, the jurist said:

“Eleanor has no anthropomorphic traits. The car never acts with agency or volition; rather, it is always driven by the film’s protagonists. Eleanor expresses no sentience, emotion, or personality. Nor does Eleanor speak, think, or otherwise engage or interact with the films’ protagonists. Instead, Eleanor is just one of many named cars in the films.”

In a footnote, Kernodle rejected Halicki’s assertion that the collection of cars identified as “Eleanor” do have anthropomorphic qualities, citing a moment in the remake where the engine sputters and dies as an indication of jealousy when the protagonist’s girlfriend gets into the vehicle. He commented:

“[T]his is pure speculation….This version of Eleanor was rusty, old, and in clear need of maintenance work. A reasonable viewer attributes the breakdown to the car’s poor condition, not Eleanor’s feelings.”

Lacks Consistent Traits

As to recognizability, he opined:

“Here too, Eleanor fails. Across four films and eleven iterations in those films, Eleanor lacks consistent traits. For example, Eleanor’s physical appearance changes frequently throughout the various films, appearing as a yellow and black Fastback Mustang, a gray and black Shelby GT-500 Mustang, and a rusty, paintless Mustang in need of repair. Indeed, the latter Eleanors are unrecognizable until introduced as Eleanor by the protagonists.”

The judge continued:

“Halicki claims Eleanor is always ‘incurring severe damage’ and is ‘hard to steal.’ But fewer than half of the Eleanors ever appear damaged at all, and the damage ranges from body damage incurred by a police chase, to cosmetic damage, to being entirely shredded for scrap. And of the Eleanors stolen by the films’ protagonists, most were stolen with little difficulty.”

Similarly, he reasoned that “Eleanor is not especially distinctive,” noting that “[n]othing distinguishes [it] from any number of sports cars appearing in car-centric action films.”

Turning to the breach of contract claim and counterclaim, he wrote:

“The dispositive issue here is whether the settlement agreement prohibits Shelby from manufacturing or licensing cars copying (1) any of Eleanor’s distinctive features or (2) only Eleanor’s distinctive hood and inset lights. The district court held that the latter interpretation was correct. We agree.”

Declaratory Relief

However, he said that Scarsi erred in denying declaratory relief, saying that such a remedy is appropriate under the Declaratory Judgment Act when it will “serve a useful purpose” in settling the legal disputes and will terminate uncertainty underlying the events giving rise to the proceedings. He concluded:

“This standard is met here. First, a declaration will clarify and settle the legal relations at issue between Shelby and Halicki….Second, a declaration will afford Shelby relief from the uncertainty giving rise to this proceeding. For example, Halicki issued a press release following the district court’s bench verdict making it appear that she will likely continue to hassle Shelby going forward based on the denial of declaratory relief. Halicki, moreover, has a history of mischaracterizing this Court’s opinions.”

Kernodle remarked that “it is appropriate to remand the issue for full consideration by the district court in the first instance” given the fact-intensive nature of declaratory relief, but added:

“[W]e offer brief guidance on the proper scope. Shelby is entitled to a declaration that is consistent with what has been adjudicated in this case. Accordingly, it would seem appropriate to declare that the GT-500CR does not infringe on Halicki’s copyright interests in Eleanor or contractual rights under the settlement agreement.”

The case is Carroll Shelby Licensing Inc. v. Halicki, 23-3731.

Copyright 2025, Metropolitan News Company