Page 1

Court of Appeal:

Convictions of ‘Crooked’ Disbarred Lawyer Layfield Upheld

Ninth Circuit Rejects Contention That Government Violated Speedy Trial Act

By a MetNews Staff Writer

|

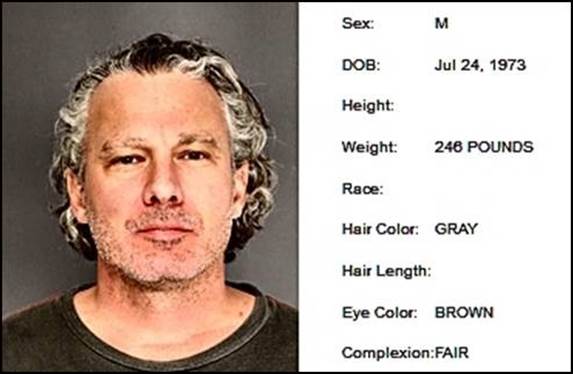

— Essex County Department of Corrections Disbarred lawyer Philip Layfield is seen in a booking photograph taken in New Jersey where he was apprehended at an airport where he planned to board a flight to Costa Rica. The Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals on Thursday affirmed his conviction on multiple counts in connection with stealing client funds and tax evasion. |

Disbarred lawyer Philip Layfield, who cheated numerous clients by stealing a total of $5,552,756 from settlement funds and who cheated on his income tax, has failed in an effort to persuade the Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals that his convictions should be overturned.

Judge John B. Owens, writing for a three-judge panel, described Layfield as “a crooked plaintiff’s lawyer and certified public accountant with operations in Los Angeles and elsewhere.”

Owens rejected Layfield’s contention that the government committed a Speedy Trial Act violation by virtue of a 21-day delay in transporting him from New Jersey, where he was arrested, to the Central District of California (“CDCA”), where a charge was pending against him for mail fraud. The 21-day period commenced, as Layfield reckons it, on May 2, 2018, when a magistrate judge of the U.S. District Court for the District of New Jersey denied bail and ordered his removal to Los Angeles, and it ended, he contends, on May 23 when he made his first appearance in CDCA.

70-Day Provision

The ex-lawyer argues that taking into account the three-week delay in transporting him, he was not brought to trial within 70 days, as required by law. In particular, he relied upon 18 U.S.C. §3161(c)(1), a portion of the Speedy Trial Act, which provides:

“In any case in which a plea of not guilty is entered, the trial of a defendant charged in an information or indictment with the commission of an offense shall commence within seventy days from the filing date (and making public) of the information or indictment, or from the date the defendant has appeared before a judicial officer of the court in which such charge is pending, whichever date last occurs.”

Owens responded:

“Under the clear language of § 3161(c)(1), only two events could trigger Layfield’s seventy-day speedy trial clock: (1) the March 9, 2018 public filing of the indictment or (2) his March 23, 2018 first appearance before a judge in the CDCA. And because his CDCA appearance was the latter date, it triggered the seventy-day clock. This plain reading of § 3161(c)(1) dictates that the twenty-one-day delay between his detention in New Jersey and his first appearance in the CDCA was immaterial to the Speedy Trial Act analysis.”

Unreasonableness Presumed

Layfield also pointed to §3161(h)(1)(F), which says that that, in calculating the 70 days, a “delay resulting from transportation of any defendant from another district...in excess of ten days...shall be presumed to be unreasonable.”

The Ninth Circuit judge responded that §3161(h)(1)(F) “readily applies when a prisoner, after § 3161(c)(1) is triggered, is transferred between districts for separate trial proceedings,” explaining:

“For example, the defendant may be subject to detainers lodged by other districts where charges are also pending against them. The first ten days of that travel are deemed reasonable. Days exceeding those ten are not.”

The 2007 case of United States v. Thompson from the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Florida was cited by Layfield in support of his reading of the subsection. Owens wrote: “The judge in that case, apparently frustrated that the government made no effort to explain a three-month delay in transporting the defendant, ruled that the speedy trial clock began with the order of removal….The court neither cited nor distinguished any authority but reasoned that ‘[t]o hold otherwise would render the relevant tolling provision, § 3161(h)(1)([F]), largely useless in situations such as this one, where the Order of Removal...was either ignored or forgotten about.’… Thompson holds limited, if any, value: no court has ever relied on it, and, by contrast, Layfield’s order of removal was not ignored.” The panel disposed of other contentions in a memorandum opinion.

One argument Layfield put forth was that nine of the 19 counts of wire fraud of which he was convicted must be reversed because what he did was deposit settlement funds in his firm’s trust account which was required under California law. The panel responded:

“The wires into the trust account were the result of the services that Layfield had falsely represented he would perform in accordance with his fiduciary duty to protect and hold their funds in trust. In other words, Layfield’s fraudulent representations led to the firm’s services to clients which in turn led to the receipt of settlement funds that were then deposited into the trust account.”

Other challenges were also rejected.

Layfield, also known as Philip Samuel Pesin, was disbarred on Oct. 27, 2018, convicted by a jury on Aug. 26, 2021 on multiple counts, and was sentenced on Feb. 17, 2022, by District Court Judge Michael W. Fitzgerald to 12 years in prison.

Copyright 2024, Metropolitan News Company