Page 1

Ninth Circuit:

No Violation in Forced Use of Thumb to Unlock Phone

Compelled Use of Biometric Was Found to Be Not Testimonial for Purposes of Fifth Amendment Analysis

By Kimber Cooley, Staff Writer

|

|

|

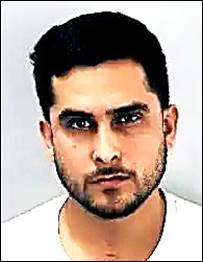

JEREMY TRAVIS PAYNE criminal defendant |

The Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals held yesterday that an officer’s grabbing of a criminal suspect’s thumb and using it to unlock a phone found in the vehicle in which the suspect was riding was not in violation of either the Fourth or Fifth Amendments, as the suspect was on parole and subject to search conditions and the act, though incriminating, was not testimonial.

The opinion, authored by Senior Circuit Judge Richard C. Tallman, affirms the denial of a motion to suppress evidence by District Court Judge Percy Anderson of the Central District of California. It answers a question left open by existing Fifth Amendment precedent.

“To date, neither the Supreme Court nor any of our sister circuits have addressed whether the compelled use of a biometric to unlock an electronic device is testimonial,” Tallman wrote.

Circuit Judge Consuelo Callahan and Senior District Court Judge Robert S. Lasnik of the Western District of Washington, sitting by designation, joined in the opinion.

Traffic Stop

Appealing his conviction for possession of fentanyl with intent to distribute at least 40 grams was Jeremy Travis Payne, arrested on Nov. 3, 2021, after California Highway Patrol Officer Christian Coddington stopped him for a vehicle code violation. Payne admitted to the officer that he was on parole which Coddington confirmed.

His earlier conviction stemmed from a 2018 assault with a deadly weapon on a police officer.

Payne said he had a phone in the vehicle but denied that it was his and refused to supply the passcode. According to Payne, Coddington then forcibly grabbed his hand and used his thumb to unlock the phone, which contained videos showing a room with suspected illegal narcotics and a large amount of currency as well as the location of a parked vehicle, which eventually led to the officers to the home shown in the video.

The execution of a search warrant of the home revealed 104.3 grams of fentanyl, cocaine and $13,992 in cash.

|

|

|

—Riverside County Sheriff’s Department Depicted are Items found during a Nov. 3, 2021 search of the Palm Desert home of Jeremy Travis Payne whose conviction on a drug charge was affirmed yesterday by the Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. |

After Anderson denied his motion to suppress the searches of his phone and home under the Fourth and Fifth Amendments, Payne entered a conditional guilty plea and was sentenced to 144 months in prison.

Fifth Amendment Analysis

Tallman explained:

“For a criminal defendant to benefit from the Fifth Amendment privilege, there must be a ‘communication’ at issue that is: (1) compelled; (2) incriminating; and (3) testimonial.”

The compulsory and incriminating nature of the act were easily established, so Tallman said he was left with “the more difficult question” of whether the compelled use of Payne’s thumb to unlock the phone was “testimonial” in nature.

Noting that a testimonial communication is one that, explicitly or implicitly, relates factual assertions or discloses information, Tallman said:

“[Payne’s] Fifth Amendment claim thus rests entirely on whether the use of his thumb implicitly related certain facts to officers such that he can avail himself of the privilege against self-incrimination. This argument implicates two lines of Supreme Court precedent: the physical trait cases and the act of production doctrine.”

Physical Trait Cases

The physical trait line of cases holds that physical acts, such as those requiring a person to serve as a donor for actions like fingerprints and blood draws, are not testimonial because such acts do not involve the “testimonial capacities” of the accused. Applying the doctrine to Payne’s case before him, Tallman opined:

“[T]he use of Payne’s thumb to unlock his phone appears no different from a blood draw or fingerprinting at booking. These actions do not involve the testimonial capacities of the accused and instead only compel an individual to provide law enforcement with access to an immutable physical characteristic.”

The heart of Payne’s argument instead relies on the act of production doctrine under which a purely physical act may be testimonial because of what it communicates.

Act of Production

Tallman noted that district courts have “arrived at different conclusions on the biometric unlock question.” Some courts, he recited, have found the compelled use of a biometric identifier to be analogous to forcing the person to turn over their alphanumeric passcode—an act that is generally accepted to be protected by the Fifth Amendment because it requires an individual to divulge the contents of his mind.

Finding this argument to be unpersuasive, the jurist commented:

“The logic goes: biometrics are the equivalent of or a substitute for a passcode and passcodes are protected under the Fifth Amendment, so, biometrics are also protected under the Fifth Amendment. The flaw lies in the fact that the Supreme Court has framed the question around whether a particular action requires a defendant to divulge the contents of his mind, not whether two actions yield the same result.”

No Intrusion

He continued:

“When Officer Coddington used Payne’s thumb to unlock his phone—which he could have accomplished even if Payne had been unconscious—he did not intrude on the contents of Payne’s mind.”

He found lacking Payne’s argument that the testimonial nature of the act related to the fact that the use of his thumb to unlock the device confirmed ownership of the device and wrote:

“While the fact that Payne’s thumb unlocked the phone proved to be incriminating, it alone certainly did not serve to authenticate all the phone’s contents.”

He concluded that “the use of Payne’s thumb to unlock his phone was not a testimonial act and the Fifth Amendment does not apply.”

Tallman specified that “Fifth Amendment questions like this one are highly fact dependent” and the “opinion should not be read to extend to all instances where a biometric is used to unlock an electronic device.”

Fourth Amendment

Payne also challenged the search of the phone on Fourth Amendment grounds. Despite his parole status entailing general search conditions, set forth in an agreement he signed in 2020, Payne argued that a special condition, contained in an attachment, governed. It provides that he was to surrender his phone and provide a pass key to unlock the device to any law enforcement officer upon demand, specifying:

“Failure to comply can result in your arrest, pending further…confiscating of any device pending investigation.”

Payne posited that the parole-search exception to the warrant requirement cannot apply when officers do not follow the precise terms of the parole conditions, and his special condition did not permit the forced use of biometrics to access his phone.

Tallman dismissed this argument and reasoned that the general search condition was sufficient to justify the search, saying:

“[W]e hold that the inclusion of Payne’s special search condition did not vitiate the force of his statutorily mandated general search condition, which independently authorized the search at issue in this case.”

The case is United States v. Payne, 22-50262.

Copyright 2024, Metropolitan News Company