Page 8

In My Opinion

California’s First Chief Justice, Family, Subjected to Legislative Attainder

By Kristian Whitten

On March 26, 1878, the Legislature created a law school to be part of the state university. It was, under the legislation, “to be forever known and designated as ‘Hastings College of the Law,’ ” named after its founder and benefactor, Serranus Clinton Hastings. Better known in his lifetime as “S.C. Hastings,” he was the first chief justice of California.

Last Sept. 23, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed into law AB 1936 which renamed Hastings College of the Law “the College of the Law, San Francisco.”

S.C. Hastings has, in recent years, come into disrepute. Section 1 of the bill recites:

(q) S.C. Hastings, founder of the Hastings College of the Law, promoted and financed Native American hunting expeditions in the Eden and Round Valleys, funding bounties resulting in the massacre of hundreds of Yuki men, women, and children.

(r) S.C. Hastings enriched himself through the seizure of large parts of these lands and financed the college of the law bearing his namesake with a $100,000 donation.

(s) S.C. Hastings and the state bear significant responsibility for the irreparable harm caused to the Yuki people and the Native American people of the state.

(t) The state has formally apologized to the Native American people of the state for the genocide financed and perpetrated by the state.

(u) S.C. Hastings' name must be removed from the College to end this injustice and begin the healing process for the crimes of the past.

However, the opinion piece below recites that the Legislature’s investigation contemporaneous with the events, including live testimony, exonerated Hastings of the very charges found true more than a century-and-a-half later.

Litigation has been commenced by some alumni challenging the legality of the name-change. The author of the article below is active in that litigation.

(The writer is a retired California deputy attorney general. He graduated from UC Hastings College of Law in 1973. This is his second opinion piece here on the subject.)

Suddenly, in one fell swoop, the State Bar of California has personalized the name change of Hastings College of the Law for all of its graduates who are or were members of the State Bar by amending our personal information that appears on the State Bar website to say that we graduated from: “UC College of the Law, San Francisco.” But see Sander v. State Bar (2013) 58 Cal.4th 300, 305 (the State Bar maintains “information obtained from applicants through the admissions process....”); California Business & Professions Code §6060(e)(1) (that information may include the ABA accredited law school that conferred a J.D. degree).

|

|

|

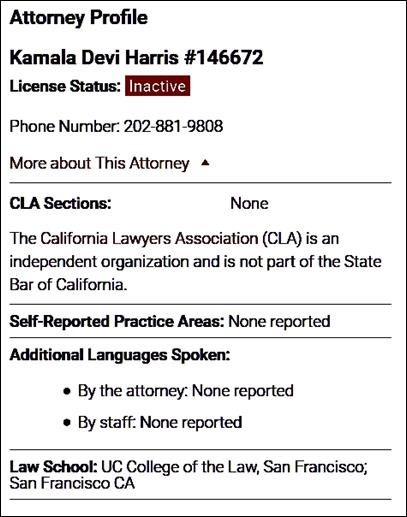

Above is a screenshot of Vice President Kamala Harris’s profile on the State Bar of California website. Those, such as she, who graduated from what was known when they received their degrees as the “Hastings College of the Law,” are now listed as graduates of “UC College of the Law, San Francisco,” following a legislative name-change. |

Besides being an inaccurate statement of fact, the new law enacting the name change does not clearly indicate that it is meant to be retroactive. See generally City of Emeryville v. Cohen (2015) 233 Cal.App.4th 293, 308.

One of the causes of action in the pending litigation against the law school and the state alleges the provisions in AB 1936 that change the school’s name and removes the Hastings family seat on its Board of Directors constitute an unconstitutional bill of attainder.

★

In Nixon v. Administrator of General Services (1977) 433 U.S. 425, the court explained a major concern that prompted the Constitution’s bill of attainder prohibition: “the fear that the legislature, in seeking to pander to an inflamed popular constituency, will find it expedient openly to assume the mantle of judge—or, worse still, lynch mob.”

In that case, the court held that a law requiring former President Richard Nixon to turn over presidential papers and recordings to an official of the Executive Branch was not a bill of attainder, because it was not passed by Congress to punish him.

But in United States v. Lovett(1946) 328 U.S. 303, 312, it found that a law supported by a House Committee on Un-American Activities that expressly characterized individuals as “subversive...and...unfit...to continue in Government employment” was a bill of attainder. In that case the court held that “[a] bill of attainder is a legislative act which inflicts punishment without a judicial trial....[L]egislative acts, no matter what their form, that apply either to named individuals or to easily ascertainable members of a group in such a way as to inflict punishment on them without a judicial trial are bills of attainder prohibited by the Constitution.” Id. at p. 315.

★

Based upon a recently created and erroneous historical narrative, AB 1936 states that its punitive purpose is to punish California’s first chief justice and his family for actions taken by Serranus Hastings over 150 years ago that characterizes as “crimes”—actions that were investigated and not deemed wrongful by the Legislature at that time.

Serranus Hastings testified under oath in that 1860 investigation, which concluded with no suggestion of his complicity in any atrocities committed against Native Americans in California. However, the substance and findings of those proceedings played no part in the current Legislature’s determination that the Hastings legacy must be banished from the law school.

This odyssey began with two California history professors who wrote academic papers and books that created a narrative that was widely adopted in the media. Apparently because of that, it has also been adopted by the California Legislature and governor. That narrative vilifies white settlers who came to California in the Gold Rush, and is built on the theory that land which the new State of California acquired from the United States after its war with Mexico, and then sold to settlers like Hastings, constitutes “the theft of California Indian land.” Thus, Serranus Hastings’ “theft...of Indian land” necessarily implicates him in the barbarous acts of those who committed horrific acts against Native Americans in California.

Thus, it is Hastings’ use of his land, and his application of state law to protect his and other settlers’ lives and property, that is the basis of the charge that he is responsible for wanton killing of Native Americans. However, there is no evidence that he killed or knowingly participated in the killing of any Native Americans, and the Legislature’s 1860 investigation into the Indian Wars did not implicate Serranus Hastings in the events now charged as crimes against him.

★

After a multi-year study, and with concurrence from the Round Valley Indian Tribes, the law school decided the name should not be changed.

Then suddenly, within a week of the publication of a New York Times front page story claiming that Serranus Hastings “masterminded one set of [Native American] massacres,” the law school’s Board of Directors succumbed to pressure from politically powerful alumni and legislators by requesting that the Legislature and governor change the school’s name.

As enacted, AB 1936 “finds” that Serranus Hastings “promoted and financed Native American hunting expeditions in the Eden and Round Valleys, funding bounties resulting in the massacre of hundreds of Yuki men, women, and children; enriched himself through the seizure of large parts of these lands..., [and] bear[s] significant responsibility for the irreparable harm caused to the Yuki people and the Native American people of the state.”

Those findings also refer to Hastings’ and the state’s conduct as “crimes.”

★

These findings retroactively and without a judicial trial “heap[] scorn [and] punishment upon” Serranus Hastings and his descendants. See “Akhil Reed Amar, America’s Constitution.” 125 (Random House 2005). In addition, removing the Hastings family board seat escheats to the state the family’s ongoing legal interest in the 144-year-old highly acclaimed product of Serranus Hastings’ 1878 beneficence. See Anthony Dick, “The Substance of Punishment Under the Bill of Attainder Clause,” 63 San. L. Rev. 1177, 1188 (2011) (“Bills of attainder...are state-engines of oppression in the last resort, and of the most powerful and extensive operation, reaching the absent and the dead, as well as the present and the living.”).

Contrast this process with that which followed to remove the name “Boalt” from the building housing U.C. Berkeley Law. Following university-wide policies and protocols requiring campus chancellors to “seek the widest possible counsel when considering proposals for naming or renaming,” that U.C. law school solicited and received more than 2,000 comments, engaged in historical research, and held a public forum. Its report was then widely circulated, receiving over 600 responses, and the law school received thousands of additional comments from alumni.

That report also addressed other notable individuals like former U.S. Chief Justice Earl Warren, who as California’s attorney general, supported the internment of Japanese Americans during WWII, concluding that his later contributions to the school and the state support honoring him.

That law school’s report was then submitted to the Chancellor’s Building Name Review Committee, which announced the law school’s report campus-wide, posted it on the campus website, and solicited comments.

No such thorough consultative process preceded the decision to remove the Hastings name and board seat. Indeed, at one hearing in the state Senate, those of us who spoke in opposition to that effort faced accusations that our raising the issue of the 1860 legislative investigation and questioning the controlling narrative parroted in the New York Times was “fake news.”

★

Soon after the law school’s founding in 1878, and contrary to the advice of its founder and then-dean, Serranus Hastings, its Board of Directors voted to ban women students. Validating Hastings’ belief that “the law [was] with the ladies,” the California Supreme Court held that because it is affiliated with the University of California, which admits women, women must be eligible for admission to Hastings College of the Law.

In that case the court said:

“An affiliation imports a subjection to the same general laws and rules that are applicable to the parent institution, with such special exceptions as may be expressly made, and such as arise from the very nature and purpose of the affiliated institution.”

Foltz v. Hoge (1879)54 Cal. 28, 34.

The UC Hastings’ Board of Directors did not follow de-naming procedures anything like those mandated by the university with which it is affiliated. However, the transparency and due process missing in the run up to the approval of AB 1936 will apply in the “judicial trial” to come. United States v. Lovett, supra, 328 U.S. at p. 315.

Copyright 2023, Metropolitan News Company