Page 9

Renaming Hastings College of Law Impairs a Contract

By Kristian Whitten

|

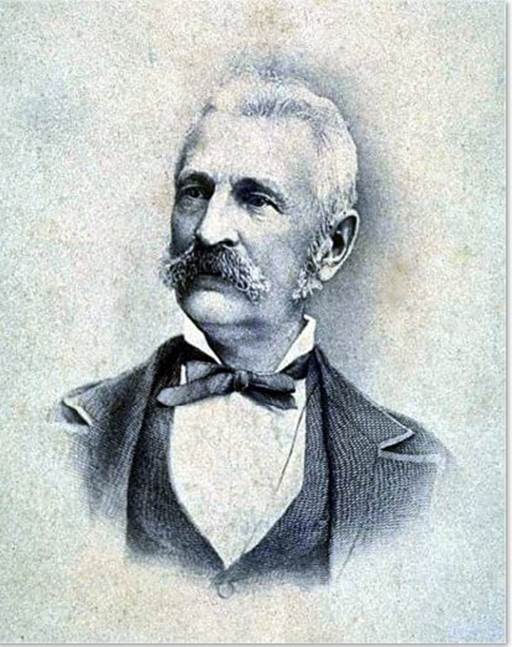

Pictured above is Serranus Clinton Hastings (1814-1893)—more commonly known during his lifetime as S.C. Hastings. He was California’s first chief justice (from 1849, before statehood in 1850, until 1851) and was the state’s third attorney general (1852-54). A charge made against Hastings during the late 1850s—and denied by him—was that he was an organizer of the massacre of members of the Yuki tribe of native Americans. A 2017 op-ed piece in the San Francisco Chronicle drew attention to the allegation anew and an effort was commenced to strip Hastings’s name from the University of California Hastings College of Law. Under legislation enacted last year, the name of the institution is now “University of California College of the Law, San Francisco.” However, litigation is in progress asserting that the name-change is unlawful because the law school, founded on March 28, 1878, was funded by Hastings’s gift of $100,000 in gold coins, with the proviso that, in exchange for the donation, the school was to be named in honor of the benefactor in perpetuity. San Francisco Superior Court Judge Richard B. Ulmer on Dec. 30 denied a motion for a preliminary injunction. |

(The writer is a retired California deputy attorney general. He graduated from UC Hastings College of Law in 1973 and is active in the name-change litigation.)

The litigation in San Francisco Superior Court against the former Hastings College of the Law, filed by heirs of its founder and its alumni over the new name for the law school, resulted in a Dec. 30, 2022 order denying the plaintiffs’ motion for a preliminary injunction to prevent the new name from going into effect. Thus, the renaming occurred on Jan. 1.

At the hearing, the law school’s counsel, Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher’s Theodore Boutrous, argued, and the court ruled, that: “[t]he 1878 act that created the law school is a statute, not a contract,” thus finding it unlikely that plaintiffs will succeed on their claim that the Legislature’s renaming legislation violates the Contracts Clauses in the state and federal Constitutions because it impairs a contract that requires the law school to “forever” be named “Hastings College of the Law.”

However, the court’s order does not address the fact that a year after it was created, in Foltz v. Hoge (1879) 54 Cal. 28, the law school’s counsel described Serranus Hastings’ founding of the college by paying $100,000 in gold coin to the State in exchange for agreed-upon terms that were contained in legislation as “a complete contract between Hastings and the State; . . a private eleemosynary perpetual trust, . . .” citing “Dartmouth College Case, 4 Wheat. 673-6.”

Nor does it discuss Trustees of Dartmouth College v. Woodward (1819)17 U.S. 518, 627, where the court found from that college’s charter application that large contributions were made, which were paid to the college as soon as it was created:

“The charter is granted, and on its faith the property is conveyed. Surely in this transaction every ingredient of a complete and legitimate contract is to be found.”

The court then determined that the State’s changing the terms of that contract ex post facto impaired it, in violation of the U.S. Constitution’s Contracts Clause. See also United States Trust Co. v. New Jersey (1977) 431 U.S. 1, 18 (acknowledging that, “the obligation was itself created by a statute [and] the purpose of the covenant was to invoke the constitutional protection of the Contract Clause as security against repeal”).

Duke University Law Professor Ernest Young wrote:

“The contract in Dartmouth College was the college’s charter itself – that is, it was an agreement that not only formalized a transaction, but created an institution. The Supreme Court’s holding that the State of New Hampshire could not retroactively alter the terms of the charter established dear old Dartmouth’s autonomy from government control.”

Ernest Young, Dartmouth College v. Woodward and the Structure of Civil Society, 18 U.N.H.L.Rev. 41, 42 (2019).

And he also notes:

“The Contracts Clause retains more force in cases involving the State’s own agreements than it does with respect to regulation of private contracts....”

In Coutin v. Lucas (1990) 220 Cal. App. 3d 1016, 1020, the Court of Appeal described “the 1878 act originally establishing Hastings College of the Law” as containing “terms of the private trust of Serranus C. Hastings.” One of those terms is: “The law college founded and established by S.C. Hastings shall forever be known and designated as the Hastings College of the Law.” Former Education Code §92200.

In a July 2017 article recounting an interview, the law school’s chancellor and dean, David Faigman, is quoted as saying that “removing the name could violate the trust agreement made with the state 139 years ago when [Serranus Hastings] gave the money to start the school.” Karen Sloan, Racist Pasts of Boalt Hall and Hastings’ Namesakes Haunt Law School.

The case is now before the Court of Appeal in San Francisco as a result of the law school’s appeal of the denial of its motion to dismiss plaintiffs’ complaint, that it claimed is “a meritless strategic lawsuit against public participation” (anti-SLAPP motion) under Code if Civil Procedure §426.16.

|

|

|

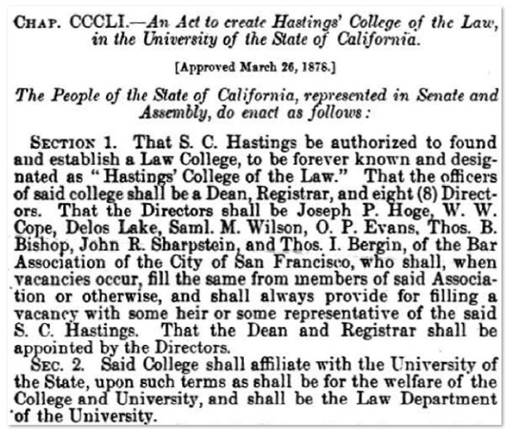

Sec. 1 of the 1876 act creating the Hastings College of Law specifies: “That S.C. Hastings be authorized to found and establish a Law College, to be forever known and designated as ‘Hastings College of the Law.’ ” That supposed never-ending designation ended 144 years later when the institution was renamed, which spawned litigation. The act said that Hastings would be the University of California’s “Law Department.” It is the oldest law school in the state, commencing operations on Aug. 12, 1878. |

Copyright 2023, Metropolitan News Company

MetNews Main Page Reminiscing ColumnsCopyright 2023, Metropolitan News Company