Page 1

Ninth Circuit:

California High Court Erred in Upholding Death Sentence

District Court’s Granting of Habeas Relief Based on Ineffective Assistance of Counsel at Penalty Phase Affirmed

In Opinion by Wardlaw, Watford; Miller Argues That Any Deficiency on Part of Lawyer Was Not Prejudicial

By a MetNews Staff Writer

|

|

|

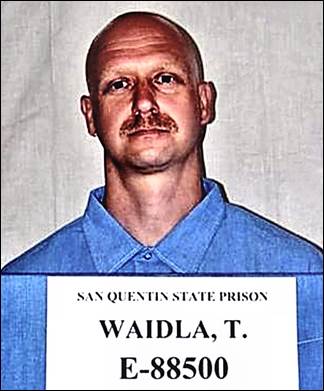

TAUNO WAIDLA convicted murderer |

The Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, in a 2-1 decision, yesterday affirmed the District Court’s granting of a petition for a writ of habeas corpus relieving an axe murder of a death sentence that had been affirmed by the California Supreme Court.

Circuit Judges Kim McLane Wardlaw and Paul J. Watford signed the per curiam opinion approving of the action by District Court Judge Andrew J. Guilford of the Central District of California in providing relief to Tauno Waidla, convicted of first-degree murder in the course of a burglary and robbery, with personal use of a deadly and dangerous weapon. He was sentenced by Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Howard J. Schwab (now deceased) on Dec. 5, 1991 to be executed.

Wardlaw and Watford rejected Waidla’s cross-appeal from Guilford’s denial of guilt-phase relief while spurning the State of California’s appeal from the District Court judge’s invalidation of the sentence on the ground of ineffective assistance of counsel at the penalty phase. Circuit Judge Eric D. Miller agreed that the cross-appeal lacked merit but asserted that his colleagues erred in countermanding the state Supreme Court’s determination.

“The California Supreme Court considered Waidla’s claim of ineffective assistance of counsel and rejected it on the merits,” Miller wrote. “That decision requires our deference, and I would reverse the judgment below to the extent that it granted habeas relief.”

Mosk’s Opinion

The state high court affirmed the judgment of guilt and the sentence on April 6, 2000, in an opinion by Justice Stanley Mosk (now deceased), and certiorari was denied by the U.S. Supreme Court on Nov. 27, 2000.

In seeking habeas relief in the District Court, Waidla’s lawyer, Deputy Federal Public Defender Scott T. Johnson argued:

“After failing in his representation of Mr. Waidla in the guilt phase of his trial, counsel did not present any evidence at the penalty phase of the trial. Not a single witness was called. This unique penalty phase presentation reflected counsel’s utter failure to conduct any of the constitutionally-required investigation into his client’s background that is called for in death penalty cases. Counsel’s ineffective representation was all the more egregious in view of the fact that Mr. Waidla had achieved so much during his young life in both school and competitive sports while growing up in Estonia.”

Guilford’s Ruling

In granting relief on Dec. 18, 2017, on bases not considered by the state Supreme Court on appeal, Guilford recited that under the United States Supreme Court’s 1984 decision in Strickland v. Washington, “[t]o prevail on a claim of ineffective assistance of counsel…, there must be a showing that (1) counsel’s conduct fell below an objective standard of reasonableness (i.e, was ‘deficient’), and (2) the defendant was prejudiced thereby.”

That burden was met, he said, setting forth:

“[T]he Court finds that trial counsel’s performance at the penalty phase of Petitioner’s trial was clearly deficient in light of counsel’s complete failure to investigate or present mitigation evidence, which includes information regarding Petitioner’s childhood and background (beyond the very limited guilt phase references), his pro-social behavior, lack of future dangerousness, and positive adjustment to incarceration.”

He held that “[a]t a minimum, the evidence that was available but not presented would have ‘humanized’ Petitioner to the jury.”

Ninth Circuit Opinion

Agreeing with Guilford, Wardlaw and Watford said:

“We hold that the California Supreme Court unreasonably applied Strickland’s standard in evaluating Waidla’s claim of ineffective assistance at the penalty phase. Had the three categories of evidence that counsel should have discovered been presented to the jury, there is a reasonable probability that at least one juror would have voted against the death penalty.”

How the California Supreme Court misapplied Strickland is not made clear. Mosk made a single reference to that case and his only discussion of the purported inadequacy of counsel at the penalty stage was this:

“Waidla contends that his counsel provided ineffective assistance under the Sixth Amendment’s counsel clause by failing to attempt to introduce, for mitigation, evidence of a portion of a confession that [accomplice] Sakarias assertedly made to the police, which was assertedly admitted at Sakarias’s later trial.

“We reject the claim at the threshold. The record on appeal does not include any confession by Sakarias. Therefore, we conclude that the point must be raised, if at all, by petition for writ of habeas corpus rather than on appeal.”

In her March 3, 2005 opinion in In re Sakarias in which Waidla was denied habeas relief (but which was granted to Sakarias based on misconduct by then-Deputy District Attorney Steve Ipsen), then-Justice Kathryn M. Werdegar made no mention of Strickland.

Soviet Defector

Waidla, born in Estonia, was, as a teenager, conscripted into the army of the Soviet Union, of which Estonia was a part. He and Sakarias, stationed in East Germany, escaped to West Germany and each gained asylum in the United States.

The hardships encountered in the army were recounted by Waidla in an article, “Escaping Through the Fog.”

Wardlaw and Watford wrote:

“[C]ounsel did not argue that Waidla’s hardships were relevant to the jury’s decision, nor did he attempt to obtain additional contextual evidence about the indignities visited on Estonian conscripts in the Soviet Army.

“Had counsel investigated, he would have found that in addition to the crowded lodging, repeated exposure to bitter cold, and inadequate medical care described in Waidla’s article, Estonian soldiers often encountered serious physical abuse and even death at the hands of Russian soldiers and officers. Counsel would have learned of the psychological impact that looming danger had on Waidla, whose letter to his family begging for help spoke to his despondency and fear. Armed with this evidence, competent counsel would have argued that Waidla’s time in an abusive institutional setting detracted from his culpability.”

Waidla’s lawyer, Martin R. Gladstein (now on inactive status) was also remiss in not looking into Waidla’s childhood experiences, as well as pointing to the client’s good behavior while awaiting trial, the majority’s opinion says.

“[C]ompetent counsel would have made the jury aware of Waidla’s many positive character traits. One such trait was Waidla’s strong work ethic,” Wardlaw and Watford wrote, adding:

“[C]ompetent counsel would have presented the humanizing evidence about Waidla’s strong bonds to family members.”

Miller’s Opinion

In his partial dissent, Miller argued that under the circumstances of the crime, any deficiency on the part of the lawyer at the penalty phase was not prejudicial. The victim was Viivi Piirisild, 52, who was vice-president and secretary of the Baltic American Freedom League and a radio broadcaster and writer.

She and her husband provided a place to live for Waidla and Sakarias. The conflict that precipitated the slaying was Waidla’s demand that he either be paid $3,000 for work he had done around the house of be given her automobile.

Miller wrote:

“…Waidla was not satisfied with the Piirisilds’ generosity. He became convinced that they also owed him a car. When they refused to give it to him, he broke into their house and murdered Viivi by splitting open her head with an axe.”

Brutal Killing

He went on to say:

“Waidla bludgeoned Viivi with the blunt end of an axe with such force that he crushed her skull, fractured several bones, and knocked out her teeth. He then broke open her skull with the blade of the axe, cutting a flap of skull and scalp from the top of her head. The jury saw gruesome photos of Viivi’s wounds.

“Was there provocation for this brutal attack? Not at all. Viivi had invited Waidla to live in her home when he had nowhere else to go, and she allowed him to stay for more than a year. She tried to find him work and offered to pay for his college education. She helped Waidla translate the article that he would use at his trial to argue that his life should be spared. And she brought him on trips to her family’s cabin, where Waidla later stole the axe that he would use to kill her.

“Did Waidla display remorse after the murder? Far from it. He wrote a note to his friend and accomplice celebrating his escape—‘Right now I am drinking Bavarian beer with the proper strength in one of the better class bars in Montreal”—and promising to go down ‘with a weapon in hand’ should he be apprehended: ‘If you hear that I have been taken alive...(almost impossible)...then you should know that I did my best.’ ”

Reason Noted

Miller pointed out:

“Waidla argues that counsel was ineffective because he did not obtain evidence about Waidla’s childhood in Estonia that could have humanized him to the jury. There was a good reason why counsel did not obtain such evidence: When counsel tried to investigate Waidla’s family background, Waidla told him not to do so. As counsel later explained, Waidla expressed considerable reluctance in having me contact his family or calling them as witnesses because ‘he was concerned about possible reprisals against his family by Soviet government or military authorities if they were to attempt to come to the United States and testify, because of his desertion from the Soviet army and escape from East Germany.’ Waidla himself had been the victim of Soviet reprisals. At trial, Waidla testified that when he was a student, the KGB had twice arrested him for protesting the regime, on one occasion beating him so badly that they broke his arm. Counsel repeatedly tested Waidla’s reluctance and suggested alternatives such as contacting his childhood teachers or other community members, but Waidla expressed the same concerns about reprisals against them. Waidla’s resistance was steadfast despite multiple conversations and proposals.

“Counsel’s ultimate decision to accede to Waidla’s wishes was far from unreasonable. To the contrary, it was consistent with professional standards….”

Experience in Army

Miller also argued that the jury “already had powerful evidence of the abuse that Waidla suffered” in the army, including the newspaper article he wrote.

He declared:

“In the end, the jury still would have been presented with a person who, after growing up in a totalitarian regime, had the extraordinary good fortune to escape it and find freedom in the United States—and then squandered that by becoming an axe murderer. Nothing in Waidla’s habeas petition has made any sense of that incomprehensible offense. It would be far from unreasonable to conclude that, with or without the new evidence, the jury’s verdict would remain the same.”

The case is Waidla v. Davis, 18-99001.

Copyright 2023, Metropolitan News Company