Page 1

Ninth Circuit:

Warrantless Searches of Massage Parlors Are Lawful

Opinion Limits Scope to California Businesses; Upholds South El Monte Ordinance

|

|

|

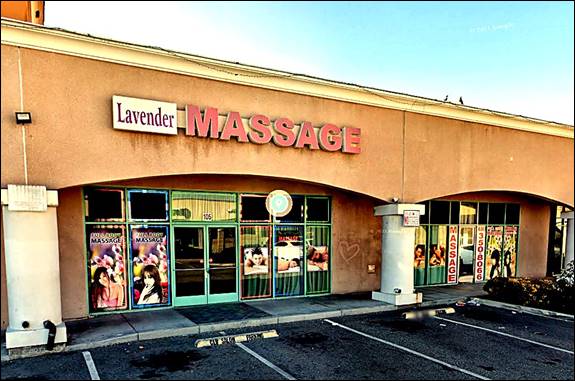

Depicted above is the front of Lavender Massage in South El Monte. The Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals yesterday upheld the validity of warrantless searches of such businesses pursuant to local ordinances.

|

By a MetNews Staff Writer

The Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals yesterday affirmed the dismissal with prejudice of an action against the City of South El Monte for alleged violation of the Fourth Amendment by conducting warrantless searches of a massage parlor.

Such businesses, Judge John B. Owens said in an opinion for a three-judge panel, are “closely regulated,” justifying warrantless searches where three conditions set forth in the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1987 opinion in New York v. Burger are met. Those conditions are satisfied with respect to the searches of Lavender Massage Center, he said.

The searches were conducted pursuant to an ordinance enacted in 2015 by the city council of South El Monte, located in the San Gabriel Valley east of Monterey Park.

Owens’s opinion was predicated on an opinion of the state Court of Appeal and California’s Massage Therapy Act, enacted in 2014. It specifies in a footnote:

“This opinion only concerns California businesses that qualify as a “massage establishment” under California Business and Professions Code section 4601(f). We render no opinion on businesses outside California or that do not qualify as a massage establishment under section 4601(f).”

That provision, contained in the Massage Therapy Act, specifies: “ ‘Massage establishment’…means a fixed location where massage is performed for compensation, excluding those locations where massage is only provided on an out-call basis.”

1985 Decision

For the proposition that massage parlors are closely regulated in California, Owens cited the Oct. 23, 1985 Court of Appeal decision of the Fourth District’s Div. Two in Kim v. Dolch. Affirming the denial of a petition for a writ of mandate challenging the constitutionality of an ordinance enacted in Victorville, located in San Bernardino County, the court held that warrantless search of such businesses are not violative of the Fourth Amendment.

“We find that the massage parlor industry is pervasively regulated,” Presiding Justice Margaret Morris (now deceased) wrote. “It has a history of regulation, albeit not as extensive as the liquor or firearms industries.”

Morris found that the requisites for warrantless searches of heavily regulated businesses were met.

She pointed out that “effective enforcement of the massage parlor ordinance in the instant case is contingent upon ‘unannounced, even frequent, inspections’ and, correspondingly, a warrant requirement would frustrate the purposes of the ordinance.”

Owens noted that with the adoption of the Massage Therapy Act, the massage industry is more heavily regulated now than in 1985 when the Court of Appeal issued its decision.

“[W]e hold that the California massage industry is ‘closely regulated’ and effectively reaffirm what has been the law in California for over 30 years,” he wrote.

Supreme Court Decision

Applying the criteria set forth in Burger, Owens said:

“First, there is no question that curtailing prostitution and human trafficking is a substantial government interest. Second, the warrant exception is necessary to further the regulatory scheme considering the potential ease of concealing violations.”

In connection with furthering the regulatory scheme, he noted that the Massage Therapy Act, the South El Monte ordinance under which the searches were conducted, and the conditional use permit that had been granted to the plaintiff, Phillip Killgore, “contain a variety of internal facility requirements.” These include, Owens recited, “a prohibition on unlicensed massage therapists, signage requirements, hygiene standards, a prohibition on sexual activities on the premises, and restrictions on permissible attire.”

Requiring a warrant, he said, “would only frustrate the government’s ability” to detect violations.

The third requirement of Burger—that legislation authorizing warrantless searches constitute a constitutionally acceptable substitute for a search warrant—was also met, the jurist declared, in that the city was reasonably restricted in conducting its searches, which were limited to specified hours.

Wilson’s dismissal of Killgore’s civil rights action challenging the revocation of his conditional use permit was afformed in a separate memorandum opinion.

The case is Killgore v. City of South El Monte, 20-55666.

Copyright 2021, Metropolitan News Company