Page 1

Court of Appeal:

Venue in Harassment Case Lies Where Defendant Resides

Man Who Received Upsetting Emails in Contra Costa County Was Not Entitled to Seek Restraining Order There Against Resident of Alameda Notwithstanding Implication of Judicial Council Form That He Could—Opinion

By a MetNews Staff Writer

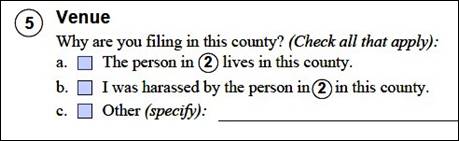

Venue in an action for a civil harassment restraining order lies exclusively in the county of the defendant’s residence unless there is a threat of physical injury in some other county, Div. One of the First District Court of Appeal Friday, rejecting the contention that deference must be accorded a Judicial Council form implying that venue alternatively lies in the county where harassment as occurred.

The plaintiff, Jefferey Fautt, contends that his action based on his receipt of allegedly abusive emails as properly filed in Contra Costa County where he resides, and relied upon Judicial Council form CH-100 (“Request for Civil Harassment Restraining Orders”). Paragraph b of that form asks for the name of the person to be restrained and this follows:

|

|

Fautt checked eb.

Defendant Ellen Williams sought a change of venue to Alameda County where she resides. Contra Costa Superior Court Gina Dashman denied the motion on the basis of the Judicial Council form.

“I have to believe that the Judicial Council knew what it was doing,” the judge said, remarking that it would not have formulated the “venue check option” as it did unless it thought its “words conveyed a correct basis for venue.” She said she would accord “deference” to the Judicial Council’s view.

Banke’s Opinion

Justice Kathleen Banke authored Friday’s opinion granting a writ of mandate ordering a change of venue to Alameda. “The general rule is that venue is proper only in the county of the defendant’s residence,” she wrote, going on to say:

“Moreover, when the plaintiff contends that the case fits within an exception to the general rule that venue is proper in the county of defendant’s residence, any ambiguities in the complaint must be construed against the plaintiff towards the end that the defendant will not be deprived of the right to a trial in the county of his or her residence.”

Supreme Court Opinion

She cited the California Supreme Court’s May 27 opinion in People v. Lemcke for the proposition that the Judicial Council, in formulating rules and forms, must adhere to statutory law. Banke pointed to Code of Civil Procedure §395(a) which says, in the first sentence:

“Except as otherwise provided by law and subject to the power of the court to transfer actions or proceedings as provided in this title, the superior court in the county where the defendants or some of them reside at the commencement of the action is the proper court for the trial of the action.”

Fautt argued the applicability of an exception. The next sentence of §395(a) says:

“If the action is for injury to person…, the superior court in either the county where the injury occurs…or the county where the defendants, or some of them reside at the commencement of the action, is a proper court for the trial of the action.”

Contra Costa County is where he was injured, Fautt contended, because that’s where he received the abusive emails from Williams—who was dissatisfied with his work as a contractor—and where “he has suffered substantial and serious emotional distress, and physical injury (a worsening of his underlying heart condition)”

1917 Decision

Banke drew attention to the California Supreme Court’s 1917 opinion in Graham v. Mixon, a libel case, in which it had “never regarded” §385 “as one which applies, so far as actions for personal injuries are concerned, to any but those based upon physical lesions.”

She also noted a 1923 high court decision saying that false imprisonment does not constitute a physical injury and a 1937 Court of Appeal opinion declaring that emotional distress is not such an injury.

“In light of this well-established authority, we must conclude Fautt’s allegations of physical ailment do not make his harassment claim one for ‘injury to person,’ ” she wrote.

The jurist did not disapprove the Judicial Council form, however. She explained:

“The second option set forth in the ‘Venue’ section of the Judicial Council CH-100 form—that the party seeking a restraining order ‘was harassed [by the party sought to be enjoined] in this county’—is not necessarily in conflict with the provisions of section 395. There may be cases in which the alleged harassment consists of abusive physical conduct by the harasser inflicting physical injury on the victim. Or, in other words, there may be harassment cases in which the locale where the alleged physical injury occurs is necessarily the locale where the events causing the injury occurred, and thus the injury has a definite situs.” Williams contended that a temporary restraining order against her was void because it was issued by the Contra Costa Superior Court. She lost on that point.

“Williams cites no authority suggesting, let alone holding, that emergency orders issued prior to the filing of motion to change venue are ‘void’ if the trial court subsequently determines the case is improperly venued and must be transferred to a different county,” Banke wrote. “Nor are we aware of any such authority.

“It is also well-established that venue is not a matter that goes to the fundamental jurisdiction of the superior court to hear and rule on a case.”

The case is Williams v. Superior Court, A163389.

Copyright 2021, Metropolitan News Company