Page 1

Court of Appeal:

Action Challenging Removal of Statue Depicting Indian Properly Dismissed

|

|

|

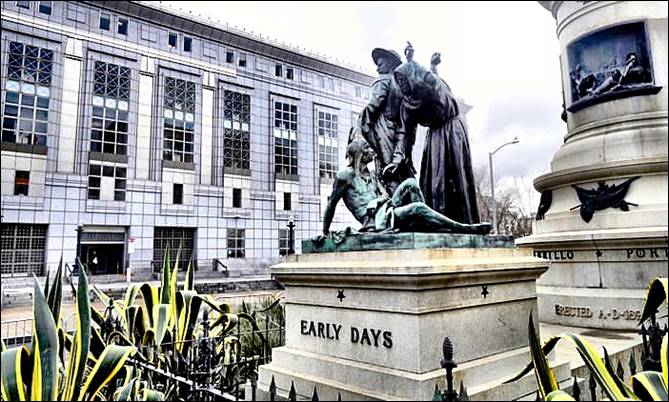

—AP Depicted above is the Early Days statue, prior to its removal from San Francisco’s Civic Center. The First District Court of Appeal on Monday affirmed the dismissal of an action challenging the removal of the sculpture in light of its offensiveness to native Americans. |

By a MetNews Staff Writer

Inventive arguments by a Sonoma County attorney, on behalf of himself and a Catholic practitioner, have failed to persuade the First District Court of Appeal that a judge erred in dismissing an action aimed at forcing the return to San Francisco’s Civic Center of an 1894 statue, now in a warehouse, depicting a priest bending over a reclining native American—a statue which some label “racist,” others hail as a work of art of historic value.

The statue, titled “Early Days,” had been one of five sculptures comprising “Pioneer Monument.”

At a public hearing in 2018, according to a news report, San Francisco’s director of cultural affairs said that “Early Days” had no rightful place on municipal property “any more than we should have a statue there of Robert E. Lee” and a tribal member termed the work a “monument to genocide,” while Petaluma attorney Frear Stephen Schmid argued that the statue was “the oldest piece of art in this area” and “an essential part of this national historic district.”

It was removed in the pre-dawn hours of Sept. 14, 2018, two days after the San Francisco’s Board of Appeals upheld the granting of a “certificate of appropriateness” (“COA”) by the city/county’s Historic Preservation Commission authorizing the dismantling of the statue.

Schmid, joined by San Francisco taxpayer Patricia Briggs, brought suit in San Francisco Superior Court for injunctive and declaratory relief. Judge Cynthia Ming-Mei Lee sustained a demurrer without leave to amend.

The judge noted that there had been “significant adverse public reaction over an extended period of time” to the statue. She found that Schmid and co-plaintiff Patricia Briggs lacked standing to contest the removal of “Early Days.”

The plaintiffs appealed from the judgment of dismissal. Affirmance came Monday in an opinion by Justice Jon Streeter of Div. Four.

“Despite Schmid’s vigorous opposition, the Board of Appeals had discretion to approve the issuance of the COA so long as its decision was supported by substantial evidence, which this decision was,” he declared.

Description of Statue

Streeter noted that at the November 1894 dedication ceremony for the statue, the speaker described it as “a group of three figures...consist[ing] of a native Indian reclining, over whom bends a Catholic priest, endeavoring to convey to the Indian some religious knowledge,” adding: “On his face you may see the struggle of dawning intelligence.”

The third figure, standing, is a vaquero, or herdsman.

As Briggs has described the work:

“The Indian is not fallen but in repose, as in many figures portrayed by the Renaissance masters. The padre, perhaps Junipero Serra, reaches down with one hand to raise him into the fold of Christianity; the other hand points toward heaven. The vaquero gazes on the horizon, perhaps toward distant cattle.”

Right to Preservation

Schmid claimed a “right to the preservation of fine art,” citing Civil Code §987(c)(1), a portion of the California Arts Preservation Act, which provides:

“No person, except an artist who owns and possesses a work of fine art which the artist has created, shall intentionally commit, or authorize the intentional commission of, any physical defacement, mutilation, alteration, or destruction of a work of fine art.”

Streeter responded:

“Schmid’s theory seems to be that any member of the public, on behalf of an artist who created a work of public art, has standing to enforce CAPA. Putting aside whether CAPA has not been preempted by a counterpart federal statute (…the Visual Artists Rights Act of 1991…) we disagree. These statutes create rights that are personal to artists. Only a person who created a work of art…or the heirs of such a person…may enforce them. Schmid’s attempt to invoke Civil Code section 987 fails because he does not allege either the destruction of ‘Early Days’—he admits it is in storage—or that he has authority to act on behalf of the artist who created ‘Early Days.’ ”

The artist was Frank Happersberger, who died in 1932.

Other Contentions

Among his various contentions, Schmid so sought to invoke the Tom Bane Civil Rights Act, Civil Code §52.1, which creates a cause of action for civil rights violations effected by means of “threat, intimidation, or coercion.” Streeter wrote:

“Assuming without deciding that appellants have adequately alleged the violation of rights amenable to Bane Act enforcement, nowhere does the first amended complaint allege anything that might reasonably be construed as ‘threats, intimidation or coercion’ to violate those rights.”

Schmid also argued that that the Board of Appeals, in upholding the COA, beached its public trust duties, noting that the duty has been held not to be restricted to ensuring access to tidelands and navigable waters. Broad as the duty is, Streeter said, “no court has ever held that this wide range of protected uses extends to viewing public art,” adding:

“We decline to be the first. While we have no doubt that public art is a valuable resource that should be available to all members of the public, it is not a natural resource.”

The jurist commented:

“It seems abundantly clear to us that, while ensuring the Pioneer Monument will continue to stand as a tribute to the pioneers for laying the foundation of the state we now know, the City decided as a policy matter that one aspect of the pioneers’ founding story—the stain of nativist racism—is no longer worthy of celebration. If Schmid and Briggs wish to change that policy judgment (it is reversible, after all, because “Early Days” was placed in storage, not shattered to pieces), nothing stops them from utilizing the electoral process as a means to continue advocating for their point of view.”

The case is Schmid v. City & County of San Francisco, 2021 S.O.S. Page 523.

Copyright 2021, Metropolitan News Company