Page 9

Perspectives (Column)

A Penal System Based on Rehabilitation Was Tried; Failed; Was ‘Dismantled’

Gascón Presents As a ‘Reform’ Something That Didn’t Work Before and Won’t Work Now

By Roger M. Grace

|

|

|

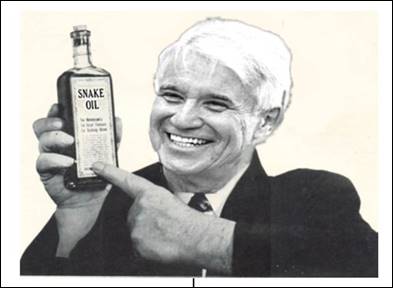

Like charlatans of old who peddled ineffectual nostrums, Los Angeles County District Attorney George Gascón, depicted in this composite photo, seeks to promote “rehabilitation” as the tonic that will cure the ills of the criminal justice system. |

Just as the “snake oil salesmen” of times past peddled largely inefficacious compounds that they hawked as astonishing cures for sundry ills, we have Los Angeles County District Attorney George Gascón touting rehabilitation as a remedy that will bring health and vitality to our criminal justice system.

He’s no more to be trusted than a 19th Century huckster vending mineral oil and prune juice as a tonic to relieve hives, insomnia, and menstrual pain.

“Dr. Gascón’s Miracle Elixir”—its main ingredient being “rehabilitation”—is proclaimed by our new district attorney to be a panacea, all that is needed to render the system in fit condition and provide beneficial treatment to those convicted of felonies.

That ingredient may, indeed, have some limited medicinal value, but it is, as proven, no cure-all.

Taking up where yesterday’s column left off: the Indeterminate Sentencing Law, enacted in 1917—and hailed at the time as a “reform”—created an experiment founded on the notion that rehabilitation of criminals can be effected in prisons through education and guidance. The experiment ended six decades later when it became clear the underlying theory was wrong.

As a general rule, though marked by exceptions, you simply can’t “teach” a cheater to be honest, a bully to be passive, a tormentor to be a nice guy.

A U.S. District Court judge of the Northern District of California remarked in a Jan. 26, 1976 opinion:

“While the indeterminate sentence law may have represented a well-intentioned, indeed enlightened, experiment in criminal sentencing when it was enacted nearly sixty years ago, it is clear, in the Court’s opinion, that the experiment has proved a failure. Others, of course, share this view; the Attorney General of California [Evelle J. Younger] has himself recently urged abolition of the indeterminate sentencing system and has stated that he will soon introduce legislation to achieve that result.”

In People v. Sutton, a Dec. 11, 1980 Court of Appeal opinion from the Fourth District’s Div. Three, Presiding Justice Robert Gardner observed:

“When, in 1976, the Legislature ended its 60-year-old romance with the Indeterminate Sentence Law, few tears were shed at the demise of that highly visionary, but woefully unsuccessful, effort at effective penology.”

As the Third District Court of Appeal recited in its Sept. 14, 1984 opinion in People v. Caddick:

“By the 1970’s, the rehabilitative model of indeterminate sentencing had been somewhat discredited.”

It quotes an article in the U.C. Davis Law Review as saying:

“[W]idespread recognition of the failure and abuses of the rehabilitative ideal was the primary factor in the dismantling of the indeterminate sentencing system.”

That dismantling was effected by the Uniform Determinate Sentencing Act, created by Senate Bill 42. It passed the Legislature on Sept. 1, 1956.

★

The next morning, the Los Angeles Times, which had once seen promise in an indeterminate sentencing scheme, reflected in an editorial that back in 1917, institution of the indeterminate sentence “was widely thought to be a major penal reform,” but that “[e]xperience did not bear out the hopes of the reformers.”

It noted that release of a prisoner “could depend on the changing philosophies of parole board members,” and declared:

“The present system is capricious. The fact that almost half of all freed convicts are back in state prisons within six years attests to the inability of the paroling authorities to judge either rehabilitation or a parolee’s chances for success on the streets.

“The fixing of sentences belongs in the courts, not only to end the uncertainty for those already behind bars but also to forewarn potential violators of the certainty of punishment.”

SB 42 was signed into law by Gov. Jerry Brown on Sept. 20, 1976, and it went into effect on July 1, 1977. Penal Code §1170 declares:

“The Legislature finds and declares that the purpose of imprisonment for crime is punishment.”

★

In 2016, §1170 was amended by Assembly Bill No. 2590 (effective Jan. 1, 2017) to read:

“The Legislature finds and declares that the purpose of sentencing is public safety achieved through punishment, rehabilitation, and restorative justice.”

While there was thus a fresh legislative endorsement of the goal of rehabilitation—a goal that was not abandoned with passage of the Determinate Sentencing Act in 1976, though a belief in its efficacy had dwindled—there was no departure from a recognition that a purpose of sentencing remains that of punishment.

Assembly Concurrent Resolution 186, proposed last year by Assembly member Sydney Kamlager, D-Culver City, sought recognition that “[m]ercy, redemption, and rehabilitation must be centered as the cornerstones of our legal system.” That proposal fizzled.

There is certainly no pronouncement by the Legislature that short sentences are the best approach to promoting a fruitful reintegration of a criminal into society, as Gascón contends, and there has been no repeal of the Three Strikes Law (though there have been modifications of it) which disincentivizes recidivism.

★

The statutorily recognized purposes of sentencing now include, along with “punishment,” rehabilitation—an ever-present goal, though seldom achieved—and “restorative justice.” Gascón has decreed that any sentence “must serve a rehabilitative or restorative purpose.”

And what is this relatively new concept of “restorative justice”?

No California statute defines it. However, Penal Code §17.5(a)(8) which lists possible types of “community-based punishments” includes: “(E) Restorative justice programs such as mandatory victim restitution and victim-offender reconciliation.”

So far as restitution is concerned, statutes require sentencing judges to order direct restitution to victims and authorize payment to a state restitution fund.

Note that Gascón puts forth, in the alternative, that a sentence “must serve a rehabilitative or restorative purpose.” In other words, if it serves a restorative purpose,” it need not serve the cause of rehabilitation. Thus, under Gascónism, if a restitution fine is imposed (conditioned, under case law, on the defendant’s ability to pay) or direct restitution is ordered, the purpose of sentencing has thus been fulfilled and, so, presumably no incarceration is needed.

Does Gascón believe that? Probably not; that is, however, what logically follows from words he has repeatedly used.

Anyway, what “restorative justice” primarily envisions is a face-to-face meeting of the culprit and the victim.

Such post-crime mediation might be suitable where the offense was a misdemeanor, conceivably in a case of a felony, especially where the defendant had enjoyed a close relationship with the victim. But is a kiss-and-make-up approach realistic in the context of violent felonies? Is it feasible to expect anything productive to ensue from a get-together of the kin or spouse of a slain loved-one and the slayer? Or a chat between a raped and beaten robbery victim and her assailant?

Common sense dictates that that “restorative justice” be quickly swept from any discussion of the primary purposes of felony sentencing. That leaves punishment and rehabilitation.

Any scheme that entails rehabilitation as the chief, if not sole, purpose of a penal system is predicated on a theory that has been broadly repudiated and has as much going for it as a proposed return to Prohibition or lobotomies, or the resumed production of the Edsel.

★

Like the flimflammer who tells a diabetic, “Buy my tonic, take it daily, and you won’t need insulin,” Gascón proclaims, in essence: “Adhere to my reforms and we can forget about sentence enhancements, strikes, LWOP, and wasting time opposing parole.”

The U.S. Supreme Court in its 2010 opinion in Graham v. Florida recited that “the goals of penal sanctions that have been recognized as legitimate”—indeed, recognized historically—are “retribution, deterrence, incapacitation, and rehabilitation.”

Retribution. Deterrence. Incapacitation. Those are accepted objectives of a penal system which Gascónism, fixating on rehabilitation, eschews.

The public’s need for the deterrent effect of established penalties for violations of penal statutes is self-evident. It cannot realistically be postulated that the “moral imperative” or the prospect of societal disapprobation are sufficient to deter killing and stealing. While prison terms do not rehabilitate, they do serve as a punishment. What penalty could be substituted? A return to chopping off the hands of thieves? Banishment to a desert island?

So far as incapacitation is concerned, a wrongdoer who is in a penal institution is not going to be inflicting harm on the general public. (Yet, Gascón has issued an edict that no parole is to be opposed by his office; normally it will be supported, and in rare cases no position will be taken.)

★

Retribution is the only one of these objectives the legitimacy of which is questioned by some.

In the 1965 California Supreme Court case of In re Estrada, Justice Raymond Peters commented that under “the best modern theories concerning the functions of punishment in criminal law,” punishment may be aimed at deterrence, incapacitation and rehabilitation, but cautioned: “There is no place in the scheme for punishment for its own sake, the product simply of vengeance or retribution.”

The definition of “retribution” was refined by then-California Supreme Court Justice Marvin Baxter (now retired) in his 2007 opinion in People v. Zambrano, terming it a penalty “exacted by the state, under controlled circumstances, and on behalf of all its members, in lieu of the right of personal retaliation”—that is, self-help.

It serves “all of its members” in the sense that where the public’s laws are violated, and the transgressor is subjected to a penalty, there is a general sense of satisfaction that justice has been done, and that those laws are being defended. Although the ancient talionic concept (“an eye for eye”) no longer has adherents, there remains a societal desire to see wrongdoers punished. That this does occur inevitably promotes among the populace a sense of security.

Too, the state is acting for victims. If, for example, the widow or widower of a murder victim (he or she also being a victim) can take solace in the fact that the killer is behind bars rather than out playing golf, that confers a benefit on a party deserving of society’s solicitude.

Although that benefit, in and of itself, cannot reasonably justify the expense to taxpayers of incarceration, full justification does come in the form of incapacitation and deterrence.

★

A criminal justice system in Los Angeles County, to work effectively, must be purged of a district attorney who is the criminal’s best friend, who seeks leniency to the point of subverting traditional prosecutorial objectives, and who, in particular, calls for supposed “reforms” that are predicated on the disproven notion that rehabilitation works.

Those who, in the late 1800s and early 1900s, supported the seeming “reform” of indeterminate sentencing—in an era of callous, even brutal, treatment of prisoners—were persons who found hope in a theory, put forth by experts, that criminals could be set on the path to rectitude through a benign method: education. Idealists who promoted the experiment that came to be launched can hardly be faulted because it failed.

But those who—most prominently Gascón—would today presume to call for “rehabilitation” as the foundation of the sentencing system without acknowledging that the idea was tried and proved to be a dud, and can point to no reason why it would be different now, are, plainly, dishonest.

Copyright 2021, Metropolitan News Company