Wednesday, January 20, 2021

Special Section

PERSONALITY PROFILE:

JOHN LEROY MORIARITY

Music and Military, Law Enforcement and Reagan, Are Trial Lawyer’s Interests

By Sandra Hong

|

A |

t the annual convention of the California Trial Lawyers Association (now known as Consumer Attorneys of California) in 1973, Los Angeles chapter President Stanley Jacobs announced that John L. Moriarity had tried more personal injury cases to verdict in the past year than any other lawyer in California. And Moriarity had been in law practice for only a dozen years.

That distinction—among other career milestones—has prompted references to him as “the dean of San Fernando practitioners.”

Moriarity insists that it’s simply a nod to his sheer longevity.

It’s “because I’m the oldest, that’s all,” the 88-year-old says, chuckling.

Yet before he dedicated more than a half-century to law practice in the same city he was born and raised, there was a two-year stint in Texas, a gig alongside Louis Armstrong, and a deep appreciation for music and history.

“Music and the military have been a very big part of my career,” he muses.

Graduation Day

To hear Moriarity tell it, his law career was built on early inspiration and a few lucky coincidences. He recounts the day he graduated from UCLA School of Law in 1960.

|

|

|

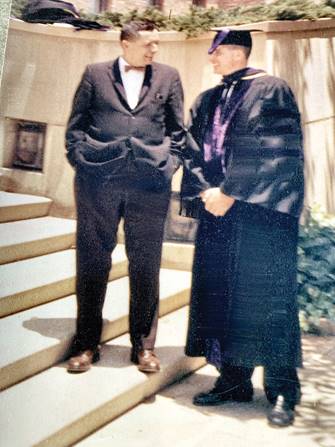

Moriarity is seen at graduation from UCLA Law School with his favorite professor, Edgar Allan Jones Jr., who portrayed a judge on ABC television’s “Day in Court” from 1958-64. |

“I graduated from UCLA at 11 o’clock and got a job at the state attorney’s office at 2 o’clock,” he says. Before even passing the bar, he started work that same afternoon as a “student attorney” at the California Department of Transportation.

“I was making $30 more a month than a real-life entry level attorney at the AG’s office,” he remembers.

It wasn’t the only offer he had. There was an opportunity at the FBI, but the pay was lower—only $7,000 a year.

A fellow graduate, one year ahead of Moriarity, Irvin Schulman, ran into him after the graduation ceremony and told him about the student attorney job at Caltrans. It would lay the groundwork for his career as a personal injury attorney.

At the time, the courts were chipping away at sovereign immunity, Moriarity says, pointing, in particular, to the 1961 California Supreme Court opinion in Muskopf v. Corning Hospital District which ended immunity for hospital districts.

“So, all of a sudden, they had to start worrying about personal injury cases” at Caltrans, he says.

After-School Jobs

In high school, he drove a police ambulance for a year, and during law school, he worked as an insurance adjuster specializing in bodily injury claims, Moriarity recounts, saying:

“So I knew just enough about personal injury to get myself in trouble.”

He adds, however:

“But I knew more than the 32 other attorneys because they only did condemnation work.”

He worked for Caltrans for three years, the required commitment for a student attorney. During that time, Moriarity was also working as an adjuster for Farmers Insurance and was slowly building his own practice, taking medical malpractice defense cases on the side.

His interest in law traces back to when he was just four years old. His parents were divorcing, and his mother hired a lawyer, Charles Cook, to represent her. Moriarity remembers taking an interest in the way Cook did his work.

“Watching him at the old stone courthouse, for some reason,” he says, the idea of becoming a lawyer himself, “caught on,”

By the fifth grade, he recounts, he decided he was going to be a lawyer.

Music and the Military

After he reached high school in Van Nuys, he decided to enter the Army Reserve in his junior year, and was eventually called for basic training in February 1954, less than a year after an armistice ended combat in the Korean War. In the middle of his sophomore year at UCLA, Moriarity abruptly moved from a campus dormitory to barracks at Fort Ord near Monterey.

“After you finish the basic course, you’re told you have three choices,” Moriarity says. “My first choice was to go with a judge advocate general course” since he knew he wanted to pursue a career in law.

His second choice was to stay in the artillery and climb the ranks to staff sergeant.

Third was to join the Sixth Army Band. Moriarity had played cello and trombone in the orchestra and band at Van Nuys High School.

“Interesting thing was—which was typical of the U.S. Army—they sent me to the Army medical school in Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas, keeping in mind my three requests,” he says.

He adds that he nonetheless “ended up having an absolutely wonderful time for two years in San Antonio.”

Shortly after arriving in Texas, Moriarity organized a dance band he called the Night Owls. He also struck up what would become a lifelong friendship with Don Carey, who arrived at Fort Sam Houston having just finished a music degree at the University of Kansas, and joined Moriarity’s band as a piano player.

“We played so much in San Antonio and so many other places,” Carey recalls from his home in Missoula, where he retired as a professor of music at the University of Montana.

Carey remembers how weekends were filled with late-night gigs that wouldn’t allow for much sleep. He also recalls Moriarity’s “fierce amateurism” as a musician.

“He was a driven musical amateur and still is,” Carey says. “He really loves it.

“He not only wants to listen to it, but also make it and take part in it. He’s always been that way.”

As for Moriarity’s dance band, Carey says:

“It was not just a fun thing to do for him. He was really immersed. And of course, that really rubbed off on all the members of the band.”

Moriarity made sure the Night Owls kept up a rigorous performance schedule.

“We played seven nights a week and sometimes Sunday afternoon at various private clubs, and in San Antonio we had 10 officer clubs or enlisted clubs that we played in,” Moriarity says.

Armstrong, Christy

He recounts a gig the Night Owls played with singer June Christy, along with the band’s brush with Louis Armstrong.

“It was a package deal, and we went in with him,” Moriarity says about the night they played in the same venue as the jazz legend. “He was playing in one ballroom and we were playing in another one,” he explains.

Moriarity kept up the Night Owls after he returned to Los Angeles in 1956. In Los Angeles, his bandmates were studio musicians and headliners in the Hollywood scene.

The lawyer confesses that he hasn’t picked up an instrument since law school, but Carey says Moriarity’s appetite for music hasn’t waned since their military days. When the two get together, Moriarity is sure to pull out records of all-male quartets like The Hi-Lo’s and The Four Freshmen.

“We’ll just sit and listen to them,” Carey says. “For a lawyer, he’s really interested in music. He takes it very seriously. If you look at the pictures he has hanging in his office, you’ll see he’s got pictures of dance bands and girls from that time singing.”

Once back at UCLA, Moriarity picked up his studies in U.S. and British history.

“If I hadn’t gotten into law school, I would have gotten a PhD in history,” Moriarity says. “I absolutely loved history.”

But he did get into law school, graduated, then passed the California bar exam in 1961.

Lawyer’s Cases

The long career in personal injury law that ensued has provided Moriarity plenty of tales to spin, if not in front of a classroom. He’s prevailed in cases that shaped standards of care for public entities. One case involved a neglected center-lane barrier on Interstate 5, where a vehicle crossed into the opposite lane and caused a head-on collision.

“The case made it to the Court of Appeals, which made it very clear that Caltrans had to maintain the barriers,” Moriarity says.

|

|

|

Moriarity is pictured at an Army ball with fiancée Kelley Nelson. |

Moriarity also took on a medical malpractice case involving a doctor in Lancaster whose negligence caused the death of a young patient.

The case was the kind a plaintiff’s injury lawyer dreams of, Moriarity says, with a doctor defendant who fell short of the “Doctor Welby” stereotype, a reference to the popular 1970s TV show featuring a kindly Dr. Marcus Welby, portrayed by Robert Young.

“It was a classic example of where a plaintiff can win a case, where you can show the doctor was a thief, a fraud, a bad guy,” Moriarity says.

Moriarity was able to show the doctor altered the patient’s medical records to cover up any signs of wrongdoing. The insurance company only had the records that had been scrubbed clean.

“But I had the bad ones, the dirty ones,” Moriarty says. “And once they found that out, we were able to recover in excess of $1 million.”

Another slam-dunk case was against a general surgeon at Kaiser against whom Moriarity brought suit for a client. The defendant had cleaned up the patient records, but, again, Moriarity got his hands on the original files, showing negligence.

“Those are the good cases where you recover damages” which keeps the office “doors open and pay for the overhead for the ones that come back snake eyes,” he says.

Yet, Moriarity, reflects, the highs and lows of plaintiffs’ personal injury work isn’t for everyone.

“It’s become, more and more, so difficult, especially in the medical malpractice field,” he remarks. “The defense has so much money they can just swamp you.

“I have a case against Johnson & Johnson right now and keeping up with them is really something. They have billions of dollars and here I am trying to foot the bill to keep up with them.”

Another challenge is keeping up with health care lobbyists in Sacramento. Moriarity notes how the $250,000 cap on non-economic damages in medical malpractice lawsuits hasn’t changed since the Medical Injury Compensation Reform Act was passed in 1975.

“Now why is that?” he asks, answering:

“The reason, very simply, is the medical profession.”

Powerful health care lobbying interests, including the American Medical Association and California Medical Association, “have bought the Legislature” with campaign contributions, he asserts. Given that “California trial lawyers have never been able to match what the AMA and CMA can spend in California,” the lawyer remarks, change is not likely.

Political Aspirations

In 1994, after 30 years of practicing law, Moriarity ran for an open seat on the Los Angeles Superior Court. He says of his motivation to run:

“Being a trial attorney, I experienced really wonderful judges—and some men and women that should never have become judges. I thought I could make a difference.”

Despite support from major law enforcement departments, unions and newspapers, Moriarty lost in a tight runoff election against an assemblyman.

Terry Friedman was known as having “the most liberal voting record of any assemblyperson at the time,” Moriarity remarks, “even more liberal than [actress] Jane Fonda’s husband.” Her husband, now deceased, Was Tom Hayden, who was by then a former Assembly member and a member of the state Senate.

Moriarity’s campaign, promoting law and order, “was kind of a mistake,” he says, commenting:

“It would be the same as running today in a socialist county, city, or state as someone who backs the police department.”

Voters here ultimately decide against a pro-law enforcement candidate, Moriarity laments. He says the state’s political dynamics deterred him from making another attempt at running for elected office.

“Look what just happened to our wonderful district attorney, Jackie Lacey,” Moriarity says.

Lacey served two terms as Los Angeles County district attorney before being unseated in the Nov. 3 election by challenger George Gascón, who campaigned on promises of criminal justice reform.

Lacey’s immediate predecessor, Steve Cooley, recalls first crossing paths with Moriarity around the time he ran for judge.

“He worked hard,” Cooley says about Moriarity’s campaign, which, despite worthy efforts, lost to an adversary with “significant political clout.”

Cooley credits Moriarity with having “good, solid values, the kind that maybe we don’t see as much today as we all would like,” describing Moriarity as “patriotic” and “a thoughtful conservative.”

And while Moriarity didn’t end up serving in an elected office, his contributions through community and professional organizations can’t be overlooked, Cooley adds, remarking:

“He belongs to more groups than anyone I know. He contributes to all the groups with his time, presence, and loyalty.”

McDonnell Comments

Former Los Angeles County Sheriff Jim McDonnell echoes similar sentiments about Moriarity’s civic involvement, particularly in support of law enforcement.

|

|

|

A bronze statue of President Ronald Reagan is seen behind a delegation from the Reagan Library which brought the work in 2019 to Berlin, where Reagan made a speech in 1987 at the Brandenburg Gate urging that the wall dividing East and West Germany be torn down. Moriarity, front center, led the delegation. The unveiling of the statue took place on Nov. 8; the following day marked the 30th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall. |

“He’s a guy who’s known as always there in support of a good cause and somebody who’s willing to get involved to benefit the community,” McDonnell says. McDonnell observes that Moriarity’s past aspiration of serving in elected office would not come as a surprise, considering his passion for bridging relations between police and the community.

Plus, McDonnell says, “people enjoy being around him, and it shows.”

Lacey also highlights Moriarity’s affable nature, saying:

“He is outspoken, quick-witted, and friendly. He always greeted me with a strong handshake and a smile. He is a generous person and a fierce advocate for the underdog.”

Moriarity acknowledges a seemingly endless list of civic organizations and nonprofit boards he’s been a part of, among which include the Los Angeles Police Reserve Foundation. Foundation President Karla Ahmanson calls Moriarity a “good, old-fashioned gentleman” who has helped the foundation raise money and supported various programs to recruit reserve police officers.

“There’s really not many like him anymore,” she says.

Through his work with the police foundation, Moriarity met his fiancée, Kelley Nelson, three years ago.

Moriarity had been married for almost 50 years to Maria Ann Moriarity, who died of cancer on Nov. 17, 2009. They had six children: Donald (named after Moriarity’s Night Owl bandmate Don Carey), Lloyd, Lynda, Robert, Jack, and Douglas.

Not one of them showed the slightest bit of interest in becoming a lawyer, he says, but adds:

“Well, I got two of them into the military but couldn’t get any of them thinking about law or being a peace officer.”

Reagan’s Speech

Near the end of 2019, Moriarity helped deliver a life-sized bronze statue of Ronald Reagan to the U.S. Embassy in Berlin. The embassy is located next to the Brandenburg Gate, where Reagan gave a monumental speech as president.

Reagan’s bronze likeness was a gift from the Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation and Institute, which has dispatched groups to locations around the world where Reagan made significant addresses.

“I led the group to Berlin, where Reagan had asked secretary Gorbachev to take down the wall—which to me was one of his most lasting speeches,” Moriarity says.

Reagan stood at the Brandenburg Gate on June 12, 1987. The concrete barrier, erected in 1961, separating east and west Berlin, was visible behind him. Directing remarks to Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, he said:

“General Secretary Gorbachev, if you seek peace, if you seek prosperity for the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, if you seek liberalization, come here to this gate.”

Following that were his famous words:

“Mr. Gorbachev, open this gate! Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!”

The Reagan Foundation’s 2019 entourage to Berlin included Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, Moriarity says, as well as foundation Executive Director John Heubusch.

The foundation sustains the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library and Museum in Simi Valley.

“You walk in there and you’ll see my name on the wall in big gold letters,” he says.

“When we started trying to build the library in 1988, we wanted to build the library on the grounds of Stanford to be close to the Hoover Institution, but the socialist professors at Stanford would have nothing to do with us,” Moriarity remarks.

Upon walking into the library, a visitor will hear and see Reagan making his “A Time for Choosing” speech. A video monitor plays the speech on a loop.

That speech has particular significance for Moriarity.

In the Oct. 27, 1964 pre-recorded televised talk—which would propel the actor onto the national political stag—Reagan made a case for the election of the Republican Party’s presidential nominee, U.S. Sen. Barry Goldwater, R-Ariz. Echoing themes of the campaign, Reagan called for “peace and prosperity” through tax cuts and pared-down government, and warned of the perils of socialism.

“It turned me around completely,” Moriarity, then a Democrat, says.

Reagan starts the speech by sharing that he had been a lifelong Democrat until switching course, and goes on to say:

“You and I are told increasingly we have to choose between a left or right. Well I’d like to suggest there is no such thing as a left or right. There’s only an up or down….”

“Up” is individual freedom and manifest destiny, Reagan says; “down” is characterized as “the ant heap of totalitarianism.”

Moriarity says the philosophy still rings true to him 56 years later.

“I’m a strong believer in the free-enterprise system,” he says. He points to founders of business empires such as Marriott hotels and Carl’s Jr. as proof that Reagan’s vision of American exceptionalism remains the country’s answer to peace and prosperity.

“That’s how these people got to where they are—they started from nothing but have been able to thrive,” he comments.

As for Moriarity, he continues to look “up” in his career. He relates that he has no plans to retire.

“I enjoy what I do,” he says.

Comments:

It is with honor and pride to recognize John Moriarity as the Metropolitan News-Enterprise 2020 Person of the Year. John’s reputation as the “Dean of San Fernando Valley practitioners” is well-founded as he has shown his accomplished skills as a trial litigator for many decades. His service to each client has been in the highest tradition of professionalism and dedication.

As one of this nation’s proudest patriots, Mr. Moriarity has demonstrated his commitment to men and women in our armed forces and here in the Homeland through his financial support as well as providing his counsel as a board member on the Los Angeles Police Reserve Foundation. It is in this latter role that John has most impacted the Los Angeles Police Department. Mr. Moriarity has strived for years to help support members of the police reserves as they volunteer their time in the service to the people of Los Angeles.

In closing, the Los Angeles Police Department congratulates John Moriarity as the Metropolitan News-Enterprise 2020 Person of the Year and wishes him continued good health and success in the years ahead.

—MICHEL R. MOORE

Chief of Police

Los Angeles Police Department

Colonel John L. Moriarity is many things, but anyone who has spent even a few minutes with him likely knows that he is a patriot of the first order. That could mean different things to different people perhaps, but in John’s case, that means he loves his country far more than most, and does all that he can to honor it, and make it even better. He values highly his extended time in the military service.

John is a member of more organizations than one would ever imagine—and he is active in each of them. He attends more events of every description than seems possible. He is an encourager extraordinaire. He puts people together who have a common interest of some sort.

Music is, and has always been, highly important to him—both as a performer and as a listener. The fine arts, in their different forms, constantly beckon him to their happenings.

He has long been a devoted advocate for Pepperdine University, and particularly its Caruso School of Law, and is responsible for encouraging a number of excellent students to attend.

For in excess of four decades, he has supported the Law School, and has served on its Board of Visitors, and now its successor organization, the Board of Advisors. He and his late wife established the Colonel John L. and Maria Moriarity First-Year Moot Court Competition.

John is a most successful trial lawyer, and an indefatigable advocate for his clients.

It is widely known that John is a staunch supporter of law enforcement, and Los Angeles sheriffs and police chiefs over time are his close friends. Speaking of friends, John makes them easily and constantly.

Countless organizations of widely varying description and purpose are better, and more effective, because of Colonel John L. Moriarity.

—RONALD F. PHILLIPS

Senior Vice Chancellor,

Caruso School of Law Dean Emeritus,

Pepperdine University

Copyright 2021, Metropolitan News Company