Page 1

Court of Appeal:

‘Irrevocably’ Was Ambiguous Where Duration Not Stated

Justice Baker Says Agreement, Signed by Performer Known As ‘Sly Stone,’ Taken in Context, Is Not Certain

|

|

|

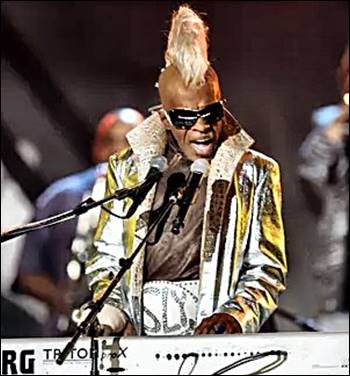

In this Feb. 8, 2006 file photo, Sly Stone from the group Sly and the Family Stone performs at the Grammy Awards in Los Angeles. The Court of Appeal for this district yesterday held that a 1976 contract between the performer and his manager “irrevocably” assigning royalties to the manager was ambiguous and the meaning must be determined by a trier of facts, reversing a summary adjudication. |

By a MetNews Staff Writer

“Irrevocably” doesn’t necessarily mean permanently, Div. Five of this district’s Court of Appeal held yesterday in a case involving entitlement to royalty payments for performances from 1976 through 2009 by Sly Stone, lead performer for the funk band “Sly and the Family Stone,” which enjoyed popularity in the 1960s.

The erstwhile performer—whose actual name is Sylvester Stewart—was not a part to the appeal.

The plaintiff in the case is Virginia Pope, successor to Ken Roberts, now deceased, who was Stewart’s manager. A document signed by Stewart and Roberts in 1976 recited that that Stewart ““unconditionally, irrevocably and absolutely assigns to Ken Roberts and/or Ken Roberts Enterprises, Inc. as the Assignee and/or Judgment Creditor of Sylvester Stewart...any and all” royalty payments” from Broadcast Music Inc. (“BMI”).

BMI collects license fees from businesses that use music and distribute funds—$1.2 billion in 2019—to composers and performers, who have assigned their rights to BMI.

Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Mark V. Mooney summarily adjudicated Pope’s ownership of the royalties, but also summarily adjudicated Pope’s cause of action for conversion in favor of defendants Even St. Productions Ltd., Stewart’s ex-manager Gerald Goldstein, and attorney Glenn Stone.

In yesterday’s unpublished opinion, Acting Presiding Justice Lamar Baker said Mooney erred in granting summary adjudication to Pope on her cause of action for declaratory relief. “In isolation, the modifier ‘irrevocably’ ” in the 1976 agreement between Stewart and Roberts “could be read to mean the assignment was not revocable in perpetuity—but that is not the only possible meaning,” Baker said, explaining:

“Rather, when understood in context of the document’s own characterization of Stewart as a judgment creditor and Roberts’s later sworn declaration that the assignment was given ‘as security for the payment of loans previously made to [him]’, the 1976 Assignment is ambiguous about the duration in which it would be irrevocable—namely, in perpetuity or only until Stewart’s existing debt to Roberts was repaid. Trial of the declaratory relief cause of action is accordingly necessary to decide that issue, i.e., whether Stewart or Roberts held the contractual right to royalty payments at the time of Stewart’s (purported) assignment of those rights to the Even St. Parties in 1989.”

Under the 1989 agreement, Stewart became an employee of Even Street, controlled by Goldstein, Stone, and one other who was not a party to the appeal decided yesterday. That agreement included an assignment of Stewart’s right to royalties to Even Street.

Changed Instructions

BMI initially paid the royalties, in conformity with the 1976 agreement to Roberts, then, under later instructions, to Roberts-Majoken Inc., which Roberts had formed. As of 1980, BMI adhered to a directive from the Internal Revenue Service to provide the funds to it, to satisfy back taxes owed by Stewart, until 1996, when an attorney for Even St. negotiated a settlement with the IRS and its lien was lifted. That year, “Goldstein-Majoken” was formed by principals of Even St. and BMI was asked to send royalties to that entity, at Even Street’s address. (Majoken was the surname of Roberts’s parents, with whom Goldstein and Stone had no business relationship.)

In yesterday’s decision, Baker declared Mooney to have been correct in summarily adjudicating Pope’s cause of action for conversion in favor of the defendants. He wrote:

“Roberts did not own the rights for the Sly Stone musical performances in question or the royalties BMI collected as the owner of those rights. Instead, Roberts had a contractual right to payment of royalties (at least for some period of time) that derived from Stewart’s original decision to grant to BMI ‘[a]ll the rights that [he] own[ed]’ and the 1976 Assignment from Stewart to Roberts. Roberts therefore lacked the ownership interest in property that a conversion claim requires.”

Fraud Alleged

Baker went on to say:

“Pope also asserts the Even St. Parties ‘employed a fraudulent scheme to steal the royalties’ that should have entitled Roberts to an equitable lien or made the Even St. Parties an involuntary trustee. But equitable liens or involuntary trusts are merely remedies, and remedies depend on the existence of a viable cause of action—which is lacking here for the reasons already given. A conversion claim is not made viable by merely presupposing fraud and usurpation of damages from that fraud.”

Roberts-Majoken brought a cross-complaint against Even St. and its principals for constructive fraud and money had and received. Mooney, after a bench trial, ruled in favor of the defendants on both causes of action.

Judge ‘Half Right’

The judge was “only half right,” Baker said. His opinion reverses the judgment as to the cause of action for money had and received and remands for a new trial.

Constructive fraud requires a fiduciary relationship, he said, noting that “[T]here was no proof at trial that any of the Even St. Parties had a fiduciary relationship (or any relationship, really) with Roberts Majoken.”

With respect to the cause of action for money had and received, he reasoned:

“There was ample evidence at trial that would support a conclusion the Even St. Parties did receive money (royalty payments from BMI) belonging to another and that should, in equity and good conscience, be returned to the rightful recipient. At the same time, substantial evidence does support the trial court’s determination that Roberts Majoken—as distinguished from Roberts—was not the rightful recipient of at least some of the royalty payments: in 1992, Roberts Majoken was dissolved by the State of New York and Roberts transferred the royalty payment rights he in 1979 assigned to Roberts Majoken back to himself as an individual.”

Amendment Sought

He continued:

“The problem for the Even St. Parties, however, is Pope’s counterargument: the trial court erred by not permitting her—at the end of the bench trial on Roberts Majoken s cross-complaint and having foreshadowed the request before trial—to add Pope (as Roberts’s successor) as a plaintiff asserting the same money had and received claim. Such an amendment is authorized under Code of Civil Procedure section 473, subdivision (a) when in furtherance of justice, and whether to permit the amendment is committed to the trial court’s discretion.”

Mooney abused his discretion in not permitting the amendment, he declared.

The case is Pope v. Even St. Productions, B275199.

Attorneys on appeal were Jay M. Spillane for Pope and Roberts-Majoken; Joseph S. Klapach of Klapach & Klapach and Gregory Bodell of Kozberg & Bodell for Goldstein and Stone; and David N. Tarlow of Ervin Cohen & Jessup for Even St. Productions, Ltd. and Majoken, Inc.

In a July 25, 2016 unpublished opinion by Baker, Div. Five reversed a judgment in favor of BMI in an action brought by Roberts because the jury was not instructed that it was to treat as conclusively proved matters that BMI had admitted in responding to requests for admission.

Copyright 2021, Metropolitan News Company