Page 1

California Supreme Court:

Jury Unanimity Not Required on Aggravating Circumstances

From staff and wire service reports

|

|

|

—AP This 2010 file photo shows the death chamber of the new lethal injection facility at San Quentin State Prison. The California Supreme Court yesterday rejected an attempt to make it harder to impose the death penalty. It ruled in favor of the current system under which jurors need not unanimously agree on aggravating factors used to justify the punishment. |

The California Supreme Court yesterday rejected an attempt to make it harder to impose the death penalty, ruling in favor of the current system under which jurors need not unanimously agree on aggravating factors used to justify the punishment and need not find allegations to be true based on a reasonable doubt standard.

While a jury must unanimously agree to impose a death sentence, and to do so must decide that aggravating factors outweigh mitigating circumstances, jurors determining guilt or innocence, the court said in a 7-0 decision, do not have to unanimously agree on each specific aggravating factor.

The automatic appeal comes in the case of Donte Lamont McDaniel, convicted in the courtroom of then-Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Robert J. Perry, who retired on March 5. Jurors at the guilt phase found true the special circumstance of multiple murders and found true the allegations of intentional discharge and use of a firearm, intentional discharge resulting in great bodily injury and death, and commission of the offense for the benefit of, at the direction of, and in association with, a criminal street gang.

McDaniel was sentenced to death in 2009 for the murders of 33-year-old George Brooks and 52-year-old Annette Anderson and two counts of attempted murder on behalf of the Bounty Hunter Bloods street gang. The court upheld his conviction and sentence.

Justice Goodwin Liu wrote the opinion—one which, had the decision been in accord with the position of the appellant, could have undermined the death sentences of the most populous state’s nearly 700 condemned prisoners.

McDaniel relied on Penal Code §1042—which provides, “Issues of fact shall be tried in the manner provided in Article I, Section 16 of the Constitution of this state”—and on that constitutional provision, which declares:

“Trial by jury is an inviolate right and shall be secured to all, but in a civil cause three-fourths of the jury may render a verdict. A jury may be waived in a criminal cause by the consent of both parties expressed in open court by the defendant and the defendant’s counsel.”

Together, these provisions require jury unanimity as to aggravating circumstances, McDaniel insisted.

“We have previously held that jury unanimity on the existence of aggravating circumstances is not required under the state Constitution,” Liu said, adding:

“McDaniel does not persuade us that there is an independent state law principle grounded in Article I, Section 16 requiring unanimity among the penalty jury in order to find the existence of aggravating circumstances in the face of disputed evidence.”

Sympathy Expressed

But the jurist indicated a sympathy for the proposition that a consideration be lent a change on the law. He wrote:

“[T]he Attorney General has acknowledged that requiring the penalty jury to ‘unanimously determine beyond a reasonable doubt factually disputed aggravating evidence and the ultimate penalty verdict...would improve our system of capital punishment and make it even more reliable,’ and that statutory reforms ‘deserve serious consideration.’ Nevertheless, to date our Legislature and electorate have not imposed such requirements by statute, and the out-of-state holdings above are based at least in part on due process or Eighth Amendment grounds. McDaniel does not ask us to reconsider our precedent that has concluded otherwise as a matter of due process.

“In sum, having examined our case law and relevant history, we are unable to infer from the jury trial guarantee in article I, section 16 of the California Constitution or Penal Code section 1042 a requirement of certainty beyond a reasonable doubt for the ultimate penalty verdict.”

Reaction to Decision

Criminal Justice Legal Foundation Legal Director Kent Scheidegger, who wrote a brief supporting the death penalty, commented:

“I am pleased to see that the California Supreme Court has unanimously rejected a call to overturn decades of clear precedent.”

He also remarked:

“Today’s decision upholds the law as written and preserves the sentences of California’s worst murderers, which certainly includes Donte Lamont McDaniel,”

Gov. Gavin Newsom was one of those seeking stricter standards when he took the unprecedented step of filing a brief arguing that current practices spur racial discrimination. Newsom’s brief, drafted by University of California, Berkeley School of Law Professors Erwin Chemerinsky and Elisabeth Semel, tracked the utterances of other critics who contend the death penalty process is inherently racist because Black people are disproportionately excluded from juries in capital cases.

But those more sweeping objections “do not bear directly on the specific state law questions before us,” Liu wrote.

Nor did the court find evidence of prosecutorial basis against Black jurors in the case.

|

|

|

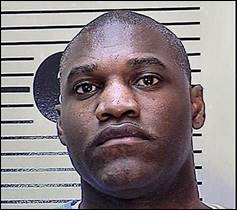

DONTE LAMONT Mc DANIEL Condemned killer |

Semel’s Reaction

Semel, who is co-director of the UC Berkeley Death Penalty Clinic, voiced this reaction to the opinion:

“It doesn’t change the fact that the death penalty system in California does discriminate against people of color, particularly Black defendants. And there’s ample data to demonstrate that.”

Newsom spokeswoman Erin Mellon said the court “missed an opportunity to fix one of the many flaws in California’s death penalty.” Executions are irreversible and the process discriminates not only on race but against those who are poor or mentally ill, she said.

An amicus curiae brief was also filed on behalf by a small group of district attorneys, including Los Angeles County’s chief prosecutor George Gascón, represented by Steven L. Mayer of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer. It was also signed by the district attorneys of Contra Costa, San Francisco, Santa Clara, and San Joaquin counties, and by former Los Angeles County District Attorney Gil Garcetti.

Garcetti was represented by Natasha Minsker, formerly the death penalty policy director of the ACLU of Northern California.

Concurring Opinion

Liu also wrote a 30-page opinion in which he argued the state’s death penalty process could be deemed unconstitutional under a legal argument not currently before the court.

“Over the years, this court has repeatedly rejected the claim that California’s death penalty scheme violates the jury trial right guaranteed by the Sixth Amendment to the United States Constitution,” he wrote, expressing the view that such a violation should be recognized. He explained:

“…Suppose the prosecution introduces evidence of three prior criminal acts (A, B, and C). Some jurors may find that A was proven beyond a reasonable doubt, but not B and C; other jurors may find B proven, but not A and C; others may find C proven, but not A and B; and still others may find none proven at all and instead find some other circumstance to be aggravating. Or the jurors may find various prior crimes proven beyond a reasonable doubt but differ as to which one or ones are aggravating….Our capital sentencing scheme allows the penalty jury to render a death verdict in these circumstances. But I am doubtful the Sixth Amendment does.”

He added:

“There is a world of difference between a unanimous jury finding of an aggravating circumstance and the smorgasbord approach that our capital sentencing scheme allows. Given the stakes for capital defendants, the prosecution, and the justice system, I urge this court, as well as other responsible officials sworn to uphold the Constitution, to revisit this issue at an appropriate time.”

The case is People v. McDaniel, 2021 S.O.S. 4768.

Of 1,077 death sentences imposed since 1978 in California, 230—more than 1 in 5—have been reversed by either the California Supreme Court or a federal court, according to a March report by the Office of the State Public Defender titled “California’s Broken Death Penalty.”

Copyright 2021, Metropolitan News Company