Monday, June 22, 2020

Page 1

Class Action Can’t Be Based on Scientific Notion That Product Could Cause Harm—Ninth Circuit

Opinion Says It’s Not Enough for Plaintiffs to Contend That Purchases Would Not Have Been Made If the Manufacturer Had Divulged Risks; Actual Harm From Use of Product Must Be Alleged

By a MetNews Staff Writer

|

|

|

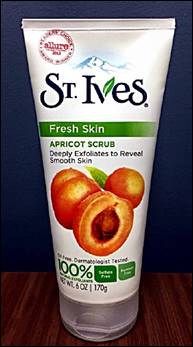

Above is a photo of a product, declared in a District Court pleading to be worthless, as depicted in the complaint. The Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals has affirmed summary judgment in favor of the manufacturer. |

Two women who say they used a facial scrub and would not have purchased it had they known that it causes “micro-tears” in the skin which, they assert, is now shown by scientific findings, have no personal claims against the manufacturer, Unilever, absent evidence of harm to themselves from use of the product, and have no cognizable class claims, the Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals has held.

Thursday’s memorandum opinion upholds a summary judgment granted on Dec. 17, 2018, to Unilever, an international manufacturing giant, by District Court Andrew J. Guilford of the Central District of California.

The plaintiffs, Kaylee Browning—a former California resident, now living in Arizona, who purchased Unilever’s St. Ives Apricot Scrub while in this state—and Sarah Basile, a denizen of New York, sued on the basis of recent revelations about the product. Their District Court complaint asserts that “St. Ives is unfit to be sold or used as a facial scrub” and “is completely worthless.”

Unilever was derelict, they contend, in failing to disclose the drawbacks inherent in using its scrub.

Potential Ill-Effects

The pleading, citing studies, says:

“Unfortunately for consumers, use of St. Ives as a facial exfoliant leads to long-term skin damage that greatly outweighs any potential benefits the product may provide. St. Ives’ primary exfoliating ingredient is crushed walnut shell, which has jagged edges that cause micro-tears in the skin when used in a scrub. While this damage may not be immediately noticeable to the naked eye, it nonetheless leads to acne, infection and wrinkles.”

In opposing summary judgment, Browning and Basile relied on a declaration by a Florida dermatologist, Mark Nestor, who opined that “use of St. Ives as directed leads to facial skin irritation and impaired barrier function” and other potential medical problems.

District Court’s View

Guilford declared that Browning and Basile “haven’t provided sufficient evidence of a safety hazard or product defect that Defendant was required to disclose” and that their “allegations are too generalized and conjectural to survive summary judgment.”

Assailing their fitness to represent a class, he said:

“Browning and Basile are asymptomatic class representatives. Even if the Court found there was a genuine dispute of fact regarding the safety hazard created by the walnut shell powder in St. Ives, it does not appear to have afflicted Browning or Basile….Browning and Basile don’t claim they suffered from micro-tears, infection, or other physical ailments when they used St. Ives….At best, Plaintiffs assume they suffered from micro-tears which they could neither see nor feel.”

Ninth Circuit Opinion

The Ninth Circuit on Thursday expressed agreement, saying:

“Plaintiffs provided no summary judgment evidence linking ‘micro-tears’ caused by Unilever’s facial scrubs to any concrete injuries. Dr. Nestor’s summary judgment declaration opined only that an impaired [outer layer of the skin] ‘can increase chances’ of a host of recognized long-term health risks, but he was unable to observe or quantify any of those risks in his two-week study. Moreover, Plaintiffs used the products for years and showed no symptoms of the ‘dry irritated skin or infections’ that Dr. Nestor warned could be caused by micro-tears.”

The opinion says that the plaintiffs’ “failure to present summary judgment evidence linking use of the product to actual injury undermines their fraudulent omission theories” and finds no fault with Guilford’s rejection of other theories.

The case is Browning v. Unilever United States, Inc., 19-55078.

Copyright 2020, Metropolitan News Company