Tuesday, March 17, 2020

Page 1

Ninth Circuit:

Suit Against Disney for Character-Theft Was Properly Axed

By a MetNews Staff Writer

|

|

|

|

Above are “Moodsters,” created by Denise Daniels. |

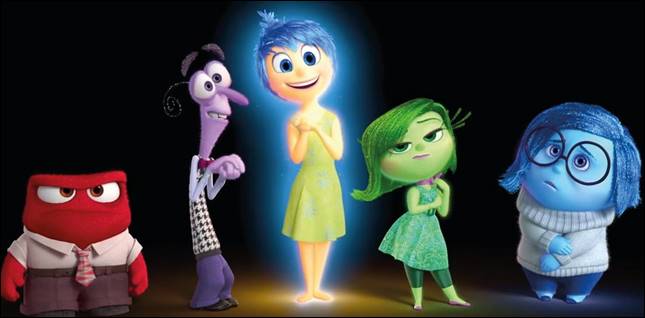

Walt Disney characters are depicted which, the Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals held yesterday, do not infringe on the Moodsters. |

The Walt Disney Company’s five anthropomorphized characters each representing a human emotion, depicted in the 2015 motion picture “Inside Out,” do not infringe upon five characters of the same nature developed by a woman 10 years earlier, the Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals held yesterday.

The plaintiff’s characters are not “sufficiently delineated” to warrant protection, Judge M. Margaret McKeown said, writing for a three-judge panel.

Denise Daniels and her company, The Moodsters Company, sued the entertainment giant over an alleged pilfering of the characters she created in 2005 and depicted in “The Moodsters Bible,” which she distributed to media executives—including those at Disney—in hopes they would be utilized in commercial endeavors, with recompense to her.

Since then, she made a pilot for a television series utilizing the characters and used them in books and toys which were sold by retailers.

Similar Emotions Depicted

Each of the “Moodsters” is a different color and each represents a different emotion, as do the five characters in the Disney movie. Emotions symbolized by each set of characters include fear, sadness and anger; one Moodster signifies “happiness” while a Disney character stands for “joy.”

The fifth emotion represented by a Moodster is love, while the fifth Disney character embodies disgust.

Yesterday’s decision affirms the dismissal of the action, with prejudice, by District Court Judge Philip S. Gutierrez of the Central District of California. McKeown wrote:

“Literary and graphic characters—from James Bond to the Batmobile—capture our creative imagination. These characters also may enjoy copyright protection, subject to certain limitations. Here we consider whether certain anthropomorphized characters representing human emotions qualify for copyright protection. They do not.”

Second Test

She said that while Daniels’s characters meet the first test for protectability—having “physical as well as conceptual qualities”—they do not meet the second: being “sufficiently delineated to be recognizable as the same character whenever it appears” and “displaying “consistent, identifiable character traits and attributes.” The jurist wrote:

“Consistently recognizable characters like Godzilla or James Bond, whose physical characteristics may change over various iterations, but who maintain consistent and identifiable character traits and attributes across various productions and adaptations, meet the test….By contrast, a character that lacks a core set of consistent and identifiable character traits and attributes is not protectable, because that character is not immediately recognizable as the same character whenever it appears.”

She noted that neither colors nor emotions can be copyrighted and that the names and physical attributes of the characters continually change.

McKeown added that the characters do not meet the third test for protectability: they are not “especially distinctive” and lack “some unique elements of expression.”

The plaintiffs insufficiently pled a breach of an implied-in-fact contract based on discussions between Daniels and Disney executives between 2005 and 2009, she declared.

The case is Daniels v. The Walt Disney Company, 18-55635.

Copyright 2020, Metropolitan News Company