Wednesday, January 30, 2019

Page 1

Court of Appeal:

Contract Action Against Ex-Fiancé Over Frozen Embryos Not a SLAPP

Opinion Says Actress Sofia Vergara Established Probability of Prevailing In Showing Breaches of Agreement; Malicious Prosecution Suit Barred

By a MetNews Staff Writer

|

|

|

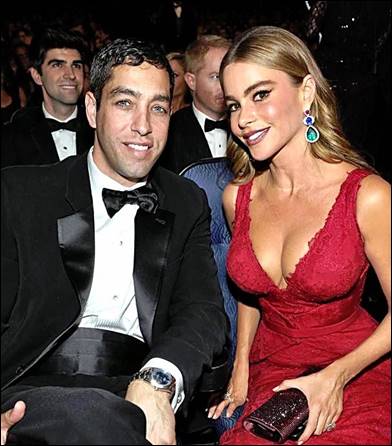

—AP Actors Sophia Vergara and Nick Loeb are seen in a photo taken prior to their 2014 break-up. The Court of Appeal on Monday held that Vergara’s Los Angeles Superior Court action may proceed in which she alleges Loeb’s breaches of an agreement relating to frozen embryos. |

The Court of Appeal for this district has declared that actress Sofia Vergara’s breach of contract lawsuit against her ex-fiancé arising from his attempts to gestate the pair’s frozen embryos is not a SLAPP.

However, Div. Five held that her claim of malicious prosecution must be stricken as she did not show a probability of its success on the merits.

Justice Carl H. Moor wrote for the majority and Justice Dorothy Kim partially dissented. The opinions were filed Monday and were not certified for publication.

The Feb. 14, 2017 suit by Vergara, star of the ABC television series “Modern Family,” was brought while two actions against her were pending, one in Los Angeles Superior Court and the other in Louisiana. Both actions were attempts by her former fiancé, actor/producer/director Nick Loeb, to take custody of the two cryogenically frozen embryos the couple had conceived in 2013 via in vitro fertilization during their engagement and to have them implanted in a surrogate mother.

The Beverly Hills clinic involved in the matter, ART Reproductive Center, is also a defendant in Vergara’s suit, but was not party to Loeb’s anti-SLAPP motion nor the appeal.

Loeb’s two actions were eventually dismissed—the 2014 Los Angeles Superior Court action on Loeb’s own motion and the 2016 Louisiana suit, brought by a trust created by Loeb for the benefit of his unborn daughters, after the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana (to which a state-court action had been removed) found it lacked personal jurisdiction over the actress.

Trial Court Proceedings

Denying Loeb’s special motion to strike, Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Raphael A. Ongkeko found that Loeb succeeded in showing that Vergara’s claims were based on his protected activity in maintaining litigation—satisfying the first prong of the anti-SLAPP statute—but that Vergara met the burden, which shifted to her, of demonstrating a probability of success on the merits.

In considering the causes of action founded on a contract—for declaratory relief and breach of oral contract—the judge examined the agreement entered into by the parties, which provides:

“One person cannot use the [c]ryopreserved [m]aterial to create a child (whether or not he or she intends to rear the child) without explicit written consent of the other person (either by notary or witnessed by [a clinic p]hysician staff member or [its] staff).”

Ongkeko also credited Vergara’s contention that the filing of the Los Angeles Superior Court case supported her claim of malicious prosecution.

Vergara based that claim on Loeb’s request before filing his suit that she consent to his custody of the embryos, evidencing his awareness that her consent was required under the contract; that he had obtained abortions for two of his prior girlfriends, reflecting the pretextual nature of his claimed pro-life rationale for his lawsuit; and his admission that he had not been forced to sign the agreement, notwithstanding his contention that he did so under duress.

Litigation Privilege

Loeb insisted that the contract causes of action against him were barred by the litigation privilege. Moor disagreed.

Focusing primarily on the action filed in Louisiana by the “Nick Loeb Louisiana Trust No. 1” for the benefit of Loeb’s “two daughters, Isabella Loeb and Emma Loeb,” who were “presently in a cryopreserved embryonic state,” the jurist said:

“In describing the conduct at issue, Loeb invites us to focus our attention on his own rights to access the courts and to obtain a judicial resolution of disputes about the meaning, scope, interpretation, or enforceability of the form directive. But Loeb engaged in conduct well beyond accessing the courts on his own behalf—without Vergara’s consent, he unilaterally caused the pre-embryos to file litigation as plaintiffs (and juridical people) in court in Louisiana, and he unilaterally chose for the pre-embryos the positions they would take, including: seeking to give Loeb control over them; preventing Vergara from invoking the form directive in deciding how the pre-embryos would be used; seeking a finding that Vergara tortiously interfered with the pre-embryos’ rights to be transferred to a surrogate; and terminating Vergara’s parental rights.”

Access to Courts

Moor went on to say:

“Vergara’s claims, to the extent they are based on Loeb creating the trust and causing the pre-embryos to file suit on their own behalf, in no way undermine Loeb’s own access to the courts to litigate his issues relating to the form directive. Indeed, Loeb’s filing of the Santa Monica lawsuit proves such access; despite free access to the California courts to resolve his own claims relating to the meaning, scope, and enforceability of the form directive, he elected voluntarily to dismiss his suit.

“Moreover, to the extent Loeb is contending that his access to the Louisiana courts needs to be protected by application of the litigation privilege here, we disagree. First, Loeb was not even a party to the Louisiana action: the pre-embryos and the trust filed suit. Second, access to the Louisiana courts is particularly insignificant, given that the federal court ruled Louisiana did not even have personal jurisdiction over Vergara.”

He also observed that the agreement signed by the parties was “reasonably susceptible to an interpretation prohibiting the unilateral use of the pre-embryos to create juridical persons and use them in an effort to avoid the form directive’s requirement of written consent.”

Moor said that Vergara failed to show a probability of prevailing in the action for malicious prosecution because she failed to demonstrate that Loeb had an awareness that his claims lacked merit. His seeking Vergara’s consent to his custody of the embryos, history of having funded abortions, and his admission that he was not forced to sign the agreement fell short of establishing such knowledge, he declared.

Kim agreed with the reversal of Ongkeko’s order granting the anti-SLAPP motion, but disagreed with the order that, on remand, he strike only the cause of action for malicious prosecution. She wrote:

“[I]n my view, Vergara’s breach of contract claims are barred, as a matter of law, by the litigation privilege. The allegations in Vergara’s complaint belie her argument on appeal that her claims are ‘based on breach of a separate promise independent of the litigation.’…Where, as here, a plaintiff alleges that a defendant undertook an action for the ‘sole purpose’ of filing litigation, the privilege should apply.”

Kim added:

“As the majority notes, Loeb was not a party to the Louisiana action but instead filed the action in the purported name of the pre-embryos and the trust. But an anti-SLAPP motion may be brought on behalf of another ‘person.’…I am not persuaded that the unique designation of the plaintiffs in the Louisiana action lessens the ‘principal purpose’ of the litigation privilege…Application of the litigation privilege here would promote this principal purpose, by enabling a litigant the utmost freedom of access to the courts to test the meaning, scope, interpretation, and enforceability of the form directive.”

The case is Vergara v. Loeb, B286252.

Jennifer J. McGrath of Theodora Oringher PC in Century City represented Loeb. Vergara’s counsel were Susan Allison of Jeffer, Mangels, Butler & Marmaro in Century City and Fred Silberberg of Beverly Hills.

Copyright 2019, Metropolitan News Company