Thursday, September 12, 2019

Page 1

C.A. Rejects ‘Free Demolition’ Theory by Derelict Tenant

Lessee That Allowed Property to Become ‘Home to Vandals, Vagrants and Transients,’ Resulting in Fires, Cannot Gain Slash in Damages on Notion That Land Was Worth More After Buildings Were Razed

By a MetNews Staff Writer

|

|

|

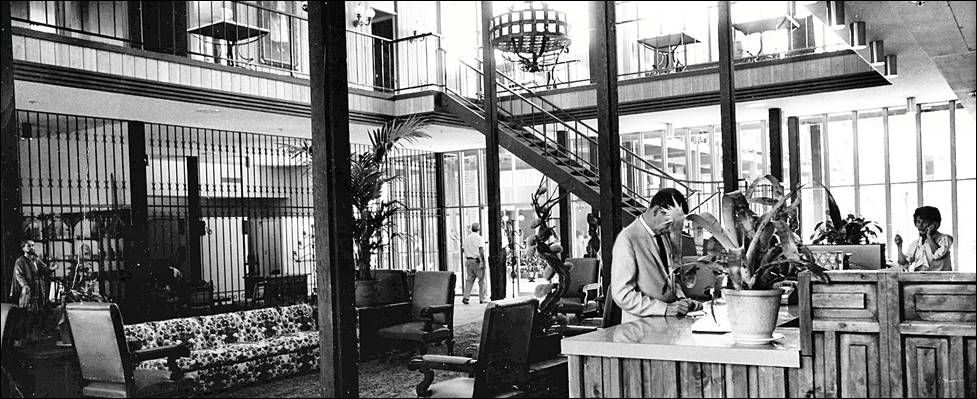

The Saddleback Inn, which was located in 1660 East First Street in Santa Ana, is seen in its heyday. The parcel on which it was situated is now an empty lot. |

Div. Three of the Fourth District Court of Appeal has rejected a theory that damages to the owners of the land on which the Saddleback Inn in Santa Ana had lain, burned down in two fires resulting from the tenant’s neglect, should be pared by $4.1 million because the lessee provided a free demolition, increasing the value of the parcel.

“Sometimes a defendant’s violation of some right of the plaintiff will have the serendipitous effect of actually conferring a benefit on the plaintiff which mitigates putative damages,” Justice William W. Bedsworth said in an unpublished opinion filed Tuesday. “This is known as the special benefit doctrine; its application reduces what the defendant owes to the plaintiff by the value of the special benefit.”

That doctrine, the jurist declared, does not apply to the present case. The opinion affirms a $5,945,943 judgment against the tenant, JK Properties, which in 2002 assumed an existing 55-year lease.

The owner of the inn, opened in 1964—once fashionable, and visited by Presidents Ronald Reagan and Richard Nixon—was the Elks Building Association of Santa Ana. The inn was on a 2.431-acre parcel; the adjacent parcel used by the Elks for their lodge was four acres

Fenced Property

As Bedsworth recounts the events in his opinion:

“For the first few years JK ‘poured in money’ for capital improvements. But by 2007, it had decided to put a fence around the property and let it lie fallow, even though it continued to make the lease payments. During this time the property became a home to vandals, vagrants and transients.

“Not surprisingly, in early 2011, there was a fire at the southernmost building on the property, severely damaging it.”

The city ordered JK to demolish the fire-struck building and all three of the other structures; it had only the fire-struck building demolished; the city obtained the appointment by an Orange Superior Court judge of a receiver; a second fire broke out in 2013, damaging the remaining structures, including the main building; the receiver had a demolition outfit remove the rubble.

“The once proud Saddleback Inn had been swept with the broom of destruction,” Bedsworth wrote.

The Elks put the property up for sale but the only buyer it could find conditioned the purchase on a sale of both parcels. The Elks agreed, garnering $18 million.

JK insisted a higher purchase price was obtained because it had provided a free demolition service. Bedsworth found the theory unavailing.

No Tort

The special benefit doctrine, he pointed out, requires a benefit arising from a tortious act, with that benefit mitigating the damages.

He continued:

“It is important in this case to note that JK really didn’t even perform the “free” service of demolishing the Elks’ property. Strictly speaking, JK neglected the property to the point it was occupied by transients and a fire occurred in one of the four buildings. The ensuing destruction of that building was so bad that JK had to comply with a City order to demolish what was left of that building. But the City also ordered JK to demolish the other three buildings and JK refused to comply. Those buildings were ultimately torn down not by JK, but by the receiver. So, to the degree that the San Diego developer did not have to factor in the cost of demolition when it bought the property in 2016, it was mostly no thanks to JK. The yeoman’s work of demolition was done by the receiver. And the only reason JK even bothered to demolish the first building was that a fire had already destroyed most of it.”

JK’s Calculations

Bedsworth also took issue with JK’s calculations in asserting that it bestowed a benefit. They were premised on the notion that the per-acre value of the lodge parcel and the inn parcel were identical.

The justice said:

“For all the record shows, the buyer might have paid a disproportionately large amount for the lodge parcel and a disproportionately small amount for the inn parcel. After all, he was unwilling to buy the inn parcel without the lodge parcel.

“Thus, to have shown JK’s breach somehow conferred the benefit of free demolition on the Elks, JK would have had to put on its own evidence in mitigation. At the least it would have had to establish (a) the fair market value of the inn parcel in 2016 with the original buildings as JK should have returned them to the Elks, and (b) the fair market value of the inn parcel in 2016 as a piece of vacant land. No such evidence was offered.”

Insurance Proceeds

JK also challenged the component of the judgment requiring it to pay $2.9 million to the Elks—the amount JK received from an insurance company based on the 2011 fire. Bedsworth declared:

“The fact JK received $2.9 million in insurance proceeds for the 2011 fire was substantial evidence that the Elks’ damages for JK’s failure to return at least the one building were at least $2.9 million.”

JK failed to produce countervailing evidence, he said.

The case is Elks Building Assn. of Santa Ana v. J.K. Properties, Inc., G056187.

Peter Abrahams and Scott P. Dixler of the Burbank appellate firm of Horvitz & Levy joined with Century City lawyer Parry G. Cameron in representing JK. Kevin A. Day and Jacob M. Clark of the Santa Ana office of AlvaradoSmith presented the Elks’ position.

Copyright 2019, Metropolitan News Company