Monday, January 28, 2019

Page 1

Court of Appeal:

Label Saying That Olives Are ‘Pitted’ Doesn’t Authorize Action Based on Injury From Pit

Opinion Points to Small-Print Warning on Back Label to Beware of Pits

By a MetNews Staff Writer

|

|

|

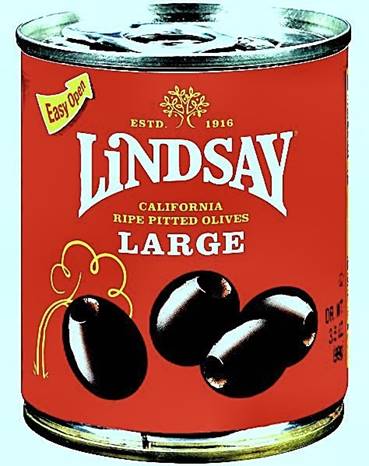

Pictured above is a can of “Lindsay California Ripe Pitted Olives.” The representation on the label that the olives are pitted does not give rise to a cause of action based on strict products liability or breach of warranty, the Court of Appeal held Thursday, because pits are naturally present in olives and an advisory appears on the back label to watch out for pits. |

The 82-year-old rule that there’s no product liability for injuries from substances that naturally occur in a food cannot be avoided by a plaintiff, who cracked a tooth on a pit in an olive, by pointing to the words on the label of the jar reading, “PITTED OLIVES,”the First District Court of Appeal has held.

Justice Alison M. Tucher of Div. Four wrote the unpublished opinion, filed Thursday, which affirms a summary judgment in favor of defendant Bell-Carter Foods, producer of Lindsay-brand canned olives. The opinion points to an admonition on the back label to watch out for pits.

The plaintiff, Susan Steele, incurred her injury after biting into one of that brand’s large “pitted” olives.

Summary judgment was granted by Contra Costa Superior Court Judge Judith S. Craddick who held that Steele’s action, based on strict products liability and breach of warranty, was foreclosed by the California Supreme Court’s 1992 decision in Mexicali Rose v. Superior Court. There, the high court, reaffirmed its holding, with respect to those theories, set forth in the 1936 case of Mix v. Ingersoll Candy Co.

Chicken-Bone Cases

In Mix, it held that a restaurant owner could not be liable to a customer who was injured by a chicken bone contained in a chicken pot pie, declaring:

“Bones which are natural to the type of meat served cannot legitimately be called a foreign substance, and a consumer who eats meat dishes ought to anticipate and be on his guard against the presence of such bones.”

The court in Mexicali Rose dealt with a patron who was injured from injesting a chicken bone in an enchilada. The rule announced in Mix against causes of action based on strict liability and breach of an implied warranty based on harm from a natural substance in a dish was retained, though the court did announce the availability of a cause of action for negligence where “the presence of the natural substance is due to a restaurateur’s failure to exercise due care in food preparation.”

Steele sought to distinguish precedent on the basis of the representation on the Lindsay labels that the olives are pitted.

Strict Liability

Although the words “Caution: Look out for Pits!” do appear in small print on the backs of Lindsay labels, the plaintiff argued, this does not preclude an action based on strict liability, but merely creates a triable issue of fact as to whether the warning was adequate. Tucher responded:

“Steele’s strict liability failure to warn theory is inconsistent with the governing principles outlined in Mexicali Rose, which preclude her from relying on any strict liability theory to recover damages for an injury caused by a natural substance in a food product. Steele cannot avoid this controlling precedent by mischaracterizing her failure to warn theory as a distinct ground for imposing liability on Bell-Carter.”

The fact that Bell-Carter, unlike the defendant in Mexicali Rose (and Mix) was not a restuarant does not matter, Tucher said, because the principle was subsequently extended to retailers of food products.

While the plaintiffs in Mix and Mexicali Rose dealt with the implied warranty of merchantability and fitness of something sold, Steele alleged a breach of an express warranty: that the olives were pitted. She relied on an express warranty case—Lane v. C. A. Swanson & Sons, handed down by the Court of Appeal for this district in 1955—which reversed a judgment in favor of the maker of Swanson’s canned “boned chicken.”

The opinion in that case says that the label, proclaiming the content to be “boneless,” when “coupled with the representation in the newspaper ads that the contents contained no bones, constituted an express warranty” and that the warranty was breached in the case of the plaintiff. He swallowed a bone that was present in the product and it became lodged in his throat.

Steele argued that the phrase “pitted olives” on the Lindsay label “is the equivalent of the phrase ‘boned chicken’ ” in the action against Sawnson.

“In isolation, perhaps,” Tucher responded. “But that is where the analogy ends.”

She explained:

“The evidence in Lane showed that the label on the can of boned chicken went beyond mere identification and constituted an affirmative promise—at least when considered in conjunction with defendants’ advertising—that there were no bones in the chicken. Here, by contrast, the olive can label contained a statement cautioning consumers that the olives could contain pits. Furthermore, Steele did not produce any type of advertisement that could be construed as a promise or warranty that there were no pits or pit fragments in the olives.”

The case is Steele v. Bell-Carter Foods, Inc., A151952.

|

|

|

|

The label on the back of the olive cans includes the words, “CAUTION: LOOK OUT FOR PITS!” The Court of Appeal opinion holds that there is no triable issue of fact as to whether those words constitute a warning sufficient to overcome an action.based on strict product liability.brought by a person injured by biting into an olive from one of those cans. |

|

Copyright 2019, Metropolitan News Company