Thursday, August 29, 2019

Page 7

SPECIAL FEATURE:

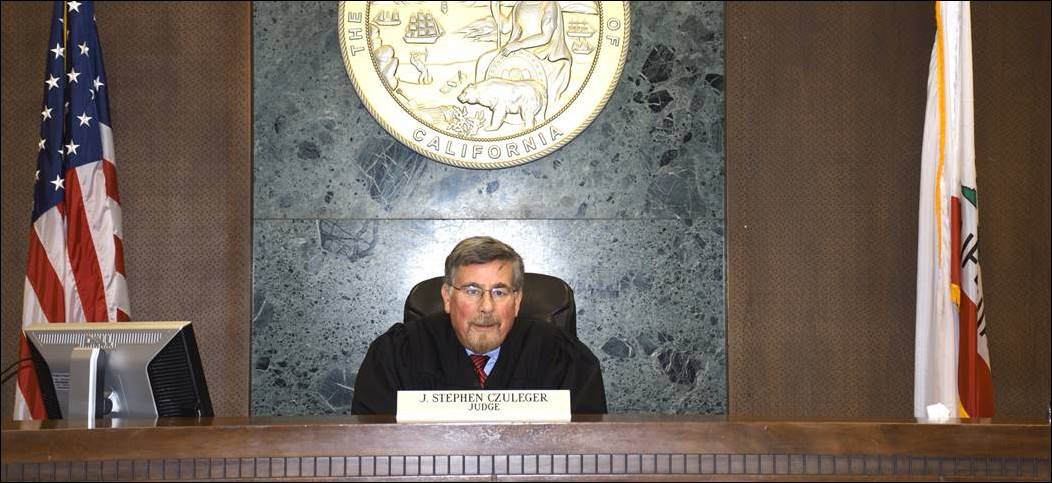

Returning to Courtroom 16 at the Spring Street Courthouse

By J. STEPHEN CZULEGER

|

|

(The writer is a judge of the Los Angeles Superior Court and is a former presiding judge. In the following article—which originally appeared in Gavel to Gavel, a magazine for the court’s bench officers—he tells of moving to the former U.S. District Court courthouse, now a Superior Court facility, and sitting in the courtroom where, as a law clerk, he began his career in the legal profession.)

|

I |

N THE FALL OF 1974, I came to the federal courthouse at 312 North Spring Street for the first time. In Courtroom 16—now Department 16—I interviewed for a position as law clerk/crier with U.S. District Judge David W. Williams. I was hired shortly thereafter and started my first legal job in October 1974. So began my career in the law.

Now, after 30 years on the bench, I have returned to that same courtroom and I sit in the same chambers that I interviewed in nearly 45 years ago. I had no idea in 1974 that this courtroom—which remains virtually unchanged after four decades—would become such an important part of my life and would later become my courtroom. I also was not initially aware that Judge Williams was a legend.

|

|

|

David Welford Williams, who was born March 20, 1910 and died May 6, 2000, was a judge of the United States District Court for the Central District of California. Los Angeles Superior Court Judge J. Stephen Czuleger, who served as a law clerk for him, remembers the judge with fondness and admiration. |

Judge Williams was the first African-American federal judge west of the Mississippi. In 1956, he was one of the first African-American judges appointed to the bench in California. Prior to that, he practiced law and worked with Thurgood Marshall to overturn restrictive racial covenants in California. He was appointed to the federal bench in 1969, after 14 years on the state bench. Today his name appears on the wall of the Clara Shortridge Foltz Criminal Courts Building on the Hall of Fame List.

Judge Williams was the first judge to occupy Courtroom 16. I was privileged to join him there five years after he first moved to Spring Street.

MY TWO YEARS WORKING for this exceptional jurist were some of the most enjoyable of my career. He was my mentor, and my choice to go on the bench was driven in large part by his example and encouragement. Today, there are a score of prominent lawyers who can say they have a Judge Williams pedigree.

There are too many to name here. I don’t want to run the risk of leaving someone off the list, so I won’t attempt to acknowledge them all. However, two of my colleagues on the Superior Court, Judges Tim Saito and Tony Richardson, also had the opportunity of working with Judge Williams in Courtroom 16. U.S. District Judge Percy Anderson is also an alumnus. I am sure they all share my respect for Judge Williams and have valued to this day their time in Courtroom 16.

To say it was unnerving for me to take the bench for the first time in Courtroom 16 would be an understatement. For more than two years, when not doing research and writing, my job was to call Judge Williams’ court to order. I sat at the small table to the right of his bench and watched a judicial master at work. He was always thorough, thoughtful and understanding.

Those who appeared before him often thought him to be severe. However, as I look at the bench now, I recall a man with a great sense of humor. Often I would hear a slap on the bench indicating a note from the judge. Those notes were inevitably a joke and it was often difficult to keep a straight face in court. Except for an occasional, barely perceptible smirk, the judge’s demeanor did not change while he attempted to entertain me during a boring trial.

A summons to chambers from the law clerk’s office could either be for a new assignment or to sit and listen to Judge Williams talk about growing up black in Los Angeles. No matter what I was called for, I never failed to learn from him.

My law clerk’s office is now the library for the building. My chambers connects to it. I walk in some days now and look around in amazement. While only a few feet from chambers, it is a lifetime away. At least now, I do not have to keep the library up to date.

A RECENT ARTICLE ABOUT our court’s move to the Spring Street location mentioned that one of the chambers had a fireplace. That would be Courtroom 16. The suggestion of the article was that it was rich and ornate. It is not. Very few know the history of that fireplace. I do.

Judge Williams was the last of the federal judges to move into what was one of the newly built courtrooms on the Spring Street level. Before the 1960s, when those courtrooms were built out, the Spring Street floor was the main U.S. Post Office in Los Angeles.

With the growth in Southern California, the original facilities built in 1939, were insufficient and another floor of courtrooms for the federal courts was necessary. With the lowest seniority in 1969, Judge Williams got what was not the most desirable of the newly built out Spring Street courtrooms. The windows in chambers overlooked Main Street. One window on the north of chambers however, overlooked the upper parking lot and the trash cans for the building.

Judge Williams did not care for the view and the racket. Somehow he got the General Services Administration to panel over the window and install a faux fireplace—all in laminate wood paneling. That is how the fireplace came into being.

When I moved here in April of this year, I showed staff where the secret door was located, reached in and flipped the hidden switch. Fifty years later, the fake logs lit up and the straining electric motor made its sick crackling sound. This is not as luxurious as one might have imagined about a chambers’ fireplace, but it still works almost 50 years after Judge Williams had it installed.

|

|

|

David Welford Williams, who was born March 20, 1910 and died May 6, 2000, was a judge of the United States District Court for the Central District of California. Los Angeles Superior Court Judge J. Stephen Czuleger, who served as a law clerk for him, remembers the judge with fondness and admiration. |

The law clerks back then had fun showing externs the crackling fireplace and waiting to see how long it took them to figure out it was not real. We would go into the judge’s chambers while he was out and make a production of rubbing our hands together and saying how nice and warm it was. To this day, those who worked in Courtroom 16 tell fireplace stories.

JUDGE WILLIAMS PASSED AWAY in 2000 at the age of 90. Fortunately, he was alive for many years after I was appointed to the bench in 1988. One day, he asked me to lunch and, as he dropped me back at the courthouse, he said, “Steve, if you don’t make me call you judge, you can call me by my first name now.” I thanked him but replied, “Judge, I’ve been calling you ‘Judge’ for so long, I thought that was your first name.”

Judge Williams swore me into the Superior Court. That was a joy.

During his tenure on our court, he was the supervising judge of the Criminal Courts and also of the West District. I think one day he would have been the first black presiding judge of the Superior Court had he not been appointed to the federal bench.

I only wish he had been alive when I became the presiding judge. I think that would have pleased him greatly. I hope he would be pleased that I inherited his old courtroom years later. Coming back here fills me with both pride and melancholy. The spirit of Judge Williams still lives here.

By the way, Judge Williams’ family gave me his robes after he passed. They have been returned to his chambers and now hang again in the closet of Courtroom 16 and no, I never wear them.

Copyright 2019, Metropolitan News Company