Tuesday, July 31, 2018

Page 1

Ninth Circuit:

Norton Simon Museum Can Keep Nazi-Confiscated Paintings

By SHANE PATRICK ETCHISON, Staff Writer

The Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals yesterday affirmed the award of summary judgment to the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena, holding that a wealthy European heiress cannot recover the Nazi-confiscated paintings because the Dutch government’s sale of the paintings in 1966 was an “act of state” and must be deferred to.

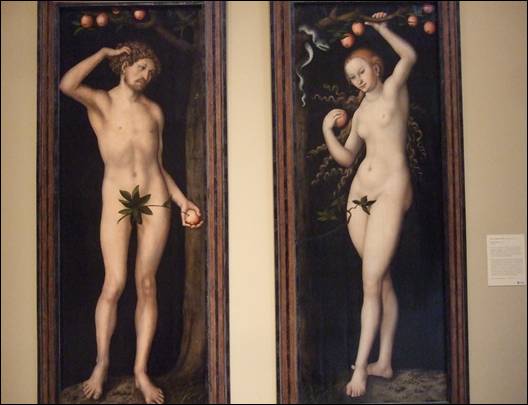

The two panels, depicting Adam and Eve, were painted by Lucas Cranach the Elder around 1530 and are currently on view at the museum. Marei von Saher, heiress of the family from whom the Nazis confiscated the paintings, sued the museum in U.S. District Court for Central District of California in 2007, seeking the return of the paintings.

The litigation between von Saher and the museum resulted in three Ninth Circuit opinions, the latest of which was written by Circuit Judge M. Margaret McKeown and affirms the granting of the museum’s motion for summary judgment, applying the federal “act of state” doctrine.

McKeown explained:

“Our judiciary created the act of state doctrine for cases like this one. In applying it, we presume the validity of the Dutch government’s sensitive policy judgments and avoid embroiling our domestic courts in re-litigating long-resolved matters entangled with foreign affairs….For all the reasons the doctrine exists, we decline the invitation to invalidate the official actions of the Netherlands.”

|

|

|

—AP This composite image shows panels of Adam and Eve painted c. 1530. (Norton Simon Art Foundation) |

Old Dispute

The opinion begins by noting that, while the paintings have been in Pasadena for nearly 50 years, the ownership dispute over them goes back to the Nazi invasion of the Netherlands during World War II.

In 1931, von Saher’s father-in-law, Jacques Goudstikker, bought several paintings, including the Cranachs, from the Soviet Union as part of what was billed at auction as the Stroganoff Collection. McKeown noted that District Judge John F. Walter found that the Stroganoffs, a Russian noble family, had not actually owned the collection, but did not reach a determination of that matter in her opinion.

Goudstikker fled his native Netherlands ahead of the Nazi invasion. Hermann Göring, one of Nazi Germany’s top commanders and a notorious confiscator of Jewish-owned art, purchased Goudstikker’s firm in an involuntary sale and took possession of its assets, including the paintings.

After the allied forces won the war, the Cranach works were turned over to the Dutch government, which implemented a process for people to reclaim such stolen works.

Attempted Recovery

Pursuant to that process, Goudstikker’s widow attempted to recover the Cranach paintings, but ultimately released her claim to them. Subsequent attempts by von Saher to renew the claim were not availing.

George Stroganoff-Sherbatoff (the opinion refers to him simply as “Stroganoff”), who was born a Russian prince but later renounced his title in order to become an American citizen and serve in the U.S. Navy in World War II, had an ongoing dispute with the Dutch government, claiming that as a member of the Stroganoff family the Cranach paintings were rightfully his. The Dutch government settled the dispute with the former prince by allowing him to purchase the paintings in 1966, after they had determined von Saher had no right to them.

Stroganoff-Sherbatoff sold the Cranach paintings to the museum for $800,000 in 1971.

First Appeal

The first appeal in the litigation between the heiress and the museum came after the District Court ruled unconstitutional the California law under which von Saher initially sued. That law had extended the statute of limitations for claims against museums for Holocaust-era artwork through the end of 2010.

The Ninth Circuit affirmed the district court’s dismissal, finding that field preemption invalidated the California Legislature’s attempt to engage in foreign affairs. The court did allow von Saher leave to amend her complaint if she could allege facts bringing the claim under a generic state statute of limitations.

Shortly after that opinion was filed, California extended the statute of limitations for recovery claims against museums for stolen artwork to six years after actual discovery by the claimant. Von Saher amended her complaint, but in 2014 the District Court once against dismissed it, this time finding that the claims conflicted with foreign policy.

Second Appeal

A panel of the Ninth Circuit reversed the district ruling, noting that, according to the amended complaint, the paintings had not been subject to the Netherlands’ internal restitution process and that the dispute in the case was simply one between private parties.

Circuit Judge Kim McLane Wardlaw dissented to that opinion. In her view, an amicus brief filed by the U.S. government clearly explained that the foreign policy of the federal government held that “World War II property claims may not be litigated in U.S. courts if the property was ‘subject’ or ‘potentially subject’ to an adequate internal restitution process in its country of origin.”

Wardlaw’s reading of the federal foreign policy led her to conclude that the claim was preempted. In that dissent, McKeown notes, Wardlaw mentioned but did not reach the question of whether the Dutch sale to Stroganoff-Sherbatoff was an act of state which would be afforded deference.

Act of State

The latest appeal came after Walter granted the museum summary judgment, applying an analysis of Dutch law. The panel agreed with the ruling, but indicated that the analysis had gone too far.

McKeown explained:

“We view the conveyance not as a one-off commercial sale, but as the product of the Dutch government’s sovereign internal restitution process. Under that process, the Netherlands passed Royal Decrees E133, to expropriate enemy property, and E100, to administer a system through which Dutch nationals filed claims to restore title to lost or looted artworks. Whatever the exact legal effect of those decrees—and irrespective of whether the district court correctly interpreted their meaning under Dutch law—we cannot avoid the conclusion that the post-war Dutch system adjudicated property rights by expropriating certain items from the Nazis and restoring rights to dispossessed Dutch citizens.”

She continued:

“Expropriation of private property is a uniquely sovereign act.”

The jurist further explained that the sale of the artworks to Stroganoff-Sherbatoff after von Saher’s failed attempt to claim them, and a 1999 Dutch appellate court decision holding that the process which the Netherlands had implemented was valid under international law both supported the conclusion that the sale was an act of state.

No Applicable Exception

The opinion rejects von Saher’s contentions that an exception to the act of state doctrine should apply to her claim.

McKeown acknowledged that purely commercial acts are exempt from the deference afforded by the doctrine. But expropriation and government restitution, she noted, are acts unique to sovereignties and are never purely commercial.

She also declined to apply the so-called “Second Hickenloper Amendment” which restricts the act of state doctrine for takings occurring during or after 1959. She noted that the Dutch government did not take anything after that date, but had already been notified of the Goudstikker family’s waiver of their right to restore possession by the time they sold the paintings.

Wardlaw’s Concurrence

Wardlaw concurred with the opinion, but attached her dissent from the earlier appeal to her brief concurrence. She noted:

“This case should not have been litigated through the summary judgment stage. The district court correctly dismissed this case on preemption grounds in March 2012. Those grounds did not require any further factual development of the record, and were valid even taking all of the facts in the light most favorable to Von Saher. So here we are in 2018, over a decade from the date Von Saher filed her federal action, reaching an issue we need not have reached, to finally decide that the Cranachs, which have hung in the Norton Simon Museum nearly fifty years, may remain there.”

The case is Von Saher v. Norton Simon Museum of Art, no. 16-56308.

Fred A. Rowley Jr. of Munger Tolles & Olsen’s Los Angeles office argued on appeal for the museum. Von Saher was represented before the panel by Lawrence M. Kaye of Herrick Feinstein LLP in New York.

Copyright 2018, Metropolitan News Company