Wednesday, September 20, 2017

Page 1

Ninth Circuit Blocks Ordinance Requiring Warning in Soda Ads

Questions the Accuracy of the Prescribed Message and Says the San Francisco Proviso Would ‘Chill’ Commercial Speech; Warning Would Comprise 20 Percent of Ad

By a MetNews Staff Writer

|

|

|

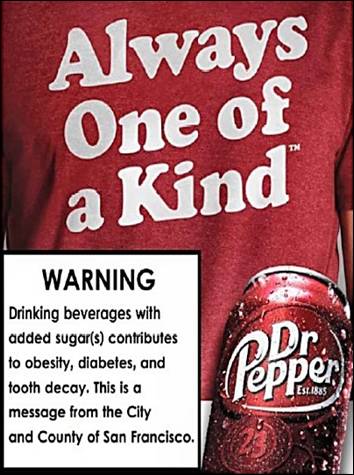

—AP Above is a sample soda ad, attached to yesterday’s Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals’ opinion blocking a San Francisco ordinance that would require a health warning on ads for sugary drinks. The court held that the warning violates freedom of speech and its accuracy is doubtful. The court noted that the wording comprises 20 percent of the ad. |

The Ninth U.S. Court of Appeals yesterday ordered that a San Francisco ordinance be blocked from going into effect, holding that a prescribed health warning on soda ads would suppress commercial speech and is of doubtful accuracy.

The opinion, by Circuit Judge Sandra Ikuta, reverses a decision by District Court Judge Edward M. Chen of the Northern District of California denying a preliminary injunction to the plaintiffs, the American Beverage Association, the California Retailers Association, and the California State Outdoor Advertising Association.

Ikuta wrote:

“Because the ordinance is not purely factual and uncontroversial and is unduly burdensome, it offends the Associations’ First Amendment rights by chilling protected commercial speech.”

She noted:

“Indeed, the Associations submitted unrefuted declarations from major companies manufacturing sugar-sweetened beverages stating that they will remove advertising from covered media if San Francisco’s ordinance goes into effect. This evidence supports the Associations’ position that the disclosure requirement is unduly burdensome because it effectively rules out advertising in a particular medium….”

The three-judge panel stopped the 2015 ordinance from going into effect, pending resolution of the litigation.

Prescribed Wording

The ordinance requires a warning on ads—comprising 20 percent of the space—saying:

“WARNING: Drinking beverages with added sugar(s) contributes to obesity, diabetes and tooth decay.”

Ikuta noted that the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1985 decision in Zauderer v. Office of Disciplinary Counsel of Supreme Court of Ohio upheld a State Bar requirement “that any advertisement that mentions contingent-fee rates must...inform clients that they would be liable for costs (as opposed to legal fees) even if their claims were unsuccessful” because the advisement was “purely factual and uncontroversial.”

That, Ikuta said, cannot be said of the message required by the City and County of San Francisco.

‘Controversial,’ at Least

She declared:

“We conclude that the factual accuracy of the warning is, at a minimum, controversial as that term is used in the Zauderer framework. The warning provides the unqualified statement that ‘[d]rinking beverages with added sugar(s) contributes to obesity, diabetes, and tooth decay,’…and therefore conveys the message that sugar-sweetened beverages contribute to these health conditions regardless of the quantity consumed or other lifestyle choices. This is contrary to statements by the FDA that added sugars are ‘generally recognized as safe,’…and ‘can be a part of a healthy dietary pattern when not consumed in excess amounts’….Because San Francisco’s warning does not state that overconsumption of sugar-sweetened beverages contributes to obesity, diabetes, and tooth decay, or that consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages may contribute to obesity, diabetes, and tooth decay, the accuracy of the warning is in reasonable dispute.”

Ikuta added that the warning is “misleading and, in that sense, untrue” because it creates the erroneous impression that sugar-sweetened beverages are more unhealthful than other products, not carrying warnings, with equal or more calories.

She pointed to an FDA pronouncement that “added sugars, including sugar-sweetened beverages, are no more likely to cause weight gain in adults than any other source of energy.”

Undue Prominence

Also of concern was the required prominence of the warning. The ordinance requires that the warning “be enclosed in a rectangular border” that it “shall occupy at least 20% of the area” the ad.

“[T]the black box warning overwhelms other visual elements in the advertisement,” Ikuta said. “As such, it is analogous to other requirements that courts have struck down as imposing an undue burden on commercial speech, such as laws requiring advertisers to provide a detailed disclosure in every advertisement,…to use a font size ‘that is so large that an advertisement can no longer convey its message,’…or to devote one-sixth of the broadcast time of a television advertisement to the government’s message….”

Concurring in the judgment, Judge Dorothy Nelson centered on the size of the warning. She said:

“I concur in the judgment of this case because I believe that the ordinance, in its current form, likely violates the First Amendment by mandating a warning requirement so large that it will probably chill protected commercial speech….While I do not understand the majority’s opinion to state that no properly worded warning would pass constitutional muster, I agree that the City has not carried its burden in demonstrating that the twenty percent requirement at issue here would not deter certain entities from advertising in their medium of choice. Because this case can be disposed of on this question alone, I would reverse and remand without making the tenuous conclusion that the warning’s language is controversial and misleading.”

The case is American Beverage Association v. City and County of San Francisco, No. 16-16073.

Copyright 2017, Metropolitan News Company