Tuesday, August 8, 2017

Page 1

Ninth Circuit Affirms $42 Million Judgment Against Safeway

Panel Finds Grocery Company Promised Not to Charge Customers Ordering Online Higher Prices Than in Its Stores, but Did

By a MetNews Staff Writer

|

|

|

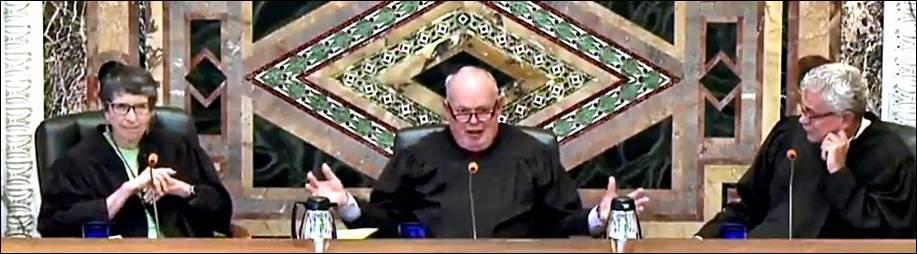

During oral argument in San Francisco on June 12, Ninth U.S. Circuit Judge N. Randy Smith of Idaho tells Safway’s lawyer that his client’s only hope is to be able to point to extrinsic evidence, saying that in “this phony district called California” such evidence is admitted liberally. He is flanked by Ninth Circuit Judge Mary Schroeder and U.S. District Judge Lawrence L. Piersol of the District of South Dakota, sitting by designation. |

The Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals has affirmed a judgment of nearly $42 million against Safeway, Inc., in a class action based on the nationwide grocery company’s charging of higher prices for home delivered goods ordered over the Internet than customers in their physical stores, in violation of a term of the online user agreement which, the court held, promised price parity.

Safeway—which has more than 1,300 stores nationally, and operates in Southern California and Nevada as “Vons,” with 273 outlets—required users of its home delivery services to register online, and agree to “Special Terms.” The term at the center of the controversy is this:

“The prices quoted on our web site at the time of your order are estimated prices only. You will be charged the prices quoted for Products you have selected for purchase at the time your order is processed at checkout. The actual order value cannot be determined until the day of delivery because the prices quoted on the web site are likely to vary either above or below the prices in the store on the date your order is filled and delivered.”

Safeway and the plaintiffs’ class representative, Michael Rodman, had differing interpretations of that language, with Rodman insisting that it constituted a promise not to charge online customers prices in excess of what was assessed in the company’s grocery stores, except for there being a modest delivery charge, which was otherwise delinerated. The U.S. District Court agreed with Rodman, and the Ninth Circuit affirmed Friday.

Despite close questioning of counsel during oral argument at a June 12 session of the court, convened in San Francisco, and seemingly keen interest in the case on the part of the judges, they affirmed in a pithy memorandum opinion that recited the trial court’s conclusions and indicated agreement.

Promises at Outset

Safeway did publicize in 2001, when it launched its online service, that, aside from the delivery fee, customers who electronically placed orders would not be charged more than in-store shoppers. However, on April 12, 2010, it began marking up prices of delivered goods.

As explained in a declaration submitted in the case:

“If the price of an item is between $0.00 and $0.99, the markup adds $0.10, from a $1.00 to $1.99, the markup adds $0.20 cents, from $2.00 to $2.99 the markup adds $0.30 cents, and so on.”

This change was not directly communicated to existing online subscribers to the delivery service, but was reflected in the user online agreement. Safeway relied upon a proviso in agreement that it could change the terms at any time, placing the burden on the user to periodically review the terms as posted on its website.

On Nov. 15, 2011—15 days after the District Court denied Safeway’s motion to dismiss Rodman’s action—Safeway added these words to its online agreement:

“Please note before shopping online” at Safeway.com “that online and physical store prices, promotions, and offers may differ.”

Those constituting the class are “[a]ll persons in the United States who: (1) registered to purchase groceries through Safeway.com at any time prior to November 15, 2011, and (2) purchased groceries at any time through Safeway.com that were subject to the price markup implemented on or about April 12, 2010.”

Summary Judgment Granted

On Dec. 10, 2014, U.S. District Judge Jon S. Tigar of the Northern District of California granted judgment in favor of the class. He later awarded the class $31 million in damages and $10.9 million in interest, and yet later imposed $516,000 in discovery sanctions.

While Rodman brought several causes of action, the class was certified solely in connection with a cause of action for breach off contract, decided under California law.

Tigar said, with respect to the three-sentence clause in issue:

“Plaintiff interprets this section to promise that, except for otherwise disclosed delivery fees, the customer will be charged the prices charged in the physical store where the groceries are selected, and that the prices quoted on the website are attempts to estimate those in-store prices. Defendant, on the other hand, argues that the phrase ‘the prices in the store’ means the prices in the online store, and that the terms explain to a customer that it if she places an order Monday for delivery Thursday, she will be charged the price that the online store displays for the product on Thursday.”

Tigar said that both parties were insisting that the language could be interpreted only one way, but that the resolution was not clear cut, so that he would look to extrinsic evidence. However, leaning toward Rodman’s interpretation, he found Safeway’s intrinsic evidence unpersuasive, and declared he needn’t bother to look at that put forth by the plaintiffs, such as surveys showing how the words of the agreement would commonly be interpreted.

Interpretation Rejected

He rejected Safeway’s insistence that the phrase “the prices quoted on the web site are likely to vary either above or below the prices in the store on the date your order is filled and delivered” referred to the online “store,” rather than the particular physical store from which the goods were to be gathered. Tigar said:

“It might be another matter if some other portion of the contract used the word ‘store’ by itself to refer to the safeway.com website. But in every other use of the term ‘store’ in the Special Terms, the word ‘store’ means a physical store….

“Plaintiffs’ interpretation of the contract gives effect to every one of three sentences in the first paragraph of the ‘Product Pricing and Service Charges’ section, is consistent with a reasonable objective reading of the language in light of the contract as a whole, and is a very compelling interpretation of the contract.”

The judge drew this conclusion:

“The Special Terms promise that, with the exception of the actually disclosed special charges and delivery fees, the prices charged for safeway.com products will be those charged in the physical store where the groceries are delivered. Since Safeway actually marked up the charges for the in-store prices beyond the disclosed delivery and special charges, the Court grants summary judgment that Safeway breached its contract with its customers.”

Effect of Change

Tigar said that those who signed up for the online services before the advisement that online prices do not track store prices was added to the agreement on Nov. 15, 2011 had no notice of the upcharging, and did not agree to it—and that assent “cannot be inferred from Class Members’ continued use of safeway.com” after that date, based on lack of notice.

“Instead,” Tigar wrote, “Class Members safeway.com use continued to be governed by the Special Terms that were operative at the time of their registration, which promised price parity.”

Safeway argued that even if damages weren’t cut off as of Nov. 15, 2011, they had to be precluded after Aug. 29, 2012, when it sent all users an email saying that online prices “may differ from your local store.”

Tigar responded:

“The Court does not agree that this email gave Class Members notice of the change to the Special Terms, as it did not refer to the Special Terms or indicate that Safeway had made any change to them. Moreover, Safeway admits the email was not sent to all Class Members, but instead was only sent to those users who had opened a safeway.com email within the last six months. Finally, the representation contained within the email, which stated that prices “may differ from your local store,” was not even factually accurate, as Safeway in fact always added a markup to items sold in the online store as compared to items sold in the physical store.”

Oral Argument

At oral argument, the judges sent a clear signal there would be an affirmance. Judge N. Randy Smith, whose chambers are in Pocatello, Idaho, told Safeway’s attorney, Brian Sutherland of Reed Smith, LLP:

“Supposin’ I tell you that if I had this in Idaho, and I were doing it under Idaho law, without looking at all this extrinsic evidence, you would lose on summary judgment. There’s nothing you can say that says to me that it’s opposite of what the district court did.

“The only reason you got any chance is ’cause you’re in this phony district called California that has all this extrinsic evidence that now I’ve got to look at. So what extrinsic evidence do I look at that confirms what you’re telling me?

“Because the judge looked at all the extrinsic evidence you gave and, looking at that extrinsic evidence, said ‘My interpretatiion is exactly what this extrinsic evidence is.’ ”

Sutherland responded that under the “Frequently Asked Questions” on the website is the query: “Will I pay the same prices online as in your stores?’ ” He said the answer is: “You will receive the prices and promotions that are applicable to your online store on the day of delivery.”

That, the lawyer said, alerts the consumer that “the prices are coming from the online store.”

There is also the matter of the “course of conduct,” he added. After April of 2010, he said, customers were bound to realize from the prices that “they’re getting the online mark-up,” and maifested assent from continuing to place online orders.

“Their course of performance confirmed their understanding of the contract,” he maintained.

‘In the Store’

Piersol’s questioning centered on the last sentence of the provision in question: “The actual order value cannot be determined until the day of delivery because the prices quoted on the web site are likely to vary either above or below the prices in the store on the date your order is filled and delivered.”

He said:

“ ‘[T]he prices quoted in the store. In the store. That’s hard to get around.”

Sutherland responded:

“That sentence is an accurate description. It’s an explanation. You can read that third sentence and not see any promise it.”

Piersol said: “Really?”

The lawyer persisted:

“No promise in it. No.”

Advertising Not Contractual

Smith quizzed the lawyer on the significance of advertising by Safeway between 2001 and 2009 that its online prices paralleled those in stores. Sutherland responded that “advertising is different from a contract.”

He said that while Safeway might make a same-prices promise in an ad, “it would never do it in a contract.”

An online shopper, Sutherland told the judges, is different from an in-store shopper and has different expectations. He said:

“Why ould you ever expect to get in-store prices, unless you were specifiocallt told thatm either in advertising or in the product pricing clause?”

Steven A. Schwartz of Chimicles & Tikellis LLP argued for the class, receiving only softball questions.

Tigar Affirmed

Friday’s memorandum opinion says, with respect to the interpretation of the agreement:

“We agree with the district court that both interpretations are reasonably susceptible readings of the Special Terms. We also agree with the district court that the extrinsic evidence supports Rodman’s reading.”

It also declares that Tigart was correct that Safeway could not modify the agreement without notice.

The memorandum says Safeway’s purported “voluntary payment” defense was without merit, explaining:

“It is questionable whether such a defense is available in an action for breach of contract, rather than restitution. Safeway provides no authority that California has extended the defense from restitution to legal claims, but even assuming it is, the defense fails in this case. The defense requires full disclosure and the undisputed evidence shows that Safeway did not make a full disclosure.”

The judges found class certification appropriate, noting:

“The legal issues pertain to all class members. None of the offered extrinsic evidence in this case went to individual conversations and representations made to individual class members, but instead went solely to class wide advertising and publicity by Safeway.”

The case is Rodman v. Safeway, Inc., No. 15-17390.

Copyright 2017, Metropolitan News Company