Thursday, January 14, 2016

Page 6

PERSONALITY PROFILE:

DEANELL REECE TACHA

From Kansas to Malibu, Federal Judge-Turned-Law School Dean Has ‘Done It All’

By KENNETH OFGANG, Staff Writer

|

I |

t’s 1,241.8 miles from Goodland, Kansas to Malibu.

But distance alone hardly describes the route Deanell Reece Tacha has taken. The prairie native—she still has a home in Kansas—has probably had as varied a career as any lawyer in America.

Can you name anyone else who has been a small-town sole practitioner, an associate at one of the country’s largest firms, a law professor and dean, and a federal appellate judge in between those two?

Not to mention being a 2015 MetNews Person of the Year.

It’s a story of determination, drive, and good timing. And like many such stories, it begins in a small town in the American Midwest.

Deanell Reece was born just after World War II in Goodland, just east of the Colorado state line. It is the town where her maternal grandparents lived, and where her mother lived while her father was in military service.

She actually grew up in Scandia, a town of 300 in North Central Kansas, where her late father, Harry William “Bill” Reece, ran a construction company building bridges and culverts and where her 95-year-old mother still lives. Reece Construction Co. was one of the first contractors to work on the Interstate highway system.

Her small-town educational experience was “fabulous,” she says. Teachers tended to remain at the local school for many years, and she soon regularly participated in events like the school spelling bee, which helped her develop skills she uses to this day.

“I’m my own spellcheck,” she explains.

Ponders Post-Graduate Studies

She went to the University of Kansas in Lawrence, the city she still calls home. Coming from a “very traditional” family, she thought about opportunities in “teaching or nursing or none of the above,” but “just didn’t feel right about not going to grad school,” she says.

So, in her senior year, she took tests that are required for admission to post-graduate schools: the GRE (general test for graduate schools), MCAT (for medical school), and LSAT (for law school)—and since the last one produced the best score, she “began to think about law school,” she relates.

|

|

|

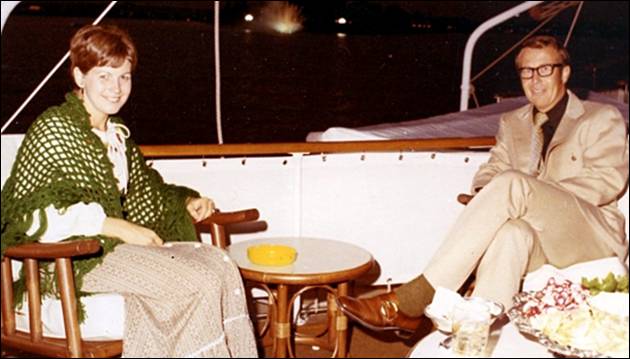

Aboard the Presidential Yacht Sequoia with husband John Tacha. |

She discussed the possibility with some professors, who she says were very encouraging. Her father, she recalls, was definitely not.

As a businessman, she says, “his experiences with lawyers were anything but pleasant.” And when he realized she was serious about it, she recounts, “he showed up at the door of my sorority” and spent “several hours” trying “to talk me out of this crazy decision,” finally asking in exasperation:

“Why would you pick something you can’t possibly succeed at?”

By this time, of course, she was completely convinced she was making the right decision. Her father, she says, had to retreat to a secondary position, seeking an assurance she would at least stay at KU—from which both her parents and all three of her sisters also graduated. When she indicated maybe not, he retreated again, to “well you’ll at least go to a state university, won’t you?”

This was 1968, after all, and he certainly didn’t want his daughter going “to some place like Harvard, with all those rabble rousers,” she quips.

So she went to the University of Michigan, which was “in the vanguard” of issues like affirmative action and civil rights, and where she received “a wonderful legal education.” But while other high-achieving students were headed off to judicial clerkships and big firm opportunities, the glass ceiling was very much still in place, she recalls.

Goes to Washington

Someone suggested she apply to the White House Fellows program, which places young professionals in yearlong, fulltime salaried positions as special assistants to high-ranking members of the administration. Tacha was chosen and assigned to work for James Hodgson, who headed the Department of Labor from 1970 to 1973.

The experience turned out to be “life changing,” she says. She was introduced to the world of high-level public policy, and got to work with some of the “giants” who were shaping U.S. labor relations and labor law, including George Schultz, who had preceded Hodgson at Labor before becoming director of the Office of Management and Budget; Michael Moskow, a leading labor economist who held several senior positions in the Nixon and Ford administrations and later headed the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago; and W.J. Usery, who served as an assistant secretary and later headed the Federal Mediation and Conciliation Service.

She credits the fellowship with enabling her to experience “all sorts of management styles” and meet “all these important Californians” associated with President Nixon, such as Charles “Tex” Thornton, the head of Litton Industries and a major donor to Pepperdine, as well as to Stanford and USC. Hodgson, a Minnesota native, had important ties to California too, having worked at Burbank-based Lockheed Aircraft Co. for 30 years before joining the government as Schultz’s deputy.

She completed her fellowship in August 1972, and was offered a permanent position in the department’s Manpower Division. But she also received an attractive offer to join a major D.C. law firm, Hogan & Hartson—later merged into Hogan Lovells—which had few women attorneys at the time.

Her tenure there was short, however, because her boyfriend, a small town high school basketball coach named John Tacha, had no intention of moving to the nation’s capital. So she moved to Concordia, Kansas, took her home state’s bar exam, and got married.

If it was hard for a woman to get a job as a lawyer in a major city, she says—citing the examples of Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and retired Justice Sandra Day O’Connor—it was nigh impossible on the prairie. If she wanted to practice law, she explains, she was going to have to do it solo.

First Divorce Case

There was little about the corporate practice she worked in at Hogan that prepared her for Concordia, where she shared space with an older lawyer and took whatever cases she could get. She recalls her first divorce case.

“I’d prepared and prepared,” she says, and thought she’d asked her client every pertinent question. At least until the elderly judge made a helpful suggestion.

“Counsel, you may wish to ask her where she lives,” the judge said, gently reminding her that domicile was an essential element of a divorce action. She credits that jurist, Republic, Kansas District Court Judge Marvin Brummett, with helping shape her “judicial personality.”

Brummett, who spent his entire career in that rural jurisdiction—except for occasional assignments to the Kansas Court of Appeal—was “the old model of the local judge,” she says, and as a result, “my client never knew that I failed to do the obvious.” Asked in a 2004 interview what judges she most admired, she listed two—Plessey v. Ferguson dissenter John Harlan, and Brummett.

About six months later, she received an offer to teach part-time at KU law school, commuting three-and-a-half hours one day per week. And after one semester, she was offered a fulltime position.

Family Moves

It was a big step to take, one that required her husband to give up his teaching and coaching jobs and move to Lawrence. But the couple had agreed that they would take turns making big decisions, and it was her turn, she says, so they made the move.

“I knew it was going to be tough [practicing] in a small town,” she says. “Teaching was intellectually more promising and gave me the ability to remain legally engaged.”

|

|

|

With former University of Kansas Chancellor Robert Hemenway after receiving a Distinguished Service Citation. |

It also gave her a first taste of educational administration, as she was appointed vice chancellor for academic affairs “at a pretty young age,” she notes, although she continued to teach classes at the law school.

The move to Lawrence turned out well for her husband, also. He joined the Bureau of Lectures and Concert Artists, Inc. which supplies content for school assemblies—its most popular attractions these days are troupes of Chinese acrobats—and bought the company when his boss died in late 1974.

He still owns the business, and runs it from Lawrence.

The couple has four children, and her professional success, she says, would not have been possible without “a flourishing family.”

John Reece Tacha, who works in his father’s business, is the oldest child, followed by David Tacha, an insurance broker in Denver; Sarah Bergman, who lives in Portland, Ore. and teaches in nearby Vancouver, Wash.; and Leah Tacha, an artist who lives in the gentrifying Brooklyn, N.Y. neighborhood of Williamsburg and has exhibited around the country.

The artist explains on her web page:

“I was raised by a mother who was obsessed with color, glitter, and the shine of success, and a father who was inherently practical, hardworking, had a pointed sense of humor, and never missed a Kansas basketball game. The soundtrack to my morning breakfast was the ESPN theme song coinciding with my mother’s blaring Broadway Musicals.”

There are five grandchildren, she says, and while the family lives all around the nation, they gather for holidays in the winter, and in the summer, their home just outside of the Kansas college town becomes “Camp Tacha” for the youngsters, she says with a laugh.

Federal Appellate Bench

Her ascension to the federal appellate bench was more a product of timing than “thoughtful planning,” the dean says.

She received a call from then-U.S. Sen. Bob Dole, “a mentor and a wonderful friend” to this day, she remarks. Dole knew her family well—her mother had worked in his first congressional campaign and served on the Republican National Committee.

Dole explained that a new seat on the Tenth Circuit was set to go to a Kansan, and that she should consider putting herself forward for it.

She hesitated at first, she says. Her fourth child had just been born, and two prominent male lawyers were believed to be in contention for the post. But, “to make a very long story short,” she says, Dole told her that neither of them was going to be appointed.

So, she told Dole she would put her application in—with one caveat. She would only do it if she could maintain chambers in Lawrence.

Lawrence had no federal courthouse, and no one could recall a federal judge ever sitting there, she says. But when she made it clear to Dole that she would not take the job otherwise, she recounts, some quick research was done and revealed that many years earlier, Congress had made Lawrence an authorized place for holding court, meaning that the General Services Administration could rent space for her chambers.

That was good enough for Dole and the White House, and she was nominated by President Reagan in 1985. With the Senate in Republican hands and the staunch backing of Dole, the majority leader (and future Republican presidential nominee), and of the state’s other senator, Nancy Kassebaum, she was confirmed in a matter of weeks.

The process was “not nearly as contentious as it is today,” she observes.

The closest thing to a difficult question she had to answer at her hearing, she remembers, came from Judiciary Committee Chairman Strom Thurmond, R-S.C., who “asked how someone with a brand new baby” would be able to handle the duties of a federal appellate judge, including travel between Kansas and the court’s Denver headquarters.

She responded that she’d “had some very responsible positions, a very good spouse, and very good help,” which apparently satisfied the then-octogenarian Thurmond, as she sailed to confirmation.

She became only the second woman ever to sit on the Tenth Circuit, after Judge Stephanie Seymour of Oklahoma.

The two remain “the closest of friends to this day,” Tacha says. Both were appointed at relatively young ages, and Tacha followed Seymour as chief judge, holding the post from 2000-2007.

Wide-Ranging Issues

As a new jurist, Tacha says, she was fascinated by the diversity of the Tenth Circuit’s caseload. There were cases involving immigration and nuclear energy from New Mexico, public lands and Native American rights cases from around the circuit, and “a lot of great religious liberty cases.” There was also a great deal of death penalty litigation, as all six of the circuit’s states—New Mexico, Utah, Colorado, Kansas, Wyoming and Oklahoma—had capital punishment laws.

|

|

|

With Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg during a retreat for Tenth Circuit Judges. |

It was also the Tenth Circuit that upheld the first federal death sentence in four decades, that of Oklahoma City bomber Terry McVeigh.

It was, she says “the most collegial court,” with relations among the judges characterized by “a high level of mutual respect” and “precious few dissents.”

She “absolutely loved” being an appellate judge, she declares—“I never had a job I didn’t like”—but after completing her term as chief judge, she was thinking about new challenges. Realizing that “massive changes…were coming to legal practice and legal education,” she says, she began to “wonder if there was something at the margin I could do in legal education.”

Pepperdine Post’s Appeal

The Pepperdine job was especially appealing, she explains, because she’s had this “long and crazy relationship with California,” going back to those days in the Nixon administration, and some specific ties to Malibu and the school. Her old boss at the Labor Department, Hodgson, had retired to the area; the school’s past president, David Davenport, had been a student of hers at KU; and Davenport’s successor, Andrew Benton, is from Lawrence.

She also had a longstanding friendship with the previous dean, Kenneth Starr (solicitor general under President George H. W. Bush and independent investigator whose report led to the impeachment of President Bill Clinton) who had joined the D.C. Circuit around the time she came on the appellate bench and who she had worked with on various committees. She beat out four other finalists for the job and came aboard in 2010.

One of the great things about being dean of a law school, she explains, is that it has enabled her to branch off into other law- and education- related work. She cites, among other examples, the “very energizing” work that she has been doing on a task force, along with other sitting and retired judges, as well as education professionals, to restore civics education to its rightful place in the school curriculum.

Modern day political rhetoric, she says, “proves that the public doesn’t know much about government.”

Tacha was able to join her civic background and judicial experience as one of a number of American judges who worked with the State Department to bring Western notions of the rule of law to emerging nations. She helped draft a new constitution for Albania, which emerged just 20 years ago from its place as the last bastion of Stalinism, and has gradually moved closer to the West.

She recalls vividly her group’s discussion with the country’s young attorney general, on whom they tried to impress the importance of individual freedom of expression, in opposition to a proposal to ban ethnic minority political parties.

They easily fended off the attorney general’s qualms about conflict between such parties and the president or other leaders of the civilian government.

But the attorney general’s next question—“But what if the military comes after you”?—was not so easily answered, she recalls.

“No federal judge in the nation thinks about this,” she remarks.

Drop in Applications

As for her work at Pepperdine, she notes that she is presently addressing the impact of the precipitous drop in law school applications, about 40 percent from where it was when she arrived. All law school deans, she says, have been “in the catbird’s seat” when it comes to the debate over whether a legal education today is worth the debt that many students must take on in order to obtain it.

What is particularly distressing, she says, is that at Pepperdine, a faith-based school, many students want to go into public interest law, but find they can’t afford it, and there aren’t very many such jobs available. “It’s become very hard to do the kind of work that the public good needs,” she says.

The five years she has been at Pepperdine, she says, have “been among the most interesting years in the history of legal education,” as schools adapt to changes in technology, as well as to a completely new economic reality.

As for her own tenure, she says, she is uncertain how much longer she will remain at the school. “I’m not young, you know,” Tacha, who turns 70 this month, says with a chuckle.

But she will miss it when she leaves, she acknowledges. Although Kansas will always be home, she says, “I love the energy of the West Coast and I love the legal community” and the people who make up the school and Malibu.

It’s “wonderful…for an inland soul to wake up every morning and see the ocean,” she says, although she misses “the seasons, the leaves, and [KU] football.”

Whenever it ends, she says, it will have been a great experience.

“I’ve been the luckiest lawyer alive,” she remarks. “I’ve done it all.”

____________________________________________

Comment

This letter is in response to your request concerning Dean Deanell Tacha of Pepperdine Law School. Our Committee was presented with a real crisis after we obtained word that the then best Law School Dean in the United States was leaving Pepperdine to assume the position of President of one of the nation’s leading Universities, Baylor University. I will never forget a call from our Dean Emeritus, Ronald Phillips, on a Saturday night, alerting me that by Monday morning the media would have the story to the effect that our Law School Dean, Ken Starr, and his wife Alice were leaving Pepperdine; this was a real shock. The question was, how do we attempt to replace a person of Ken Starr’s international reputation as a brilliant, accomplished and warm human being? He was a Appellate Judge, Solicitor General of the United States, successful Prosecutor and accomplished Dean of one of the best law schools in the U.S. The situation indicated that replacing him was going to be a huge task.

We interviewed eight highly qualified persons for the job. A review of Judge Tacha’s Curriculum Vitae, accomplishments and personal interviews was more than sufficient to qualify her for the job.

The amount of time that Dean Tacha spends on behalf of Pepperdine Law School is almost unbelievable. Night and day—she is a twenty-four hour, seven-day-a-week workaholic. Her home is actually a public meeting place for all at Pepperdine Law School; her schedule on evenings and weekends is taken up with devotion to the betterment of the school. You might find her in Washington, D.C. or any place between here and there as an ambassador for Pepperdine Law School.

The times that have caused me to be most proud of Dean Tacha were at any speaking engagement, and especially the ones at a legal club in Los Angeles that annually not only invites all of the California Supreme Court Justices (who usually attend) but also invites all of the local Southern California Law School Deans. All eight or nine deans give a presentation about their individual law school and their thoughts for the betterment of the practice. Time after time, if the “applause meter” means anything, Dean Tacha’s presentation is always met with the loudest enthusiasm.

Just as when our committee nominated Dean Emeritus, Ronald Phillips, to be the first Dean of Pepperine Law School at Malibu with his tremendous accomplishments as far as putting Pepperdine Law School on the map, I am very proud of the fact that I was again a part of the committee selecting an outstanding Dean for Pepperdine Law School.

JOHN L. MORIARITY

Moriarity & Associates

Copyright 2016, Metropolitan News Company