Thursday, December 22, 2016

Page 8

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

How Far Has LACBA Come in the Past 50 Years?

By ROGER M. GRACE

Fifty years ago—to be precise, in March 1966—the Los Angeles County Bar Association’s monthly “Bar Bulletin” (forerunner of Los Angeles Lawyer) contained a column by President Glendon L. Tremaine which notes:

“The Los Angeles County Bar Association had 1,207 members in 1923, by January of 1966, it has over 6,000.”

LACBA had, in that 43-year period, roughly quintupled the number in its ranks.

If the association now had five times the number of members it did in 1966—after 50 years, not 43—it would be 30,000 strong. It isn’t.

Despite a burgeoning lawyer population in this county, LACBA has slightly less than twice the number of paid lawyer members that it had a half century ago.

The membership was formerly higher than it is now; the association is steadily losing members. That does evidence that it has been doing things wrong—something widely perceived by those who cast ballots in the last election for officers and trustees, giving approval to a reform slate.

And it’s been losing money over the past several years, about $1 million a year, with this year’s loss projected at as high as $1.2 million. Obviously, the drop in membership heavily contributes to loses owing to diminished revenues from dues.

![]()

Contrasting LACBA’s total membership of today with the number in 1966 is an apples-and-oranges comparison.

As to the current figures, LACBA Director of Communications Jason Ysais told me last Friday, in an email:

“LACBA membership fluctuates throughout the year. Since it runs a membership campaign from September through January of each bar year, the number of members in any given month can fluctuate by thousands. December is typically our highest renewal month, but many of our regular members will renew in January and February of next year. As of the beginning of December, our membership was 18,000. This number will increase through February. If we decide to host the New Admittee Reception this spring, the membership will increase again. At this time no decision has been made on holding that event.”

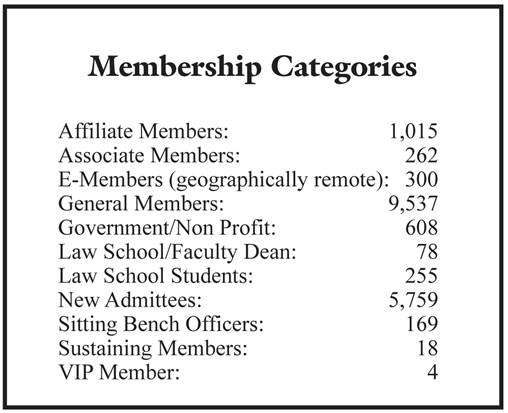

The exact total membership now claimed is 18,005. However, this includes non-lawyer “associate” members, law students, and a horde of non-dues-paying new admittees.

When you tally the number of dues-paying lawyers, it’s 11,560. If you add judicial members, the figure is 11,729, but that includes bench officers outside Los Angeles. That category even includes jurists outside the United States.

Noteworthy is that LACBA’s present claim of 18,000 members, overall, contrasts with its boast of 24,000 members one year ago, at a “study hall.” That was a meeting staged by then-President Paul Kiesel in a vain effort to placate leaders of the sections incensed over LACBA policies. So, from December of 2015 to December of this year, did LACBA actually lose 6,000 members?

LACBA’s current President, Margaret P. Stevens, yesterday clarified this. She says the 24,000 figure was a “rough approximation” that had been used “in prior years,” and there has not actually been a “drastic drop-off in membership since last year.”

![]()

Rendering a comparison all the more difficult is that in 1966, not all persons licensed by the State Bar who desired membership in the County Bar were eligible for admission…and even those who were eligible could be blackballed.

While LACBA did provide information in response to my Dec. 5 request, it says it hasn’t yet laid its hands on the bylaws in effect in 1966—which would reflect precisely requisites for membership then. However, John D. Taylor, a leading probate practitioner and LACBA president in 1978-79, in response to an inquiry, kindly attempts to fill in the blanks, while cautioning that it’s “from my memory which may not be 100% accurate.”

He says that in 1966, to be a member of LACBA, “you had to be a judge or member of the State Bar of California and reside in or have an office in Los Angeles County (it may have a little larger geographical area).”

|

|

|

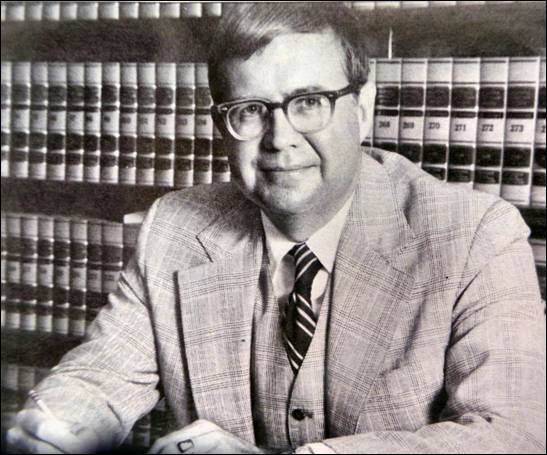

This photograph of Pasadena probate attorney John D. Taylor appeared in the Los Angeles Lawyer magazine in 1978 and 1979 in connection with his “President’s Page” column. |

Even that might not have been enough. Applicants had to be approved by the Membership Committee and the Board of Trustees.

Their names were published in the Bar Bulletin (in earlier days, they were posted for two weeks on the Los Angeles County Law Library bulletin board). The Bulletin routinely advised that any member could submit information “that would be of value,” with absolute secrecy being accorded the communication.

(Among the 90 applicants listed in the March 1966 Bar Bulletin, I recognize 12—and there are probably others—as persons, some now deceased, who went on to become judicial officers. One applicant listed is Arthur Gilbert, currently the Court of Appeal presiding justice of this district’s Div. Six. Among others are Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Richard L. Fruin Jr, and former members of that court, Michael Farrell, Keith L. Groneman, Charles E. Jones, Edward Kakita, Sherrill Luke, and Jack Newman. And there are three who went on to serve (or perhaps “disserve” would be more accurate) on the Superior Court: Richardo Torres, Edward M. Ross, and David Aisenson. LACBA applicant Michael Yelovich was to become a member of the Los Angeles Municipal Court.)

![]()

Taylor recites, in an email, that around 1964, he and attorney John Hussey (now retired) joined the Membership Committee. He recounts:

“At the first meeting Hussey and I attended, the then Executive Director Stan Johnson handed each us 5 or 6 large recipe type cards. Each card had the name of an applicant and whatever I assume the Executive Director or someone thought we should know about applicant. We sat around and read the cards and then reported to other members of the Committee what we had read. I asked the Chair if we could have the cards sent to us before the meetings—that would save everyone some time. Stan Johnson said that absolutely could NOT be done. The information was highly classified and the cards could not leave the room.

“Not long after that the name of an attorney who was well known for defending pornography cases came up. The Chair said ‘I don’t want anyone who defends pornographers to be a member of my club.’ At a meeting or two later, after canvassing other members of the Committee, either Hussey or I made a motion, which carried, recommending to the board of trustees that the Membership Admission Committee be abolished and that any judge or member of the State Bar of California in good standing was entitled to membership (subject to geographical location). The trustees accepted our recommendation and abolished the Membership Admissions Committee. You may wonder why I am mentioning this. It is because if I have done anything for LACBA and the legal profession, it was my perhaps small part in doing away with the Membership Admissions Committee which at least in the past had black balled membership to Jews, African Americans, Hispanics, Asians, defenders of porn, etc., or so I was told.”

|

|

|

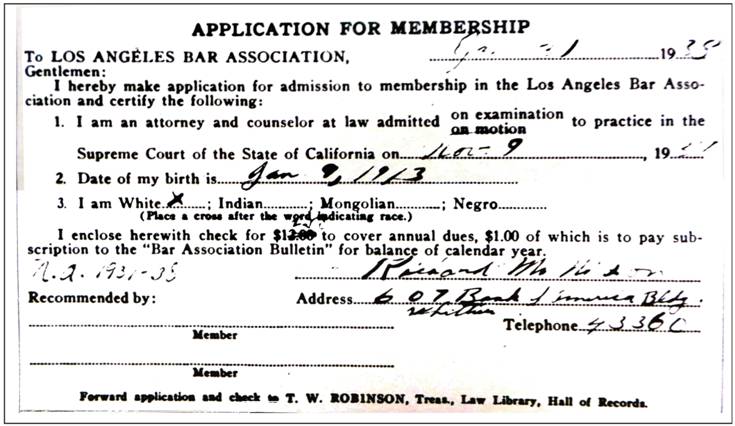

Above is the January, 1931 application for membership submitted by Whittier attorney Richard M. Nixon. There were no categories of membership. The organization then inquired as to race, not admitting African Americans until 1950. |

So, comparing the raw number of dues-paying lawyers in LACBA in 1966 with those who are now in the ranks would not take into account that every lawyer who can join the association at this stage could not have gained membership then. That is to say, that if today’s admissions practices had been in effect in 1966, there would in all probability have been significantly more than 6,000+ dues-paying lawyer members, so that any comparison is, necessarily, skewed.

What can be said is that paid lawyer membership now is less than double the figure a half century ago,

There appears in a box below a break-down of categories into which the current members fit.

|

|

![]()

Below are membership figures for particular years, with the source of the information indicated.

However, as noted, there are now categories of membership that are relatively new.

When the organization was founded in 1878, and resuscitated in 1888, its membership was comprised solely of Los Angeles lawyers. Its 1888 constitution—then the organization’s governing instrument, supplemented by bylaws—provided: “Any attorney and counsellor of the Supreme Court of the State of California of good standing, may become a member of this Association, after being duly elected, as hereinafter provided.” Its 1923 constitution was to like effect, and—perpetuating what was already the rule—said that a judge or justice could be an “honorary” member, paying no dues.

Gradually, new categories were added, and judges were required to pay.

Taylor recalls:

“During the second half of my presidency, we amended the bylaws to provide that any judge in the United States or any person who was a member in good standing of any state bar in the United States or the District of Columbia could become a member of LACBA. At least part of the reasoning was to permit in house corporate attorneys, corporate executives, trust officers, law professors (e.g. I don’t think [torts authority William] Prosser ever became a member of the State Bar) etc. to become full fledged members of LACBA.”

He says the notion of allowing laypersons in the organization “was discussed.” That, however, was to come later.

“There were approximately 15,000 members of LACBA in 1978-79 who were attorneys or judges,” he recalls.

Nowadays, virtually anyone in the world can become a LACBA “associate” member, a category of persons who are not licensed to practice law anywhere in the United States but have “an interest in the work of the Los Angeles County Bar Association.”

The whopping figure LACBA claimed in 2009 doubtlessly includes non-dues-paying members (new admittees in their first year, and perhaps others) while the totals for succeeding years are from a report on the numbers of paid members.

Ideally, the figures below for each year would each reflect the number of members as of the same month and day. They don’t, having been culled from various sources.

Fluctuations in membership through the course of a year, alluded to by Ysais, is evidently nothing new. The figure appearing below for 1970 is 9,500, which comes from the October issue of the Bar Bulletin. But the number had been higher a short time before.

Seth Hufstedler, who is “senior of counsel” to Morrison & Foerster, would know. He was LACBA president in 1969-70 (and State Bar president in 1973-74). He advises that during his LACBA chieftainship, “the 10,000th member was admitted,” noting: “I welcomed her.”

(He says she was the daughter of Homer Crotty, a member of the law firm of Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher, whom Hufstedler termed “a good friend and great lawyer.” Crotty, now deceased, was president of the State Bar in 1950-51. Daughter Anne Lloyd Crotty, who practiced in Pasadena, is now an inactive State Bar member.)

1912: 511. (Los Angeles Bar Association Year Book, 1913.)

1917: 560. (“Centennial Pictorial Membership Directory,” 1978.)

1923: 1,226. (American Bar Association Journal, November.)

1928: 2,454. (The Bar Association Bulletin, March 1.)

1940: “about 2000.” (American Bar Association Journal, January.)

1948: 2,261. (Bar Bulletin, April.)

1959: “4000 strong,” with “the entire legal profession of Los Angeles County” numbering 9,000. (“Lawyers of Los Angeles,” book published by LACBA.)

1961: “more than 4000.” (Rolling Hills Herald, March 2, 1961.)

1968: “in excess of 7,400.” (Bar Bulletin, July.) It was then “the third largest bar association in the United States.” (“Centennial Pictorial Membership Directory, 1978.)

1970: 9,500. (Bar Bulletin, October.)

1975: 12,000. (Los Angeles Times, March 14, 1975.)

1978: 15,000. (LACBA “Centennial Pictorial Membership Directory.”)

1984: 17,000. (Los Angeles Times, July 9, 1984, noting that Los Angeles’s “County Bar Assn…debates with Chicago as to which is the nation’s largest.”)

1988: 25,000. (Los Angeles Times, Aug. 28, 1988 “letter to the editor” from then-LACBA President Margaret Morrow.) A differing figure: “[I]n excess of 23,000” (ABA Antitrust Law Journal, text of remarks by Patrick E. Higginbotham, judge of the Fifth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.)

1995: 21,000. (Los Angeles Lawyer, October.) A differing figure: 22,786. (“Bar Associations: Policies and Performances,” Yale Law & Policy Review, 1996.)

2009: “over 30,000 members.” (LACBA press release, billing the organization “the largest local voluntary bar association in the nation.”)

2011: 16,970. (Section and General Paid Membership Report, LACBA internal document, 2016.)

From there, the numbers have steadily waned. The 2016 membership report, showing paid members, reveals:

2012: 16,234; 2013: 15,596; 2014: 14,666; 2015: 13,482; 2016: 12,161, as of July 29.

The New York City Bar Association claims a membership of more than 24,000. Membership is open to “any attorney in good standing admitted to any jurisdiction in any state or country..., as well as recent law school graduates and law school students that are enrolled in good standing at an ABA-accredited law school.”

The Chicago Bar Association is second, with 21,000 members. But it, like Los Angeles, has non-lawyer “associate” members.

The number of non-lawyer members of LACBA, Ysais relates, is 517, in the categories of associate members and law students. There are also non-lawyers among educators and government/nonprofit lawyers, and judges outside the state who are not members of the State Bar of California.

![]()

The August, 1965 “President’s Page” column by Edward S. Shattuck in the Bar Bulletin offers these thoughts:

“With 6,000 members now, we cannot help but look for the reasons why we do not have many more. To be admitted to membership in the Los Angeles County Bar Association is an honor. Yet there are many lawyers in Los Angeles County who should be members and are not….

“The effectiveness of our Bar Association depends on the interest of our members, the care with which we plan and the manner in which our leadership assumes and discharges its responsibilities.”

With less than 12,000 attorney members now, LACBA needs to reflect on why there are so few. It is largely because the interest of the membership in recent years has waned. With a sharp cutback in the number of events that are staged and outrageously escalated prices for those that do take place, LACBA has less and less to offer its members. The root causes are a lack of care in the planning and defective leadership, much of that leadership having been exerted by the paid CEO, Sally Suchil, whose regime, thankfully, ends next month.

Shattuck notes: “Each section runs its own affairs.” That isn’t true anymore, and this has been a major source of discontentment. Perhaps with the downfall of the Suchilocracy, bullying and micro-managing of the sections will end, facilitating the revitalization of LACBA. Stevens has evinced a desire to work with the sections.

Tremaine’s column says:

“As you can well imagine our office staff and quarters have increased in size, we have an able executive director in Stanley Johnson, the staff which does an excellent job has grown to a total of 13, plus our Public Relations Consultant.”

LACBA now has a CEO and Ysais is roughly an analogue of a public relations person. LACBA was able to operate with proficiency in 1966, with 13 employees, in addition to its chief of staff and PR person; its total membership (using the figure of 18,000, which includes persons in categories not needing much staff attention) is now three times what is was then; it follows that it should be able to function now with 39 employees, not counting Suchil and Ysais.

How many employees does it actually have, excluding those two? According to information provided by Ysais: 72. And, he says, in addition to seeking a replacement for Suchil, it has an opening for an events administrator.

(It should be noted, however, that the staffing level is down from what LACBA has had in the past. Example: There were 95 employees, according to a 1995 American Bar Association inventory. But then came the recession. “In response,” President, Alan K. Steinbrecher says in the “President’s Page” column in the July/August, 2010 edition of Los Angeles Lawyer, “the Association’s leadership has acted proactively to reduce costs in a number of ways, including instituting salary and hiring freezes….”)

The Beverly Hills Bar Association, by the way, has nearly 6,000 members and about 18 employees, and is in the black.

Shattuck’s 1965 column reports that the annual budget was $125,000; Tremaine’s column, the following year, says it was “in excess of $150,000.”

This year, the budget reflected anticipated revenues of $12.6 million, anticipated expenses of $13 million, and a deficit of $267,809—with the deficit now projected to be substantially higher.

![]()

At a Dec. 13 meeting of the Council of Sections, Margaret Stevens pledged to propose a “balanced budget” at next month’s meeting of the Board of Trustees. That would be a welcome departure from the past few years.

Whether the anticipated revenues and expenses will be realistic, however, is another matter.

In the first six months of her administration, Stevens has substantially increased access to LACBA’S financial reports and governance documents, and staged a successful retreat at which officers got together with section leaders and a “facilitator.” With her backing the move, as of the end of June, LACBA will be eliminating the Civic Mediation Project, which has been a financial drain.

But with membership dwindling and the deficit rising, that just isn’t enough. Abandoning all of its eleemosynary projects might well be a necessity.

Stevens was part of the leadership that was, as of a year ago, seemingly oblivious to the financial crisis the organization is in. Most all of the Nominating Committee’s choices for officer and trustee position were opposed by a reform slate, put together by the newly formed Council of Sections, headed by past LACBA President John Carson. All of the reform candidates won handily. Stevens ascended to the presidency on July 1 because succession to the top spot was automatic for the president-elect.

The 2016-17 president-elect, Michael Meyer, has apparently instilled in her an awareness that there is an emergency. Yet, but tiny steps have been taken by her administration, so far, to restore LACBA to solvency and credibility. What counts is that a determination does seem to have developed on Stevens’ part to accomplish that goal.

It is to be hoped that in the second half of her administration, beginning Jan. 1, she will orchestrate bold measures, and emerge a hero.

Copyright 2016, Metropolitan News Company