Thursday, July 14, 2016

Page 9

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

U.S. Attorney’s Office Acts Viciously in Seeking Incarceration of Ex-Sheriff Baca

By ROGER M. GRACE

Former Los Angeles County Sheriff Leroy D. Baca is a 74-year-old man who has devoted his life to law enforcement and is in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease. He made a blunder: he told federal investigators (not under oath) that he did not know of certain efforts within his department to impede an FBI investigation of conditions in the Men’s Central Jail, but did.

In light of all of the circumstances, he should not be imprisoned for that.

His offense was slight. His lack of “dangerousness” is manifest. His record of public service is glistening.

Yet, callously, the Office of United States Attorney is urging that U.S. District Court Judge Percy Anderson impose a six-month prison term on Baca when he is sentenced on Monday for a violation of 18 USC §1001—that is, making a false statement to federal authorities. His mistruth was spoken on April 12, 2013, during a five-hour interview conducted by the U.S. Attorney’s Office in the office of his then-attorney.

Baca, four times elected sheriff, served in that capacity from Dec. 7, 1998 until his resignation on Jan. 31, 2014. He pled guilty, last Feb. 3, pursuant to a plea bargain under which he could be sentenced, in conformity with federal guidelines, anywhere from zero days to six months; if the court were inclined to impose a sentence greater than six months, he could withdraw his plea.

![]()

Whether Baca should even have been charged is questionable.

He was not implicated in the obstruction of justice and the conspiracy to obstruct justice which former Undersheriff Paul Tanaka orchestrated, and for which Tanaka was convicted and sentenced to five years in prison. Baca was not connected to the beatings of prisoners by deputies, or to bribery or other misdeeds, which led to convictions of 21 members of his department.

Rather, in the 2013 interview, occurring after the misconduct took place that led to the convictions, Baca falsely disclaimed knowledge of certain matters. His misrepresentation was lamentable but in no way prejudiced the actions against the guilty parties.

Putting it in perspective, while Tanaka was overseeing day-to-day operations of the department, Baca was occupied with broad administrative tasks, such as creating and implementing programs—commendable ones—aimed at educating inmates and otherwise preventing criminality.

Perhaps he should have been more closely in touch with what was going on in the department, but any failure in that regard is hardly criminal in nature. He tended to look at the broad picture and was clearly not subject to being accused of micro-managing.

It might well be suspected that the prosecution of Baca was spurred by improper motives. The U.S. Attorney’s Office can now boast that it gained a conviction of the immediate past Los Angeles County sheriff. It can avoid allegations among the ill-informed that while the ex-undersheriff was sent to prison, it accorded deference to the former top man in the department by not levelling charges against him.

While this is mere speculation as to the motivation behind the prosecution of Baca over his relatively minor misdeed, what is quite clear is the unjustness of a call for his incarceration.

U.S. Attorney Eileen M. Decker of the Central District of California displays cold-heartedness, if not ruthlessness, in seeking to have Baca cooped up with haters of law enforcement. Due to his physical and mental frailty, he would be vulnerable to likely assaults.

Decker’s exhortation—in position papers signed by Assistant U.S. Attorney Brandon Fox—that Anderson make an example of the former sheriff would entail a disregard of federal sentencing criteria. It would depart, also, from the concept of “equal justice under the law” by saddling Baca with sterner treatment than would often be visited upon a first offender who had inflicted physical harm on a victim or caused financial deprivation of a prey.

![]()

In a position paper on sentencing filed last Thursday, Fox insists that Baca’s medical condition is not germane because “[t]he Bureau of Prisons currently houses approximately 300 inmates with more severe forms of cognitive impairment resulting from dementia or Alzheimer’s disease” and declares that Baca would receive appropriate treatment.

But of those 300 inmates, how many committed offenses so minor as Baca’s, and how many had a sterling record of public service, as opposed to a record of criminal offenses?

|

|

|

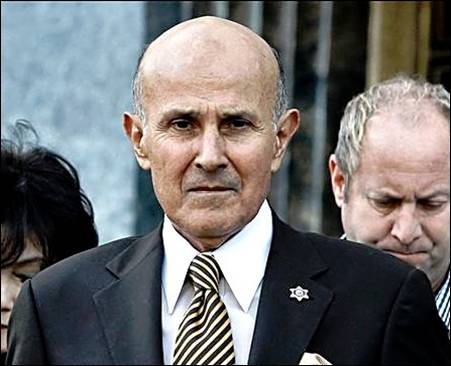

—AP LEROY D. BACA Former Sheriff |

Fox dismisses the notion that Baca would face danger in a penal institution from inmates, declaring:

“[D]efendant claims that his condition and past career make him susceptible to abuse while in custody. However, the Bureau of Prisons houses many well-known inmates.”

That misses the point and comes close to being smart alec in nature. It’s not that Baca is “well-known” that renders him a likely target. A rock star or a major league athlete might be “well-known,” but that factor would not be apt to engender enmity toward him or her on the part of other prisoners. That Baca had been a law enforcement officer would, foreseeably, alone stimulate hatred on the part of much of the prison population. The fact that he served at the highest station in the state’s largest county law enforcement agency—no doubt responsible for the apprehension of some of the federal inmates in connection with previous state crimes—would surely boost the prospect of bodily harm being inflicted on him.

Yet, Fox continues:

“Based on the type of facility that defendant likely would be assigned to, he will not be encountering violent criminals.”

Note the word “likely.”

Can it reasonably be supposed that in any prison, those confined with Baca would be gentle souls, sitting around listening to classical music, trading recipes, and debating free will versus determinism?

And are Decker and Fox going to vouch for the passive nature of all of the inmates with whom Baca might come in contact?

![]()

The prosecution’s initial position paper on sentencing, filed June 20, says:

“A sentence that provides for specific and general deterrence is necessary. Instead of upholding the law, defendant Baca committed a crime by lying to the federal government. Baca’s actions showed that he believed he was above the law. This was the same attitude exhibited by other Sheriff’s Department officials involved in the offenses.”

The sentencing guidelines, contained in 18 U.S.C. §3553(a), do list as one purpose of a sentence, affording “adequate deterrence to criminal conduct.”

So far as “specific deterrence” (often denominated “special deterrence”) is concerned, can it seriously be postulated that Baca needs to be incarcerated for six months in order to dissuade him from again lying to federal authorities? Let’s be realistic. Fox’s reference to a need for “specific deterrence” is plainly asinine.

With respect to general deterrence, the disgrace which Baca has suffered in standing convicted of a felony will no doubt deter the telling of mistruths to federal officers by persons in the future, for there is now, by virtue of news accounts, enhanced public awareness that such conduct does constitute a punishable offense. Leniency in sentencing Baca would not detract from that awareness because few who might be charged with the crime in the future could possibly point, as Baca can, to the lack of prior misconduct and, in fact, to meaningful feats in enhancing the public’s welfare.

![]()

In any event, deterrence is only one factor in sentencing.

The first ones listed in the federal statute are “the nature and circumstances of the offense and the history and characteristics of the defendant.”

Baca made no secret in 2011 of being peeved over the FBI probing jail conditions without his knowledge. He desired an investigation of jail conditions, over which there was an emerging concern, but simply wanted to clean his own house. Baca publicly noted that providing a cell phone to an inmate—which the FBI did, in the course of gathering evidence—is a crime, under California law. The then-sheriff authorized threatening the special agent in charge of the investigation with arrest. The inmate, an FBI informant, was, after his cell phone was uncovered, kept incommunicado from federal investigators.

In the 2013 interview (not a deposition) at his attorney’s office, Baca falsely disclaimed knowledge of the denial of FBI access to the whistleblowing inmate or of attempted intimidation of the special agent.

It was, of course, wrong for Baca to lie; he admits that. It could be observed that if every public official who lied were put in prison, there would be few to run the government, but it remains that the particular lie did contravene a federal statute.

However, Baca’s lie did not hinder any investigation. Whether Baca knew or did not know of the attempt to block the FBI from communicating with an inmate and to bully a special agent could have had no effect on the prosecution of those directly involved. In failing to admit a lapse in judgment, he was not seeking to avoid an admission of complicity in crimes, of which he was suspected; Baca had been assured that he was not personally the subject of the investigation.

The overriding factors in Baca’s case are “the history and characteristics of the defendant.” Baca—honored by this newspaper in 1999 as “person of the year” and feted by countless others—has served in the Sheriff’s Department since 1965 and, as sheriff, developed innovative programs that reflected compassion and dedication to the goal of blocking paths to criminality. His role has been that of a hero, not a miscreant.

Another sentencing factor is protecting “the public from further crimes of the defendant.” Baca is not a man of criminal bent. He is a “crime-fighter,” not a crime perpetrator. It would have been unimaginable that he would commit any future crimes, even if he had not been afflicted with Alzheimer’s disease. In light of that disease, any allegation of dangerousness would be ludicrous.

An objective, under the statute, is “provide the defendant with needed educational or vocational training, medical care, or other correctional treatment in the most effective manner.” Baca is not in need of being taught a trade, and what medical care he needs can be obtained at home or in facilities where treatment would be bound to be superior to that available in a prison.

The remaining goals are “to reflect the seriousness of the offense, to promote respect for the law, and to provide just punishment for the offense.” If promoting “respect for the law” means discouraging criminal conduct by others, it is duplicative of the provision on deterrence. If taken in a broader context, a legal system that is overly harsh draws fear, not respect. The offense, in context, is far from a serious one. And it would be unjust in the extreme to subject a 74-year-old man with a progressive mental disease, who has served the community admirably for half a century, to jailing.

The prosecution’s quest to vanquish a man who has lost his position in government and his reputation, and faces the certainty of a progressive loss of his mental faculties is, as I see it, despicable.

![]()

Among the hundreds of letters to Anderson urging that Baca not be incarcerated—from persons including former Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger, Los Angeles County Supervisor Don Knabe, former Los Angeles County District Attorney Steve Cooley, and former Assembly Speaker Bob Hertzberg—is a letter from the defendant’s wife, Carol Baca.

She tells of the myriad of programs he instituted, his dedication to his job, his generosity to those in financial need, and his steady memory loss.

A portion of her 5,803-word letter will appear in tomorrow’s issue.

Copyright 2016, Metropolitan News Company