Thursday, January 14, 2016

Page 4

PERSONALITY PROFILE:

MICHAEL NASH

Hard-Charging Prosecutor Becomes a Champion for Children

By KENNETH OFGANG, Staff Writer

|

W |

hen Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Michael Nash announced his plan to leave the court two years ago, after nearly three decades as a judge and 16 as head of the juvenile court, tributes were heard throughout the juvenile justice community, and even on the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives.

Nash, Rep. Tony Cardenas, D-Los Angeles, told his colleagues, is “an incredible man” and “a champion for children and families,” who deserved congratulations “on his well-earned retirement.”

Many would agree with Cardenas on the superlatives. The retirement part, on the other hand, “I clearly flunked,” Nash says.

At 67 years of age, and with various ailments—he has had multiple knee and shoulder surgeries, limiting the athletic lifestyle he had enjoyed since childhood—he accepted an invitation from his successor as presiding judge, Michael Levanas, to return to the courtroom, this time as a part-time delinquency judge.

Beginning this month, however, he has embarked on what some would call “mission impossible”—to forge cooperation among all of the county’s offices and agencies that provide services for children, as the first head of the Office of Child Protection. And after winning every conceivable local, state, and national honor that can be bestowed on a juvenile court judge, he remains as passionate as ever, he says, about his work.

He recounts a childhood very different from those of most of the children who have come through the courts, and those whose wellbeing he is now charged with protecting.

He grew up in the Inwood neighborhood, in Upper Manhattan near Ft. Tryon Park and its famed Cloisters. His father was a postman, and he and his younger twin brothers—Lloyd Nash is a Los Angeles Superior Court judge, Paul Nash a school principal in the Seattle area—attended local public schools.

Moves to Hollywood

In 1960, however, his father made “an impulsive decision” to leave the East Coast for California. The future judges’ father obtained a transfer, and they took up residence in the Hollywood area.

Nash was told at the time, he says, that “you can leave New York, but it will never leave you.” But the adjustment to a new school and new community was easy, he recounts, largely because of friends he made playing sports.

After graduating from Fairfax High School, where he played wingback on the football team, he enrolled at UC Santa Barbara, before transferring to UCLA.

“I had some crazy notion that I was having too much fun, and it was time to get more serious about school and life,” he says, explaining the transfer.

But he had made good friends at UCSB, and returned often to visit. In fact, he was sitting “across the street with some friends” on Feb. 25, 1970 when a group of students, protesting the Vietnam war and the firing of a leftist professor of anthropology, burned down the Isla Vista branch of the Bank of America.

Nash majored in political science at UCLA, although that wasn’t anything he particularly planned, he says. He thought he was going to major in economics, but under the system in place at the time, he explains, a student had to get on line to sign up for classes, and the economics line was too long, so he chose “poli sci” instead.

He didn’t have a firm career goal during most of his college career, he notes, but enjoyed working with young children and thought of becoming a teacher. But when he was close to graduation, he says, he discussed the idea with a professor who suggested he might find it frustrating, so he applied to law school as some of his friends were doing.

Enters Law School

He was accepted at Loyola Law School, which he terms “one of the great things that ever happened to me.” Not only did he get a law degree, he explains, but he made many “fairly significant” relationships there, starting with the first day, when he met Patricia Clemens.

|

|

|

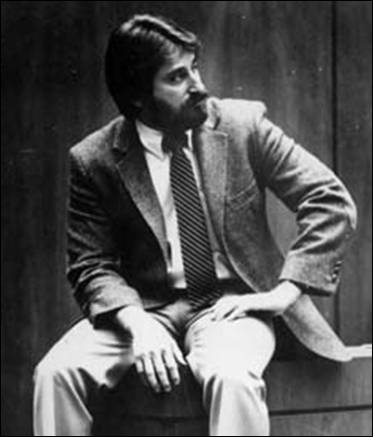

Sitting on the witness box after the Buono verdict. |

Nash and Clemens—who spent more than 30 years in the Los Angeles City Attorney’s Office before retiring—have been married for 31 years. She is now a part-time administrative hearing officer for the city.

Their daughter, Molly Nash, is thus far resistant to following her parents and other family members into the legal profession.

Nash also spent six years as a military reservist, from 1968 to 1974. One of his assignments was to assist morticians who were preparing the bodies of soldiers killed overseas for burial.

It was “as close to war as I ever want to get,” he says. It was also a strong contrast with his last assignment, after he had taken the bar exam, which was to oversee a base laundromat “with World War II machines that no one knew how to use,” which was probably why he only had one customer.

And then it was on to his legal career.

As he prepared to graduate, Nash explains, he took a clerking job in the legal department of a title insurance company downtown. One of the lawyers there did some appellate work, which Nash took an interest in, leading him to apply to the state Attorney General’s Office.

“I was fortunate to get hired there,” he reflects, and soon became engrossed in criminal appeals, arguing before the Court of Appeal and the state Supreme Court, which had quite the liberal bent at the time.

“We lost lots of cases” there, Nash recalls, but he gained a lot of valuable experience.

His personal politics, he recounts, shifted during the period as well.

Changes Parties

“I was born and raised a Democrat,” he says, but he was “heavily into law and order,” switched parties, and signed up to help then-state Sen. George Deukmejian, R-Long Beach, a staunch supporter of the death penalty, in his 1978 campaign for attorney general.

“I thought he was the right person for the job,” Nash remarks.

Deukmejian, a former MetNews Person of the Year himself, “is one of the nicest men and most decent politicians” and has been “wonderful” to him in his career, the ex-prosecutor says.

Nash discloses, however, that he recently returned to the Democratic Party.

“The Republican Party of the last few years has really gone off the rails,” he says, adding that he hasn’t “been voting for Republican candidates for years.”

While he handled his share of criminal appeals, like the other deputies in the office, he had an unusual opportunity to do trial work as well, he relates.

In 1978, he recounts, Johnnie Cochran—who went on to fame as lead defense counsel in the O.J. Simpson murder case and handled other high-profile cases before his death in 2005—left private practice for a time to become a top administrator under then-District Attorney John Van de Kamp. The office then had to conflict out of all of Cochran’s cases, which were assigned to the attorney general.

“I apparently did well enough” in handling those cases, Nash says, because he would soon be assigned the case that would become his “life changer.”

Hillside Stranglers Case

On July 13, 1981, the District Attorney’s Office moved to dismiss the 10 murder charges against Angelo Buono, one of two “Hillside Stranglers” ultimately proven to have kidnapped, raped, and killed young females—their ages ranging from 12 to 28—in the Hollywood-Glendale area.

The dismissal motion was made on the ground that the case could not be won, a conclusion prosecutors reached after a yearlong preliminary hearing. Jurors, they said, would never believe the prosecution’s chief witness: Kenneth Bianchi, Buono’s cousin and the other member of the Hillside Strangler duo.

Bianchi, after being arrested in the state of Washington for murdering two girls, confessed to his role in Buono’s crimes and agreed to testify against his relative in exchange for being spared the death penalty.

Then-Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Ronald George, later the state’s chief justice and now retired, denied the motion and ordered the case transferred to the attorney general for prosecution.

Nash and now-Court of Appeal Presiding Justice Roger Boren—who had joined the office just a year before Nash—were assigned to review the evidence. They met with several experienced prosecutors, and the group decided the case could, in fact, be won.

‘Go for It’

He and Boren, Nash recalls, assumed at the time that more experienced prosecutors would be assigned to try the case. But when they met with Attorney General Deukmejian to explain their conclusion, he told them to “go for it.”

It was “a monumental experience,” Nash says, perhaps “the greatest criminal trial in American history,” and the longest up to that point. He remembers that they picked up the case in the summer of 1981, pretrial motions were argued that October, jury selection began in November, Buono was sentenced in January 1984, and he and Boren worked on the case pretty much every day in between.

The trial featured “every kind of evidence,” Nash says, including critical forensics, such as fibers found on the victims that matched those found in Buono’s home.

He characterizes it as being “like 12 murder trials in one.”

While Bianchi “did everything possible to torpedo the case,” he says, much of his testimony could be corroborated. What the case essentially boiled down to, he posits, is that the crimes fit a pattern, there were certainly two perpetrators, there was “no question Bianchi was one of them,” and the other “couldn’t have been anybody but Angelo Buono.”

He had accumulated a good deal of vacation time, and decided to take a few months off after the sentencing. He and Clemens agreed to marry, and she has “put up with me for all these years,” he says with a laugh.

While the trial was a success, it also left him in the middle of a sticky political situation.

The trial had run straight through the 1982 general election, in which Deukmejian was elected governor and Van de Kamp as attorney general, which put him back in charge of the case. To his credit, Nash says, Van de Kamp gave the prosecutors everything they needed to bring the case to a successful conclusion.

But the winning of a case Van de Kamp had declared unwinnable created real difficulties, which dogged his bid for the Democratic nomination for governor in 1990. And since Boren couldn’t talk about the case—Deukmejian appointed him to the Newhall Municipal Court not long after the sentencing—the media came to Nash.

Van de Kamp, he says, tried to put the best face on the situation by claiming the new prosecutors “had better evidence than we had.” But “frankly, I didn’t agree with that,” Nash comments, and it became clear to him that his career in the office “wasn’t going anywhere.”

Philibosian Gives Advice

So he sought advice from a number of people, including Robert Philibosian, who had overseen the “Strangler” case as Deukmejian’s chief assistant before being appointed by Los Angeles County supervisors to replace Van de Kamp as district attorney. Philibosian urged him to apply for the bench.

“It didn’t hurt that George Deukmejian was governor,” he says, and he was named to the Los Angeles Municipal Court.

He started at what is now Metropolitan Court, then was assigned—along with Sandy Kriegler, now a justice of the Court of Appeal, and Harold Crowder, who retired in 1996 and died in 2009—to the then-new Hollywood branch of the court. The branch was created in response to residents’ pleas to county supervisors to attack prostitution, then rampant in the area.

“They found three tough judges, and we worked hard,” Nash says. “I was filled with piss and vinegar.”

His aggressive style led to complaints from defense lawyers.

But “the community at large loved the fact we were cleaning up Hollywood,” he notes.

Draws Election Challenge

In 1988, though, he was the only judge of the Los Angeles court to draw an election challenge, which came from a former deputy public defender, Enda Thomas Brennan. The Los Angeles County Bar Association rated Nash “not qualified”—his opponent was said to be “qualified”—and questioned his judicial temperament.

Philibosian resigned from LACBA in response to that rating, publicly denouncing the evaluation committee as “high priests and priestesses meeting in secret to wrongly label a highly qualified judge as unqualified.”

|

|

|

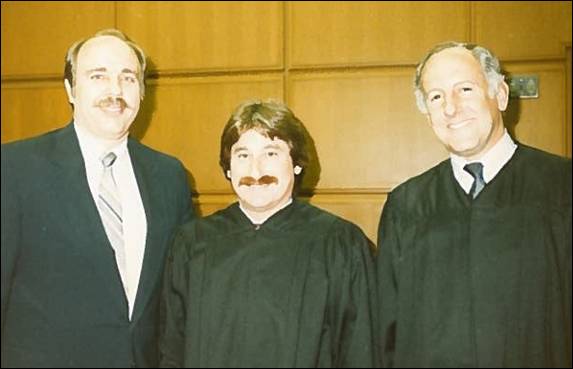

Nash at his swearing-in to the Los Angeles Municipal Court. At left is Roger Boren, now presiding Court of Appeal justice for this district’s Div. Two. At right is Ronald George, later chief justice of California and now retired. |

Nash says that “to this day,” he disagrees with the rating, but admits he “had some weaknesses,” including being “combative with the lawyers.”

He took the challenge seriously, he says, hiring the dean of judicial campaign consultants, Joe Cerrell, since deceased.

Despite the bar rating, he received a great many endorsements, including those of the Los Angeles Times and the MetNews. And he wound up with 61 percent of the vote.

“I took my lumps,” he says, in retrospect. But “I think I [became] a better judge because of it.”

Six months after the election, he requested and received a transfer to Van Nuys. He had no thought of seeking elevation to the Superior Court, he says, because he didn’t want to go through another evaluation process so soon after his LACBA experience.

Receives a Surprise

But he soon received a letter from the State Bar Commission on Judicial Nominees Evaluation, saying he was under consideration.

To this day, he says, he doesn’t know who submitted his name to the governor. But he went through the process, and says he was told by a JNE commissioner that he had turned around his critics.

And once again, Deukmejian gave him the nod. Happy for the elevation, he didn’t balk when he was assigned to dependency court, he says, even though “I didn’t know what it was.”

Once he got his feet on the ground, he reports, “I became a holy terror again.”

It was a place where “there was room for some passion,” and he found it a good fit for his talents.

“That system had so many things wrong with it,” he says. Unlike the criminal justice system, which “I sometimes felt had too much due process,” dependency court seemed to have none, he says.

“People said, ‘You went from being a conservative to a liberal,’ ” he recalls.

“Not really, but there were a lot of things that needed to be changed and I…pushed everybody involved,” he says. After a while, though “I sort of made the mistake of saying, ‘If they ever put me in charge of this place….’ ”

Leadership Positions

It was a classic case of “Be careful what you wish for,” he says. He wound up spending the next two decades as either supervising judge of dependency or presiding judge of juvenile court.

He was determined, he says, to do everything he could “to help these kids, who were unfortunate to be in the system in the first place.” And when he became juvenile presiding judge in 1997, he acknowledges, there was a good deal of trepidation within the system.

He realized, though, that he had to form a bond with the other stakeholders in order to get the results he wanted, he says. “I told everyone, my mantras are the three C’s—communication, cooperation, and collaboration.”

He expresses satisfaction with the end product, saying:

“I think we did some good work. I wish I could say that I fixed everything, but I can’t. But when I left, the system was better than I found it. And if you can say that, I guess you can say that your tenure was a successful one.”

After all, he says, given that 10 different presiding judges appointed him as supervising judge or presiding judge, “I guess I did something right.”

Among the many changes he is credited with over that period are creation of drug courts for both delinquency and dependency cases; development of psychotropic medication protocols for juvenile court youth; improved coordination between the dependency and delinquency courts; improvements in the quality of legal representation, and the creation of “Adoption Saturday”—court sessions in which more than 10,000 foster children have joined new families, and which became a national model.

Moving On

But after a period of public indecision, he announced in January 2014 that he would not serve beyond the year then left in his term.

“It was time,” he says. “The last few years have not been my favorites. The budget crisis took away resources from the juvenile court [and] from the court as a whole….

“You kind of know when it’s time to turn over the reins to someone else and to see what else life has to offer.”

So he left the court with “no particular plan” as to what he would do next.

He and his wife continued to indulge their passion for travel and live theater, and he started taking music and golf lessons and “doing things around the house,” before Levanas asked if he wanted to spend three days a week in delinquency court in Compton.

He claims he was really not interested when his successor first broached the subject, because he didn’t want to be, in effect, “a substitute teacher.” But he took the assignment, he says, in order to prove to himself “that I could still handle a calendar after all those years in administration.”

And he did, he says, remarking:

“I really loved it. I did some of my best work this last year.”

Call From Kuehl

He could have continued “indefinitely,” he says, had he not received a phone call from Supervisor Sheila Kuehl, saying she had the votes to appoint him to head the Office of Child Protection.

The creation of OCP was a critical part of the recommendations of the Blue Ribbon Commission on Child Protection, which was established in response to an internal report, leaked to the press, criticizing “systemic failures” that compromised children’s safety, linking such failures to a child’s preventable death.

“It will be a huge challenge,” Nash says, but “a unique opportunity…to help a lot of young people and their families.”

He admits to being “nervous…but also excited about the possibilities.” The opportunity to make a public impact “has always inspired me,” he says.

Nash comments that he understands that while the position has been described in the media as that of child protection “czar,” it is—as delineated by the board—far less powerful than the Blue Ribbon Commission proposed.

“Anybody who knows Los Angeles County…could figure out there’s no way that the Board of Supervisors would give that kind of authority to one individual [who] would become almost like a sixth supervisor,” he says.

What he hopes to do, he relates, is to build consensus decision-making like he did on the court, and as long as he has the board’s support, he says, “I think we can get things done.”

________________________________________________

Comments

As a Deputy Attorney General, Mike Nash, along with then Deputy Attorney General Roger Boren, courageously took on the prosecution of the Hillside Strangler, a case which the District Attorney’s Office had sought to dismiss. Mike and Roger used a combination of legal and trial skills, tenacity, creativity and sheer hard work to convict a devious cold-blooded killer who had terrorized the women of Los Angeles.

ROBERT H. PHILIBOSIAN

Of counsel,

Sheppard Mullin;

Former Los Angeles County district attorney

The long list of honors that Judge Michael Nash has received during his years as a Superior Court Judge are the professional honors of a man who has had an exemplary legal career. The fount for all of his recognized accomplishments is Judge Nash’s genuine concern for the human condition.

He often voiced dismay at the tragedy of the lives of people who are defendants in the criminal law system and this concern was magnified by his awareness of the plight of the children and families in the Juvenile Division of the Superior Court. His philosophy of caring about the welfare of people has been reflected in every nuance of his leadership. Hopefully, the great number of attorneys, who practiced in Dependency and Delinquency during the time that Judge Nash was at the helm of the Juvenile Division prior to becoming bench officers, will have internalized Judge Nash’s example of caring about children and their families.

It is his caring about the welfare of the children of Dependency Court which I always found to be remarkable. Judge Nash improved the welfare of the children by establishing Adoption Saturday, establishing juvenile drug courts, enhancing the communication between Dependency and Delinquency for “cross-over kids” and many other initiatives which have been adopted in Los Angeles County as well as outside of Los Angeles County.

Judge Nash’s caring about the children was especially evident to me when it came to his request to have clocks in the Courtrooms that reflected the fact that we were on “child time, not adult time” and what might be considered to be a “few months” to attorneys and judges, could feel like an eternity to a young child waiting to be returned to his or her family. Thus, one can see in each courtroom a clock with an image of a teddy bear on its face.

And, speaking of teddy bears, Michael Nash supported the Teddy Bear Program from its inception. Whether he enunciated this support in speeches, or allowed pictures to be taken of him holding a teddy bear during National Adoption Day media events or smoothed the way for the delivery of the bears to the Courthouse, his concern for the emotional state of the children was always evident.

In the Lobby of the Children’s Courthouse is a Display entitled, “Creating a Child-Friendly Courthouse.” That is what Judge Nash accomplished and will forever be a beacon of light for all those who follow in his footsteps.

L. ERNESTINE FIELDS

Attorney Founder and President, Comfort for Court Kids, Inc.

(2014 “Person of the Year”)

Mike Nash has the persona of a New York street kid, ready to go for the jugular as a former prosecutor. But, underneath that outer skin is a heart of gold with incredible tenderness and concern for children.

DAVID PASTERNAK

President, State Bar of California

(2014 “Person of the Year”)

I have enjoyed a special friendship with Judge Michael (“Mike”) Nash for over 50 years. From our days participating in the Fairfax High varsity football program to this very day. Judge Nash has always been a person of the highest integrity, passion, and commitment, no matter what he focuses on. That is exemplified by his performance when he was former Deputy State Attorney General in successfully prosecuting the defendants in the Hillside Strangler case after the local District Attorney’s office muffed it, his service as one of the three original judges in the former Hollywood Branch of the Los Angeles Superior Court, and his many years of dedicated service as the Presiding Judge of the Juvenile Justice Division of the Los Angeles Superior Court.

Throughout his legal career, he has been a completely dedicated public servant, pursuing the interests of justice no matter who the paities were, or what age they were. He brought a unique combination of legal acumen and compassion to his service as the Presiding Judge of the Juvenile Justice Division. Nothing gave him greater happiness than approving adoptions, thereby creating new families. But he also dealt with children who had either no permanent home and/or those whose misconduct was harmful to themselves and/or others, always following the law. but always with compassion where warranted. He always aimed at (and achieved) a just result. No doubt, these qualities are why he was chosen to be the Director of the newly created Los Angeles County Office of Child Protection. A more qualified individual could not have been picked for that position.

On a personal level. Judge Nash is a warm, loyal and caring friend. He has always had a dry. quick and somewhat sarcastic sense of humor. During our high school years, we enjoyed our close association through the Fairfax High football program. When I chose to spend a quarter at UC Santa Barbara, where Michael was attending, he took me under his wing, and introduced me to his fraternity brothers and roommates, several of whom have also remained my lifelong friends. We all transferred back to UCLA for our junior and senior years, celebrated our graduation from UCLA together and moved on to law school, and our legal careers. I have so many great memories of fun times we spent together, particularly dining our college years.

Throughout the ensuing years, we kept in touch, though somewhat sporadically. Nonetheless, whenever we saw each other, it was as if no tune whatsoever had passed. We simply picked up where we left off. That is the essence of a tine lifetime friendship. My wife, Trudi, and I offer our sincere congratulations to Judge Michael (“Mike”) Nash for his being selected as one of the 2015 “Persons of the Year.” It could not be bestowed upon a more worthy individual than my dear, lifetime friend.

STEVEN E. YOUNG

Attorney

Freeman | Freeman | Smiley

Judge Michael Nash was a credit to the bench and bar. He exemplified the qualities necessary to be an outstanding jurist. Intelligent, patient, well versed in the law and perhaps most importantly common sense. His demeanor was the perfect balance of professionalism while making those appearing before him comfortable. I am pleased to support this well-deserved honor.

ROBERT SHAPIRO

Criminal defense attorney

Glaser Weil Fink Jacobs Howard Avchen & Shapiro, LLP

Michael Nash is one of the most giving, supportive hard working jurists of our time. From law school to the bench and now as a layman, he gives so much to this community and the children in need. It is an honor to know Mike, and a privilege to call him a classmate and friend.

RICHARD M. HOEFFLIN

Attorney

Hoefflin • Burrows

Copyright 2016, Metropolitan News Company