Thursday, November 5, 2015

Page 7

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

License Plates With Low Numbers Became Political Rewards

By ROGER M. GRACE

Twenty-Third in a Series

Low license plate numbers initially were a status symbol because they connoted standing as a pioneering automobilist.

“[I]t is a well known fact that there are many automobiles in use which carry numbers that were assigned to other cars,” a columnist writes in the March 21, 1909 issue of the San Francisco Call. “The reason for this is that in many cases it is a piece of vanity on the part of the owner to exhibit a low number so that he may be considered by the general public a veteran.”

Of course, anything that is coveted, and is derived from official governmental action, is apt to be turned into a reward for political support. So it was that in the early part of the 20th Century, low license plate numbers became politicians’ “thank-yous,” signifying a favored status on the part of holders of such plates with the powers that be.

A patrolman was apt to think twice before ticketing a motorist whose vehicle bore such a plate.

![]()

Chris Matthews, in his 1988 book, “Hardball: How Politics Is Played, Told by One Who Knows the Game,” tells of a Democrat elected as Wisconsin’s governor in the “mid-1950s,” thanks largely to donations from a wealthy Republican.

The governor and a campaign aide met with the donor in the Executive Office on inauguration day, as Matthews tells it, and the benefactor was asked if there were “anything” he wanted.

“Well, there is one thing,” the man is quoted as saying.

The governor and the aide “braced themselves,” according to the author, and the donor asked:

“Do you think I could have one of those low-numbered license plates?”

Matthews continues:

“This is not an unusual story. Even the richest contributor is in a sense a political groupie. The low-numbered license plate symbolizes, after all, a connection with power….”

(Actually, such a meeting would have to have occurred in the late 1950s. The only Democrat elected as governor of Wisconsin in that decade was Gaylord A. Nelson, and that was in 1958; he took office in 1959.)

![]()

The initial license plate requirements in California were enacted, pursuant to statutory authorization, by local entities.

In Los Angeles, under a 1903 ordinance, the automobile number—to be issued by the city clerk—had to be “displayed on the rear of the automobile as nearly as possible in the middle thereof, so as to be at all times plainly visible” and the numbers had to be “not less than two and one-half inches high.”

The city did not supply the plates. Rather, it was up to the automobilist to create a display. Under the ordinance, the number could be painted “directly upon the automobile, if it be painted black…or shall be painted on a black sign or plaque of leather or iron or other material firmly affixed to the automobile.”

A Nov. 8 editorial in the Herald observes:

“No provision appears to be made for strangers wishing to visit Los Angeles by automobile conveyance. There is no wish, of course, to exclude such visitors, but it would be difficult to make an exception to the rule without jeopardizing the main purpose.”

![]()

|

|

State registration began in 1905. Political clout was, it would seem, a factor from the start in the state’s assignment of license plate numbers. The photo at right appears in the July 3, 1940 issue of the Sacramento Bee, bearing a caption which begins: “Bessie Mount is shown holding California’s first auto license plate.”

The caption notes that the plate, made of aluminum, belonged to John D. Spreckels, and that the Department of Motor Vehicles had obtained it from the man who had been his chauffeur in San Diego. It recites that the state’s “first five numbers were assigned to members of the Spreckels family.”

Speckles, who died in 1926, had reputedly been the wealthiest man in San Diego. He was a tycoon in the sugar business, owned the San Diego Union, and was influential in the state’s Republican Party.

![]()

In the years that followed, there was jockeying to obtain low-numbered plates.

Appearing in the Dec. 6, 1934 edition of the Oakland Tribune is this observation by columnist George Durno:

“It is the season for busy men to spend half their time trying to exert influence to the end they may get a license plate with a low number.”

A May 29, 1935 editorial in that newspaper remarks:

“We have had courtesy numbers and courtesy cards In California and holders of the same, for some reason which may not be mysterious, have held that they confer upon them a degree of license.”

![]()

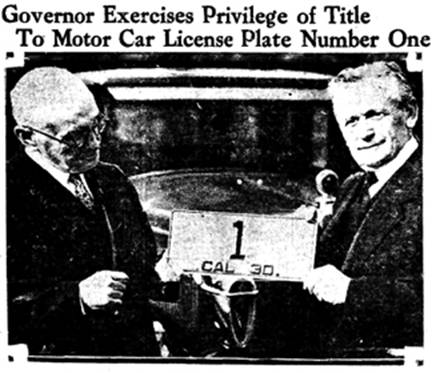

Political-officeholders not only dispensed low-numbered plates as rewards, but kept the ones with really low numbers for themselves. The following is from the Dec. 8, 1929 issue of the San Francisco Chronicle:

|

|

|

California motorists whose numerological hook-up predisposes them to the choice of the figure 1 are out of luck when it comes to picking up their license plate, because that numeral always goes to the Governor. The photo shows Frank G. Snook, chief of the State Division of Motor Vehicles, presenting Governor C. C. Young with 1930 plate. |

Young (on the right in the photo) was succeeded by Gov. James Rolph Jr.

A Dec. 30, 1930 Associated Press story relates:

“Governor-elect Rolph will have auto license plate ‘1,’ Governor Young will drive his car as former Governor with plate ‘1-X-1,’ and his daughter, Miss Barbara Young, is again to have her favorite, ‘1-Y-l.’

The nation’s leaders, also, had low-numbered plates. A Jan. 12, 1930 article in the San Diego Union provides this information:

“The President for his cars, has the numbers that begin at 100 and run to along about 110. Those are sacred white house numbers. Nobody lower than the President can get them at all.

“Number 111 is usually the reserved number for the vice president.”

The article goes on to say that numbers below 100 were reserved for the District of Columbia, with the lowest going to the three members of the Board of Commissioners, and others awarded to persons “influential with the district government.” (The district now has a mayor and a city council, but the preferential license plate scheme continues.)

There was, however, one block of nine numbers within the first 99 that was not controlled by the district, according to the Union: the chief justice of the United States had No. 50, and the associate justices were assigned numbers based on seniority, with the newest appointee receiving No. 58.

![]()

Rolph arranged for special license plates. An opinion piece in the Times on March 21, 1931, sizing up the governor, mentions:

“His friends don’t like to be stopped by traffic cops, so the Governor has ordered a special license plate for his friends’ automobiles with the letter ‘R’ on them—just so the cops can kinda go easy.”

A Dec. 16, 1932 United Press dispatch from Sacramento says:

“The ‘Royal R’ license plate series was in effect today at the personal request of Governor Rolph.

“The 500 automobile plates in the ‘R’ series, withheld for distribution to Rolph’s personal friends, were to have been distributed to the public, according to plans of Russell Bevans, registrar of motor vehicles, who said he had received no instructions from the governor’s office.

“Late yesterday Governor Rolph summoned Bevans to his office, and ordered him to hold out 500 plates to supply his friends for another year.”

An Oct 12, 1933 article in the Times advises:

“The royal family of Gov. Rolph’s special friends, as denoted by 1R license plates on their automobiles, is going to be increased to 1000 for 1934.”

![]()

Upon Rolph’s death on June 2, 1934, Lt. Gov. Frank Merriam became the state’s chief executive. He had no inclination to veer from the status quo with respect to license plates. A Nov. 2, 1935 article in the Berkeley Daily Gazette declares:

“California motorists who sport low-numbered license plates and would just as soon lose their cars as give up the low numbers probably will have nothing to fear from the present administration.”

Merriam is quoted as saying:

“It is not a question of favoritism. Many people have retained the same licenses year after year and have become closely attached to them, through sentiment. I believe the state can do no harm by providing a few little favors like this.”

This statement is attributed to Ray Ingels, director of the Motor Vehicles Department:

“Some people think that the holding of small license numbers is the result of political favoritism. It may have been in the past but now it’s just a matter of renewing the numbers from year to year and satisfying an overwhelming demand of people who hold those low numbers.”

The article notes that Ingels specified that allowing drivers to maintain their present license plates did not mean that the department would continue to “welcome requests for license numbers corresponding with street addresses or telephone numbers.” That sort of accommodation, he’s quoted as saying, entailed “the hiring of extra help and the digging into piles of licenses to pick out the requested numbers,” and often resulted in errors.

There was not, back then, a realization of a potential boon to the state in issuing “vanity” plates to those who would pay extra for them. On the other hand, there was not the existence of computers to guard against issuance of the same vanity plate to multiple motorists.

![]()

Next came Gov. Culbert Olson. This atypical governor—far, far to the left and an atheist—did make a sensible call in halting the low-number license-plate falderal.

A Jan. 5, 1939 AP account of Olson’s press conference that day in Sacramento says that the governor declared that while he regarded it as “a very small matter,” it had been determined “that as a matter of policy there will be no more preferential treatment of auto plate applicants.”

The Times, in a Jan. 24, 1939 editorial, pouts:

“Distribution of low-number auto license plates is, by Governor Olson’s order, on a ‘first-come, first-served’ basis, though only in San Francisco and Oakland, none being sent to Southern California.

“But who wants low-number plates on that basis? Heretofore their possessor was, or was thought to be, a person of some distinction or at least pull. Now the only thing possession of the plates proves is that somebody elbowed himself to the head of a line. Since low-number plates are more easily spotted by the cops they are a dubious advantage now.”

![]()

While Olson put an end to low-numbered license plates in California going to political boosters, that custom persisted elsewhere.

The Jan. 8, 1984 edition of the Boston Globe tells of practices of the man who four years later would become the Democratic Party nominee for president of the United States, Massachusetts Gov. Michael S. Dukakis, saying:

“Those who decried patronage in government paid scant attention when Dukakis abandoned the lottery system he had instituted for state summer jobs during his first term or when he began issuing low-number license plates to political supporters.”

A March 23, 1986 article in that newspaper again scores Dukakis, saying he “even resorted to issuing low-number license plates.”

However, the Globe on April 22, 1987—one week before the governor formally declared his candidacy for the Democratic presidential nod—carried a story which says Dukakis “announced the resignation of the registrar of motor vehicles, Alan A. Mackey,” and recites:

“Dukakis was reportedly furious when he learned that Mackey had handed out the coveted low number plates to friends and relatives and the friends of legislators in direct violation of a 1983 gubernatorial ban.”

The newspaper apparently forgot that, according to itself, it was Dukakis who had ended the ban in 1984.

Copyright 2015, Metropolitan News Company