Thursday, October 29, 2015

Page 7

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

Paper ‘Courtesy Cards’ Were Desirable—but Gold Ones Were All the More So

By ROGER M. GRACE

Twenty-First in a Series

“Courtesy” cards—police officers’ business cards with a message scribbled on them asking that “every courtesy” be extended to the bearer—were prized in the long-ago days when they were given out…but not so treasured as those of gold.

|

|

|

RAYMOND E. CATO |

Raymond E. Cato, chief of the California Highway Patrol, bestowed such cards in the 1930s.

A United Press dispatch of May 23, 1935 tells of remarks by Santa Ana Township Justice of the Peace Kenneth E. Morrison, in imposing a five-day jail sentence on a repeat speeder who flashed a courtesy card issued to him by Cato. Morrison, who later became an Orange Superior Court judge, is quoted as saying:

“I wonder how Chief Cato reconciles such a practice of giving his special friends unlimited right to violate the traffic laws and imperil the motoring public. I wonder who is paying the bill for these gold-plated cards. Is the highway patrol paying it at the expense of the taxpayers for Chief Cato’s special men, or is Cato paying the bill himself? If so, by what authority does he use the authority of the highway patrol?”

The answers were carried by UP the following day. A dispatch from Sacramento says the cards are “paid for, in most instances, by the persons receiving them, officers of the patrol said today.”

It continues:

“The plaques cost $4 each, unless the recipient prefers solid gold.

“When Cato first started the habit of issuing the cards, he paid for them himself, but found this an expensive practice, so began asking recipients to foot the bill.”

The dispatch mentions:

“Patrol officials here reiterated Cato’s statement that the cards were for identification purposes only and were not recognised in cases of law violation. Some 200 have been issued.”

“For identification purposes only”? The need for such means of identification is unclear…given that California had required drivers’ licenses since 1913.

![]()

The wire service followed up on the story the following day, providing this statement from Gov. Frank Merriam:

“I have no objection to the issuance of cards for courtesy and identification., but I do object to any special privileges in the matter of observing and obeying laws.”

The May 25 report says:

“The cards are metallic, gold-plated. On the face is engraved: ‘The California Highway Patrol extends courtesies to _______.’ Cato’s signature appears underneath. Accompanying issuance of the plaques is a form letter which reads:

“I am enclosing a courtesy plaque. This may be used as a means of identification in cases of emergency, [b]ut is not intended to excuse wilful or reckless violations of the law. I trust you will find its possession a pleasure to you and a service in the case of emergency.”

If it does not shield the bearer from consequences of “wilful” or “reckless” transgressions, by necessary implication it will immunize the bearer from consequences of negligent breaches of the law.

![]()

The reaction of newspapers to Cato’s practice was decidedly negative.

For example, a May 27 editorial in the Riverside Daily Press opines:

“Californians have learned with amused, if not serious interest, that E. Raymond Cato, chief of the California highway patrol, issues gold courtesy cards to distinguished personages and to some personal friends. The implication, as the holders view the matter, is that to exhibit the card when signaled down by a traffic officer will bring immunity.”

It says, facetiously:

“[Cato’s] friend in Orange county did a most ungracious thing when he indicated the card could ‘fix’ a speeding charge. There is no such representation. Of course not!

“For those who will be putting in applications for courtesy cards, Mr. Cato’s office is at Sacramento.”

An editorial in the Oakland Tribune on May 29 comments:

“Most Californians hope that the patrol always extends courtesies, but most drivers may reason…that liberty to break laws is included among the gifts bestowed with a golden card.”

It recites that Morrison ordered the jailing of a man who had flashed such a badge, and comments:

“Had he done otherwise, it is probable that one-half of the State, reasoning they could be called special friends to the administration or ‘distinguished personages’ would have applied at once for the magic tickets.”

![]()

No more gold cards were to be distributed, under an edict of Cato’s boss, R. Ray Ingels, director of the Department of Motor Vehicles. An Aug. 8 United Press dispatch from Sacramento says that on the heels of Ingel’s action, Merriam issued this directive for Ingels to pass on to CHP officers:

“All courtesy cards, gold or otherwise, with the exception of those issued to the authorized representatives of the press, and all replicas, imitations or miniatures of the official Highway Patrolman’s badge, shall be immediately confiscated when presented to you as a reason for avoidance of a citation for any infraction of the Motor Vehicle Laws of the State of California, and forwarded to the Sacramento office of the Department of Motor Vehicles.”

An Aug. 11 editorial in the Times applauds those steps, saying:

“The invalidation of ‘courtesy cards,’ miniature badges or other special favors to certain private pleasure drivers is a move in the right direction. There is no reason for a privileged class of motorists save those engaged in essential public services….

“Apart from the consideration of fairness, there always has been the danger of the cards falling into the hands of criminals enabled by their use to escape apprehension by the highway patrols.

“Courtesy cards have been abused even by their rightful holders; in fact they are an invitation to abuse. The main objection, however, is that all who contribute to the maintenance of the highways are entitled to equal privileges and to no more.”

An editorial in the Aug. 14 edition of Yolo County’s Woodland Daily Democrat declares:

“Mr. Ingels recent ruling Chief Raymond Cato must stop the practice of issuing gold courtesy cards and miniature privilege badges was most sensible and timely.

“Just why political pets of any administration should be privileged to travel faster than any one else on the highway or subject the public to more hazards than any other car owner was always unexplainable. There was no excuse for these special courtesy cards.

“Ignoring traffic officers and regulations, by flashing gold certificates and badges, got to be a habit. The holders of the cards could give the traffic officers the good old-fashioned horse laugh and get away with it. But now it is to be different.”

![]()

But, there were relapses. Five CHP officers were “suspended or reprimanded,” a Sept. 4, 1961 Associated Press dispatch says, based on frolics with young women—dubbed within the department as “Coffee Date Kids”—whom the officers had met through traffic stops. One of the women, an inspector is quoted as saying, carried a courtesy card to protect her against receiving traffic tickets.

That card, however, was undoubtedly not gold-plated.

The CHP, in recent years, was linked to the bestowing of special license plate holders on contributors to a foundation, with those plates supposedly warding off tickets…to be discussed in a later column.

Cato was not the only law enforcement officer to award gold cards. Sheriff Eugene Biscailuz gave out an untold number of honorary sheriff badges, but was not known for bestowing gold cards. He did hand one to the president of Mexico, according to a March 5, 1935 Times report.

![]()

Politicians also handed out gold courtesy cards. In some instances, they were akin to a key to the city; by virtue of the status of the recipients, the cards were not apt to be misused. However, they also went to persons who might well flash them in expectation of special treatment.

One person who would fit in the former category was President Benjamin Harrison. The May 7, 1891 issue of the Daily Alta California tells of the actions of San Francisco Mayor George H. Sanderson in connection with his visit:

“[S]hortly before the President’s arrival the Board of Supervisors, at a regular meeting, adopted a resolution tendering the Chief Magistrate the freedom of the city. This resolution was, in the due course of business, presented to the Mayor and duly signed. It is stated that about this same time Mayor Sanderson visited the jewelry establishment of George C. Shreve & Co. and bargained for a gold card about 3x5½ inches in size, to be engraved with wording to the effect that ‘by resolution of the Board of Supervisors the freedom of the city is hereby tendered to Benjamin Harrison, President of the United States.’ This was signed, ‘George H. Sanderson, Mayor.’ The names of the Supervisors, as well as the Clerk of the Board, were all studiously omitted, probably for the reason that they ‘don’t hold office high enough to be on the same card with the Mayor.’ This golden card was duly presented to President Harrison by Mayor Sanderson at the ferry on the night of the President’s arrival.”

The recitation of a presentation that had occurred on April 25 appears in the May 7 edition because of a more recent development: the board received a bill from the jeweler for $185 ($4,510 in terms of today’s dollar), and the reaction was that the mayor could pay for his gift out of his own pocket.

Despite the monetary value of the card, it was apparently a ho-hum offering, so far as Harrison was concerned. The April 26 issue of the San Francisco Call notes that “without glancing at it the president thrust it into one of the capacious and ever-ready pockets of his overcoat.”

![]()

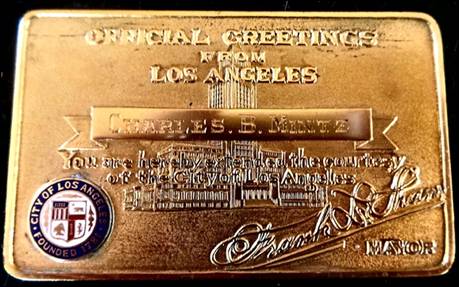

Here’s a gold card which Los Angeles Mayor Frank Shaw—whom voters were to recall from office in 1938—gave to motion picture producer Charles B. Mintz (the man who stole the Oswald the Rabbit character from fledgling cartoonist Walt Disney):

|

|

The card is in the collection of Keith Bushey, a retired commander in the Los Angeles Police Department and former deputy chief of the San Bernardino County Sheriff’s Department, mentioned here before. The depiction is not of admirable clarity; I took a shot of it with my pocket camera when I recently had the privilege of viewing Bushey’s $2 million collection of badges and other law enforcement memorabilia.

An April 2, 1936 article in the issue of the Times tells of such a card being presented by Shaw to the president-elect of Cuba. An Oct. 26 piece that year in the same newspaper reports a like gift to songwriter Carrie Jacobs Bond, noting:

“Mrs. Bond, who recently celebrated her seventy-fourth birthday, has been a resident of Los Angeles for many years and plans a trip to Chicago shortly, hence the courtesy card.”

![]()

“Gold” cards have, in recent years, been made not of gold, but plastic. There have been the American Express “gold card,” “gold cards” offered by banks, stores, and campuses, and those awarded to seniors.

The plastic gold card of recent vintage most closely resembling, in purpose, the gold-plated cards provided by Cato was the “City of Los Angeles Parking Violations Bureau” gold card, given out to friends by the Mayor’s Office and members of the City Council. On the back of the card, there was an assurance to the holder that if he or she had an “urgent need to resolve any parking citation matter which requires special attention,” telephoning 213-688-2701 would result in being “immediately connected to our Gold Card Specialist.”

The “Gold Card Services Desk” had been in operation for about 20 years when it came to an end, rapidly, in the aftermath of a 2011 report by then-City Controller Wendy Greuel pointing to the existence of the desk, and commenting:

“You should not need political pull to expedite the investigation of a ticket.”

Copyright 2015, Metropolitan News Company