Thursday, September 24, 2015

Page 7

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

Carrying a Badge, Elvis Presley Play-Acts the Role of a Policeman

By ROGER M. GRACE

Fifteenth in a Series

There have been countless Elvis Presley impersonators, as we all know. What is not generally known is that Presley was himself an impersonator, occasionally assuming the fictional role of a peace officer, possibly believing he actually was one.

Public officials who catered to him—including President Richard Nixon—provided Presley with a faint basis for that belief, including supplying him with badges and other law enforcement credentials. However, any belief on Presley’s part as to having powers of detention and so forth, if he truly did harbor such a belief, was objectively unreasonable.

But did this iconic performer in glittery garb, denominated in the press as a “king,” dwell in a land of reality? Or was he a monarch in Never-Never Land, oblivious—through effects of drugs, or ego, or naiveté—to the falsity of powers seemingly bestowed on him?

![]()

As a youngster, Presley wanted to grow up to be a policeman, according to press accounts in the 1970s. He collected badges. If he performed in a city, he’d want a badge from there.

What he wanted was not merely an honorary badge, but a real one. And he obtained several, some with his name or initials inscribed on them.

Columns in this series have pointed to the prospect for mischief where officials conferred honorary badges on persons outside of law enforcement, badges which merely resembled real ones. Here is the saga of genuine police, sheriff, and trooper badges and other credentials being supplied to an explosive individual, outside the ranks of law enforcement, who would on multiple occasions shoot a gun at a TV set to remove the image of rival singer Robert Goulet, or blast at a chandelier, a hotel ceiling, or his daughter’s swing set.

There are no known incidents where Presley attempted to make an arrest. But, as will be seen in recitations in columns to follow, he did flag down a jet on a runway, flashing a federal badge, and sometimes pulled over motorists in Memphis, pursuant to his officially issued but worthless ID, lecturing them on their driving habits. He had a rotating blue light atop his car, as well as a siren. He possessed a “black flashlight,” a night stick, and handcuffs.

![]()

While male rock ’n’ roll performers of his day wished they were Presley, and swooning females wished they were with Presley, the gyrating exhibitionist, himself, apparently wished that he were Joe Friday, and seemingly fantasized that he was.

Presley, who thrived on publicity, did not covet it in connection with his accumulation of badges, the bulk of which were no doubt bestowed on him unlawfully. In fact, he insisted on secrecy—even in connection with his meeting with Nixon in the Oval Office in which he sought a federal narcotics badge. In light of the absence of contemporaneous news coverage of the presentations, it’s no wonder that uncertainties exist, in many instances, surround the gifts of badges.

Below is information on badges Presley received in one city.

THE DENVER POLICE DEPARTMENT in 1970 was enthralled to receive from Presley $5,500 to outfit a gym for police officers. In return, the chief of police, George L. Seaton, on Nov. 17, 1970, presented Presley with a badge. The son of the now-deceased police chief, in a 2004 entry on his blog, recounts that it was an honorary lieutenant’s badge.

|

|

|

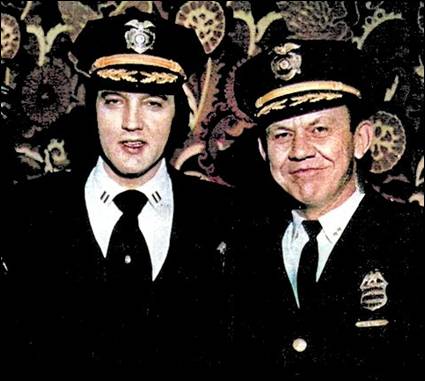

Denver Police Department Presley, in uniform, is seen with Denver Police Chief Art Dill. |

For Presley, that was not good enough.

A July 15, 2012 article on the Denver Post blog says:

“Art Dill, who succeeded Seaton in 1972, formed an even closer relationship with Presley, later giving The King a badge and a captain’s uniform.”

It was an actual captain’s uniform (with the official metal insignia on the cap) and an actual captain’s badge.

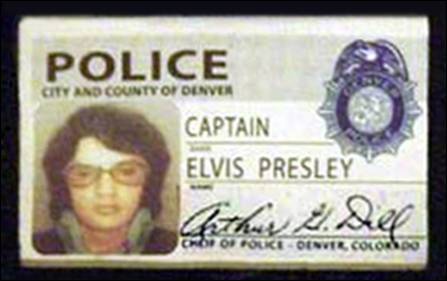

An identification card bears Presley’s name and likeness with the word “CAPTAIN,” without the word “Honorary.” See for yourself:

|

|

|

Presley’s Denver Police Department ID card. |

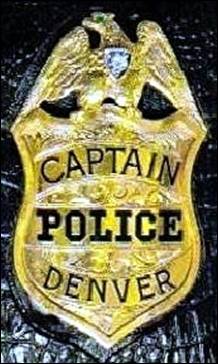

A Sept. 9, 2004 article in the Denver post, reporting on Dill’s death, recounts that the badge was presented to Presley in 1976 and that “Presley offered to buy Dill a car, but Dill demurred.”

Other members of the department did not shun Presley’s largesse. A March 10, 2003 report in the Rocky Mountain News on efforts to bar moonlighting by police officers recites that in 1976, “Elvis Presley bought automobiles—two Lincolns and two Cadillacs—for three Denver police officers” who “became friends with Presley when they worked off-duty security at his Denver concerts.” Oh, and Dill did accept from Presley a World War I Colt .45 pistol.

In Alanna Nash’s 1995 book, “Elvis Aaron Presley: Revelations From the Memphis Mafia,” the singer’s personal aide, Marty Lacker, is quoted as saying that Presley would put on the uniform “and parade around, just to show he had it.”

An article carried nationally on May 27, 1982, by newspapers subscribing to the Los Angeles Times-Washington Post Syndicate says that Presley wore the uniform “to two police social functions and asked to go along, in uniform, on a real drug bust.”

The article says that there was “conflicting testimony” at a Colorado state Senate hearing “as to whether this request was granted.”

|

|

The Aug. 12-18, 1999 edition of the Memphis Flyer says the Denver captain’s badge was almost among the items auctioned off. It quotes Greg Howell, manager of exhibitions and collections for Graceland (Presley’s home in Nashville, now a museum), as relating:

“The more I looked at it, I said, oh, we can’t get rid of it.”

It was appraised and, Howell says, the inset gem “was a very high-quality diamond.”

![]()

What has been overlooked is that although Presley was provided with a badge and ID card that were both authentic, he was not lawfully appointed by Dill as a captain, or to any post.

“Employment with the police department of the City and County of Denver is governed by the city charter,” a Nov. 14, 1972 Colorado Court of Appeals points out.

It notes that under the charter, the Civil Service Commission “shall provide for promotion in the classified service on the basis of ascertained merit and seniority in service and standing upon examinations, and shall provide, in all cases, that vacancies shall be filled by promotion.”

Presley could not have been promoted from lieutenant to captain because he was only an honorary lieutenant.

The charter section continues:

“All examinations for promotion shall be competitive among such members of each department as desire to submit themselves to examination.”

Presley didn’t take a competitive exam.

And there were a few other hitches, such as Presley not having gone through the police academy.

An irony is that if Presley’s supposed commission as a captain had been valid, it would have put a bit of a crimp in his career and a singer and actor. He would have been precluded by a charter provision from having “other employment.”

![]()

There is also the overlooked matter of illegality on the part of Presley and Dill.

A Denver Municipal Code section, which has been in effect since 1950, provides: “Uniforms and badges specified and adopted by the manager of safety shall be worn only by members of the police department while in active service.” So, Presley broke the law whenever he wore the uniform and badge.

The next paragraph declares: “No badge shall be given to any person other than a member of the police department.” Thus, the police chief, too, acted unlawfully.

Other Municipal Code sections also come into play.

Theoretically, Presley and Dill could have been jailed and fined for their violations of the ordinances. But who would undertake to arrest the chief of police? And who would arrest an international celebrity whose violation of the law was personally facilitated by the chief? There was a de facto immunity from prosecution.

Presley’s supposed law enforcement status is generally alluded to light-heartedly. Yet, is there not an element of outrageousness here? The bestowing of honorary badges, which was occurring then across the nation, was bad enough, leading as it did to recipients gaining benefits from those in whose faces the faux badges were waived, assuming them to be real. Dill, in providing to someone who was not a law enforcement officer an actual badge, along with credentials and a uniform, went beyond the custom of the day.

Yet, he was not alone in so accommodating the “king.” In localities across the nation, Presley was not modest in his requests, and heads and members of law enforcement agencies were all too eager to do his bidding.

![]()

![]()

![]()

TRUE NAME: In case you’re wondering about the final upshot in Miami wealth advisor Patrick J. Dwyer’s effort to litigate anonymously in the Los Angeles Superior Court as “John Doe,” Judge Michael P. Linfield ripped the mask from his face, re-titling John Doe v. Financial Industry Regulatory Authority, Inc. as “Patrick J. Dwyer v. Financial Industry Regulatory Authority, Inc.”

As recounted here in June, Dwyer sued to have the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority, Inc. (“FINRA”) ordered to pull seven customer complaints about him from its online database.

Linfield, in a ruling signed June 30 but not immediately made available, denied relief. He found that while Dwyer had asserted that the complaints were baseless, he failed to prove it.

Still remaining was an eleventh-hour motion by FINRA to have Dwyer’s name bared in the caption.

Doe’s identity had been revealed here in two columns, as well as on the “Financial Advisor IQ” website which utilized information from the columns.

“Mr. Dwyer’s name is now in the public forum,” FINRA’s lawyer said, in moving for an order amending the caption. Linfield agreed.

In another secrecy case…

In July, I noted that Div. Two of the Fourth District Court of Appeal, in an opinion by Presiding Justice Manuel A. Ramirez, proclaimed that “a motion to seal declaration in support of the petition for writ of mandate” was granted. That was not playing by the rules. Under NBC Subsidiary v. Superior Court (1999) 20 Cal. 4th 1178 (and court rules pursuant to that decision), specified findings must be made before a document is sealed, and no such findings had been made. Ramirez could not remedy this; the opinion had been made “final forthwith.”

This newspaper made a request to the Supreme Court to grant review, on its own motion, and remand the matter for reconsideration in light of NBC Subsidiary. It didn’t. Apparently the high court members don’t mind if their decisions are disregarded by members of lower courts.

Copyright 2015, Metropolitan News Company