Thursday, August 13, 2015

Page 7

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

Controversies Over Badges Erupt at State Level

By ROGER M. GRACE

Thirteenth in a Series

Most controversies in California over honorary badges have taken place at the city and county levels. There have been a few tempests at the state level...to wit:

California legislators formerly gave out honorary badges.

An Oct. 2, 1977 article in the Long Beach Independent Press Telegram quotes a Long Beach deputy city attorney, David Schacter, as saying that the badges “look like state police badges,” commenting:

“[I]f ever I saw a misuse of a badge, that’s a misuse.”

The article says that Schacter (who later became a Los Angeles Superior Court judge, and is now deceased) told of posing as a customer in a nightclub owned by a man who, with other investors, was seeking a permit to open such an establishment in Long Beach. The man boasted of how much clout he had, brandishing a gold Assembly badge to prove it.

Schacter is quoted as saying that a Los Angeles attorney (whom he wouldn’t name) would show off a similar badge and “brag about how it would get him out of tickets.”

![]()

The practice of dispensing such badges came to a halt in the aftermath of the prosecution in Los Angeles Superior Court of one Pirikana L. Johnson, a felon who was on probation, having pled guilty in U.S. District Court for the Central District of California to offenses involving identity theft.

Upon being questioned by police at the Redondo Beach Pier in the early morning hours on Feb. 18 and March 18, 2006—on each occasion after he emerged from a nightclub—Johnson flashed a badge, bearing the Assembly seal, which indicated that he was a “California State Assembly Commissioner,” a nonexistent office.

The first police encounter with Johnson at the pier merely entailed a noise offense: music on his car radio blaring loudly. On the latter occasion, Johnson was arrested for driving while intoxicated and driving without a license.

Then, on Dec. 4, he was arrested on charges related to use of the badge, including impersonating a state official.

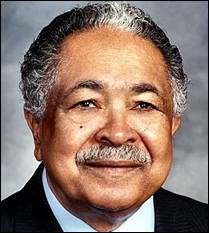

It emerged that his phony badge was a gift from the office of then-Assemblyman Mervyn Dymally, D-Compton (now deceased). Dymally denied ever personally bestowing a badge.

|

|

|

MERVYN DYMALLY |

Eighty such badges had been purchased from a private badge-maker in Los Angeles. A Dec. 5 article in the Times notes:

“Four men speaking on condition of anonymity showed a Times reporter Assembly commissioner badges that they said they had received after paying several hundred dollars apiece in what they believed were campaign contributions intended for the assemblyman. But they said they did not make the payments directly to Dymally, nor do their names appear as contributors on his campaign finance reports.”

![]()

Dymally, an African American, protested that the arrest of Johnson for falsely identifying himself—and news accounts pointing to him as donor of the badge—were “racist.”

A Sacramento Bee article on Dec. 14 quotes the 81-year-old Dymally as saying:

“It’s nice and proper and polite to say that racism doesn’t exist in American society and politics. But it exists. People have to deal with that. Why am I being singled out?”

Dymally, apparently an adherent to the adage that the best defense is a good offense, became offensive. His approach proved ineffective.

•A Dec. 16, 2006 editorial in the San Diego Union-Tribune scoffs:

“…Assemblyman Mervyn Dymally’s habit of giving official-looking badges to supporters—which came to light when a backer of the Compton Democrat allegedly impersonated a state official—is a terrible idea. Assembly Speaker Fabian Núńez, D-Los Angeles, was right to ask Assembly Rules Committee Chairman Hector De La Torre, D-South Gate, to investigate.

“Unfortunately, Dymally has chosen to make matters much worse for himself by insisting that the criticism he is facing is racist—and that De La Torre is ‘the most racist legislator I have encountered in over 40 years.’

“This is both graceless and ridiculous, as Dymally, a former lieutenant governor and congressman, knows full well. He should stop handing out badges and stop pretending he’s the victim of a racist witch hunt—immediately.”

•A tongue-in-cheek editorial in the Los Angeles Times, appearing on Jan. 22, 2007, asks:

“WHAT’S THE POINT of contributing money to a winning candidate if you can’t get anything in return—such as, say, an official badge to wave at the cops when they pull you over?”

It continues:

“Speaker Fabian Nunez (D-Los Angeles) has issued an order banning distribution of official California State Assembly Commissioner badges simply because of an unfortunate incident last year, in which a man confronted by Redondo Beach police allegedly flashed a badge issued by Assemblyman Mervin Dymally (D-Compton) and announced, ‘You don’t know who I am.’ Such statements—‘Do you know who I am?’ would also have been acceptable—go hand in hand with badge privileges. Or they used to. Now Nunez’s ban places this august tradition in jeopardy.

“Dymally, at least, handled the situation with typical aplomb. Asked about the dozen or so badges his office distributed, he explained that having one is not illegal. ‘If it is,’ he said, ‘arrest everybody. Arrest some white people too.’ Dymally has retrieved the badges after having been notified by the Los Angeles County district attorney’s office that distributing them was, indeed, illegal.”

![]()

Johnson was convicted by a jury on all charges. An Aug. 14, 2007 Times article, reporting on the verdict, notes:

“The Los Angeles district attorney’s office investigated Dymally but declined to prosecute after his attorney collected about 40 of the badges.”

An Aug. 29 Times article says Johnson was sentenced to a year in jail, plus fines and penalties amounting to about $5,600.

And what has Johnson been up to lately? He was the defendant in an action brought by the Los Angeles County Child Support Services Department to establish his paternity of a child who is receiving welfare and to force him to meet his parental obligations. A notice of entry of default judgment against him was filed April 30.

The Office of Attorney General on July 30, 2007 promulgated a formal opinion (discussed here previously) advising that the gift by a sheriff (or, by necessary implication any other public official) “of an honorary badge to a private citizen violates California law if…the badge falsely purports to be authorized, or would deceive an ordinary reasonable person into believing that it is authorized, for use by a peace officer.”

Somebody in the office was savvy enough to realize that it would be a good idea to round up the slew of such badges disseminated (before Brown became AG) to deputies attorney general.

A Daily News editorial of Sept. 5, 2007 says:

“We hope the practice of handing out badges to every political hack who wants one is on the wane.

“State Attorney General Jerry Brown has announced the recall of 1,200—1,200!—honorary badges to staff attorneys in Los Angeles and around the state to avoid continued misuse of them. It’s a wise move; no one who isn’t a sworn law enforcement officer or agent should be allowed to carry a badge.”

Handing out courtesy badges that looked like the real ones to members of the general public—donors and pals and family members—was not merely “on the wane,” following the AG opinion, but virtually ceased. Though statutory law had been clear before then, public officials now suddenly grasped that they could be criminally liable for making gifts of badges that appeared to be, except on close examination, authentic.

What did not stop was the supplying of badges to public officials who were not in law enforcement. The Daily News editorial notes that “the badge pipeline has been turned off for legislators” by virtue of Nunez’s order, but that “plenty more nonsworn workers in California still have access to them, including city council members, county supervisors, dispatchers, dogcatchers and even courtroom clerks.” Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department badges for officials in cities served by that department were recalled following a flap previously recounted here, but it remains that various public officials at the state and local levels do, personally, continue to carry badges, notwithstanding a lack of law enforcement status.

|

|

|

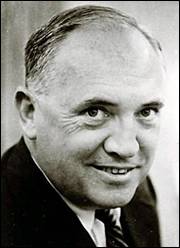

CHARLES A. O’BRIEN |

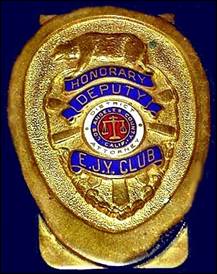

A candidate for statewide office made the matter of badges a major issue in his campaign. In 1970, Chief Deputy Attorney General Charles A. O’Brien, a Democrat, was locked in a run-off battle with the Republican nominee for state attorney general, Los Angeles County District Attorney Evelle J. Younger. O’Brien laced into Younger for designating contributors of $250 or more to his office-holder account as members of the “E.J.Y. Club” and providing them with either cuff links or a money clip in the form of a badge.

A recitation of that and other allegations by O’Brien appear in a “Perspectives” column of Oct. 15, 2008 (in a series on past Los Angeles County DAs) at http://www.metnews.com/articles/2008/perspectives101508.htm.

O’Brien’s charges were typically adamant and unsubstantiated.

(I remember interviewing O’Brien in 1970 by telephone and asking him to respond to criticisms that he was conducting a mudslinging campaign. I held the receiver inches from my ear as he shouted his heated response.)

An Oct. 14 O’Brien campaign ad in the San Diego Union and, I would suspect, other newspapers, contains a depiction of the money-clip and cuff links and says:

How can we expect people to respect the law when they see and hear about things like this.

Sometimes there are valid reasons why an unauthorized person should receive an honorary title badge and preferential considerations.

But these cases are far and few between.

In this case, all you needed to get this badge was an ego that needed inflating and some money.

Badges sold for $250.00 each.

Plus, it was necessary to have a ‘contact’ or friendship with EVELLE YOUNGER, Los Angeles District Attorney.

That’s all. With these simple requirements you could get a badge, flaunt the law, or make light of it. Whatever.

The money clip, if fastened to a flap in a wallet, would, indeed, look like a badge…but not an actual law enforcement badge. It’s too small. The length, top to bottom, is about that of an AA battery. The possibility that anyone actually got out of a traffic ticket by flashing such an “E.J.Y. Club” money clip seems unlikely.

And is it conceivable that some motorist avoided a citation by waiving cuff links in front of an officer?

|

|

From a legal standpoint, the conferring of the money clips and cuff links did not violate the law. The 2007 AG opinion points out:

“[I]f the badge, when viewed in isolation, is of a shape and design that could not reasonably be mistaken for an authentic peace officer badge, the sheriff [or other public official] would not run afoul of [Penal Code] section 538d, even if the recipient later were to display the badge for an improper purpose and did so in such a way, i.e., quickly and with an assertion of authority, that would deceive a member of the public into believing that the badge was authentic.”

![]()

![]()

![]()

POST SCRIPT: There was a similar instance 38 years earlier of a candidate awarding badges to backers. But these mementos, too, were too small to be confused with actual ones.

The candidate was Los Angeles City Prosecutor Charles P. Johnson, an opponent of a recently appointed Los Angeles Superior Court judge, Isaac Pacht.

A Sept. 21, 1932, Times story provides this description:

“The badge itself is a neat gold affair, about half the size of the familiar police badge. Under the proud sheltering wings of an American eagle, engraved and embossed in blue enamel on a natty golden scroll, appears the name of the fortunate holder. Directly below the holder’s name is an embossed wheel with ‘City Prosecutor, Los Angeles,’ circling the city’s shield on a field of white enamel set off by gold, red and blue embossing.

“And at the base is the blue-enamel title: ‘Investigator.’ ”

Pacht prevailed in the county’s Nov. 8 general election. Voters in the City of L.A., on that date, approved a charter amendment merging the Office of City Prosecutor into the Office of City Attorney, resulting in Johnson being without a job the following year after the Legislature ratified the change.

Pacht (1890–1987) was the father of Jerry Pacht (1922–1997), who also became a Los Angeles Superior Court judge.

Copyright 2015, Metropolitan News Company