Monday, July 20, 2015

Page 6

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

Propagators of the Jury System: the Vikings, a King, and a Pope

By ROGER M. GRACE

U.S. Supreme Court opinions, and other sources, have perpetuated the myth—as academicians have concluded it to be—that the right to trial by jury is traceable to the Magna Carta. A USC professor of law and history, Dan Klerman, has been quoted here, from his “Law Week” remarks, as explaining that the Magna Carta merely ensured that judgment would not be passed on barons other than by other barons.

But if Magna Carta is not the source of the English jury system, how did this institution —which was to be transplanted to the British colonies in the New World and perpetuated in the states following independence—come into existence?

Historians have groped with, and debated, that question for centuries.

![]()

Give some credit to the “Northmen”—the Scandinavians from Norway and Denmark who migrated south. Being of Norwegian extraction, I’m all for giving credit to Scandinavians.

Now, you just might have a distorted image of my distant ancestors as naught but a seafaring band of pillagers and rapists. The Vikings were, indeed, brutal, but in brutal times. Note what Frank R. Donovan says in his book, “The Vikings,” which went into print earlier this year:

“Although the period from the end of the eighth century to the middle of the eleventh is called the Viking Era, all of the Northmen who sailed from their homelands during that time were not Vikings. The true Viking was a sea-roving adventurer. Such a man was said to go i viking….

“While raiding parties are seen as the norm, many of the Northmen of the Viking Era were not invaders and never went i viking. Contrary to sword-swinging popular imagery, some came to new lands as traders and stayed as settlers—there were Norwegian encampments in the Orkney and Shetland islands by the beginning of the ninth century. Some went exploring across the North Atlantic; others [the Swedes] opened trade routes across Russia to Constantinople. Some even served as mercenaries and fought other invading Norsemen. Indeed, the Northmen who went voyaging after the second half of the ninth century generally had a more serious purpose than hit-and-run raiding. But history labels them all Vikings.”

![]()

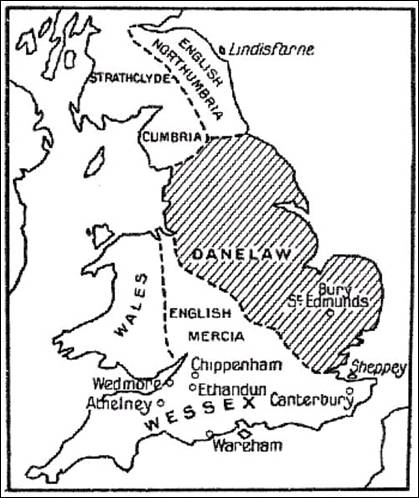

Danes gravitated to England (while Norwegians tended to be lured by The Emerald Isle). The Danish excursions to England began around 800, eventually leading to establishment of “The Danelaw.” As Gwyn Jones explains in her 2001 book, “A History of the Vikings”:

“The Danelaw was by name and definition that part of England in which Danish, not English, law and custom prevailed.”

|

|

|

Map showing Danelaw in Ninth Century England. |

She notes: “The Scandinavian basis of law and legal custom in the Danelaw was frequently and handsomely acknowledged by the law-makers of all England.”

The 884 Treaty of Alfred and Guthrum defined the boundaries between Danelaw, which comprised about one-third of England, and Wessex, to the west and south of Danelaw. Alfred, sometimes known as Alfred the Great, was king of Wessex; Guthrum was ruler of Danelaw.

Jones says that “though the Danelaw’s political independence lasted fifty years at most, its separate, i.e. Scandinavian, quality was recognized not only by Alfred and his English successors, but by the laws of Knut [king of England, Denmark, Norway and part of Sweden] in the early eleventh century and by Norman law-givers after the Conquest.”

As to the Vikings establishing in England the antecedents of the jury system, Donovan writes:

“The Danes brought laws to England, and ways to enforce them. In Scandinavia, they had recorded the laws via oral tradition; in England they committed them to writing. In 997, courts in the Danelaw were made up of twelve leading men, called thanes, who took an oath that they would not accuse the innocent or protect the guilty.”

![]()

James B. Thayer, a Harvard Law School professor who taught, among others, a future U.S. Supreme Court justice—Oliver Wendell Holmes—says in the May 15, 1891 edition of the Harvard Law Review:

“WHEN the Normans came into England they brought with them, not only a far more vigorous and searching kingly power than had been known there, but also a certain product of the exercise of this power by the Frankish kings and the Norman dukes; namely, the use of the inquisition in public administration, i.e., the practice of ascertaining facts by summoning together by public authority a number of people most likely, as being neighbors, to know and tell the truth, and calling for their answer under oath. This was the parent of the modern jury.”

Perhaps it would be more accurately denominated the parent of the grand jury.

R. C. Van Caenegem points out in his 1959 monograph, “Royal Writs in England from the Conquest to Glanvill” (as others have) that the twelve thanes (or “thegns”) were “clearly a jury of presentment.”

![]()

Various sources link the rudiments of the jury system in England to the Norman Invasion. For example, a 1966 Fifth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals opinion in Rabinowitz v. U. S., 366 F.2d 34, says that “[t]he sworn inquest of lawful men, the jury, came to England along with the Normans in 1066.”

|

|

|

KING ALFRED |

(The Normans were denizens of Normandy, a duchy in Northern France that had been established in 911 after the Vikings had established—with, perhaps, a bit of force—their presence there.)

While it appears certain that the forerunner of the grand jury existed in England earlier than 1066, some historical works contend that there was also use of a prototype of the modern petit jury before the Conquest.

“Reeves’ History of the English Law” by John Reeves and William Francis Finlason, published in 1869, says it is “manifest” that “juries were used in criminal cases in the time of Alfred,” AKA Alfred the Great, an Anglo-Saxon king who reigned from 871–899. The authors derive this from the “Mirror of Justices,” an early-14th century law book by Andrew Horn, chamberlain (financial officer) of the City of London.

Reeves and Finlason say the book tells of King Alfred having “caused several justices to be hanged for false judgment,” citing three of the circumstances for the hangings, set forth by Horn, relating to improper actions in connection with cases submitted to juries for decisions.

In a chapter on “Abuses,” Horn writes:

It is an abuse that justices and their officers who slay folk by false judgments are not destroyed like other homicides. And King Alfred in one year had forty-four judges hanged as homicides for their false judgments.

….

He hanged Eadwine, for that he judged Hathewy to death without the assent of all the jurors when he had put himself upon a jury of twelve men; and because three against nine were for saving him, Eadwine removed those three and put in their stead other three, upon whom Hathewy had never put himself.

….

He hanged Markes, for that he judged Duning to death upon the verdict of twelve men who had not been sworn.

….

He hanged Thurstan, for that he judged Thurgnor to death on a verdict taken ex officio on which Thurgnor had not put himself.

….

He hanged Freberne, for that he judged Harpin to death when the jurors were in doubt about their verdict, for in case of doubt one should rather save than condemn.

….

He hanged Thurbern, for that he judged Osgot to death for a deed of which he had already been acquitted as against the same plaintiff ; and Osgot offered to aver the acquittal by a jury, and Thurbern would not receive the allegation of acquittal because Osgot did not offer to aver it by the record.

….

He hanged the suitors of Cirencester for keeping a man in prison until he died in their prison, when that man was willing to acquit himself by a jury of ‘foreigners’ from the place where, as was alleged, he had sinned feloniously.

![]()

Other works insist that trial juries came to England later than the Conquest. Ralph Turner, in his 1968 essay, “The Origins of the Medieval English Jury,” published in the Journal of British Studies, scoffs that “the earliest Norman cases that anyone can cite in which there were juries date from the years just following the Conquest, 1070-79.”

He notes that in their 1966 book, “Law and Legislation from Aetheiberht to Magna Carta,” H.G. Richardson and G.O. Sayles “date the first Norman jury even later—in 1133.”

There appears to be every bit as much contention among historians as there is among majority and dissenting appellate court jurists. One critique, in a 1968 French historical journal, says the book by Richardson and Sayles “will satisfy few historians” and charges: “It is hypercritical or rather betrays a desire on the part of the authors to cast doubt at random on familiar and soundly established facts and ideas.”

What can be said with confidence is that the Norman Invasion did not spawn the modern jury system, any more than the system can be directly traced to the Magna Carta. Surely, on Oct. 15, 1066—the day after William the Conqueror led the Norwegian and French troops to victory at the Battle of Hastings—the first summonses for jury duty in an English court were not being issued—nor were they on Dec. 26 of that year, the day after William was crowned king of England.

There is, however, little clarity as to whether semblances of juries, as deciders of facts, existed before, or not until after, 1066.

![]()

Credit is due, in large part, to King Henry II (who reigned in England from 1133 to 1189) for the jury system in England becoming a permanent institution.

|

|

|

HENRY II |

Turner, in his 1968 essay, tells us that “juries were occasionally allowed in proceedings under the Norman kings, although they were not made available to all the king’s subjects until Henry II’s assizes.”

British historian William Chadwick, in his 1865 work, “King John of England: A History and Vindication,” attributes to Henry II “reforms in the administration of the law” including, he says, “giving encouragement to trial by jury, instead of the superstitious modes of trial by fire-and-water ordeals, and the still more barbarous one of single combat, especially in civil causes.”

While today, those with personal knowledge of a matter in controversy are, of course, barred from juries, Sir Patrick Devlin (later Lord Devlin), in a 1956 book, “Trial by Jury,” tells of jurors in the Twelfth Century who could serve only if they did possess (or professed to possess) such knowledge.

He writes:

“Henry [II] ordained that in a dispute about the title to land a litigant might obtain a royal writ to have a jury summoned to decide the matter….They were men drawn from the neighbourhood who were taken to have knowledge of all the relevant facts (anyone who was ignorant was rejected) and were bound to answer upon their oath and according to their knowledge which of the two disputants was entitled to the land. When a party got twelve oaths in his favour, he won. This is the origin of the trial jury, though there was as yet no sort of trial in the modern sense. It is also the origin of the rule that the trial jury consists of twelve…and also of the rule that the verdict of the twelve must be unanimous.”

“Modes of Trial in the Mediæval Boroughs of England” by Charles Gross, appearing in the May, 1902 issue of the “Harvard Law Review,” provides this information:

“Henry II’s Assize of Clarendon (1166) enacted that all indicted criminals should go to the ordeal of water; but about the year 1219 the fire and water tests were abolished and were soon replaced by the jury. In civil cases, also, this latter mode of trial rapidly gained ground since Henry II’s reign, so that by the middle of the thirteenth century it was applied by the royal judges to most civil and criminal suits.”

![]()

Providing a meaningful impetus to discontinuation of trial by ordeal was the pope.

The theory behind such a trial—entailing such tasks as walking over red-hot iron or snatching a stone from a pot of boiling water—was that God would protect the innocent. Three days after the ordeal, a priest would determine if God had intervened to heal.

In deterring that mode of trial, the pope, indirectly, advanced resort to a jury system.

Kenneth O. Morgan’s 2001 book, “The Oxford History of Britain,” advises:

“[I]n 1215 Pope Innocent III forbade the participation of priests in the ordeal and, in England at least, this meant that the system came to an abrupt end. After an initial period of confusion, trial by ordeal was replaced by trial by jury: this was a method which had already been used with some success in settling disputes about possession of land. In 1179 Henry II had ordered that, in a case concerning property rights, the defendant might opt for trial by jury rather than trial by battle—the method which had been introduced into England by the Normans and the efficacy of which, like the ordeal, was vulnerable to doubt. But this rule when applied to criminal justice meant that there was a trial only when the accused opted for one. Obviously he came under great pressure. By a statute of 1275 he was condemned to a ‘prisone forte et dure’ until he did opt for trial. In consequence, many men died in prison, but because they had not been convicted, their property was not forfeited to the Crown. For this reason some chose to die rather than risk trial. Not until the eighteenth century was this right to choose taken away.”

![]()

So, just when did the jury, as we know it, make its debut?

Barrister/author J.E.R. Stephens, in “The Growth of Trial by Jury in England,” published in the Harvard Law Review in 1896, reflects:

“The foundation of the institution of trial by jury was not laid in any act of the legislature, but it arose silently and gradually out of the usages of a state of society which has forever passed away.”

Copyright 2015, Metropolitan News Company