Monday, January 12, 2015

Page 2

PERSONALITY PROFILE:

JACKIE LACEY

She Is Where She Is Through Hard Work, Skill, and Confidence Placed in Her by Steve Cooley

By KENNETH OFGANG, Staff Writer

|

G |

rowing up less than five miles from the University of Southern California, in the early 1960s, Jackie Lacey says now, she never thought about attending the prestigious university.

She knew it as the school “where the wealthy people go,” she reflects. And yet, by the 1980s, she literally became a symbol of its efforts to attract a more diverse student body, and in 2010 she came to its new arena to be sworn in as the 42nd district attorney of Los Angeles County.

The path to that office began at UCLA Medical Center, where she was born Jackie Phillips. Living in the Washington-Adams area and later the Crenshaw district, her father worked for the City of Los Angeles in what was then called the Lot Cleaning Division, while her mother worked at a sewing factory in the downtown garment district before securing a job as a cook in the Los Angeles Unified School District.

They were Christians, members of the large Trinity Baptist Church, and the church was “everything,” Lacey—who wears a wristband inscribed “WWJD?” (What Would Jesus Do?)—says.

“We were Southern Baptists,” she says. “….That means you go to Sunday school, then you go to church and you’re there ‘till about 2:30, then you go home and eat dinner and then you come back for Baptist Youth Fellowship, then you come back on Wednesday for prayer meeting. So our lives pretty much revolved around the Baptist church.”

But the church was, and is, far more than prayer and Bible study, she explains. For her family, like many African Americans, the church was “very much” a political, social, and economic institution.

“Every politician running for everything came by on Sunday,” she recalls.

The church was also active in registering voters and held political breakfasts on Saturdays, so the future district attorney was exposed at an early age to judges and local, state, and federal lawmakers.

Attends UC Irvine

Graduating from Dorsey High School in 1975, and with a choice of colleges to attend, she chose UC Irvine. “I wanted to get away from home, but not too far,” she says, so she picked a school where she could live on campus but come home on weekends.

UCI had a “beautiful, welcoming campus,” she says, and notes that she remains close to some of the friends she made there.

Her goal at the time, she relates, was to become a teacher, and she thought that majoring in psychology would be a way to get there. But she eventually concluded that “teaching was not something I was called to do.”

As fate would have it, she explains, her search for “easy credits” in her junior year took her to a course called “Introduction to the Study of Law.” Her understanding when she signed up, she explains, was that all she had to do was to show up in a courtroom once a week, watch cases, attend lectures by lawyers and judges one other day each week, and write a paper at the end of the term.

What she discovered, she says now, was that she was “just gripped by the courtroom scene.”

Irma Brown Inspires

But what cinched her decision to apply to law school, she says, was a talk by a “young, very hip African American woman lawyer” from Los Angeles named Irma Brown.

Brown, now a Los Angeles Superior Court judge, was president of the Black Women Lawyers of Los Angeles at the time. What stood out about Brown, besides her youth, gender, and race, Lacey remembers, was the pride she expressed in her profession.

“Listening to her made me think, ‘I could do what this woman does for a living,’ “Lacey says. “After that, I was on a mission to go to law school.”

|

|

|

Jackie Lacey is the 42nd district attorney of Los Angeles County. |

She was ultimately accepted for admission at Hastings College of the Law, and USC. She expected to go to Hastings, she explains, because as part of the UC system, it charged far less in tuition.

But she was sufficiently “intrigued” by the school she grew up near that she accepted an invitation for a tour. “I wanted to see what I was turning down,” she says.

A meeting with the dean of admissions proved beneficial, she recollects.

“He asked me, ‘What would get you to choose USC?’ And I said, ‘Quite frankly, it’s the money issue.’…About a month later, I got a letter in the mail saying, ‘We are offering you a full tuition scholarship’…and that made me choose USC.”

She’s glad she did, she says in retrospect.

In 1980, at the end of her first year of law school, she married David Lacey, an accountant, whom she had met when she was 17 and dated all through undergraduate school. They moved into a campus studio apartment that she says was smaller than her current personal office in the Foltz Criminal Justice Center. (She’s scheduled to move into the renovated Hall of Justice next month.)

Less than a year later, she discovered she was pregnant with her son, who was born in the fall of 1981. “We were worried about interrupting my studies,” she says, and she returned to classes two weeks after her first child was born.

She proudly points to a USC magazine that she keeps on her desk, showing a photo taken at graduation of herself, her husband, and their infant son. The law school, she notes, used the picture in its admissions catalogue the following year.

Being a mom and a law student at the same time was “tough,” she says, adding: “I wouldn’t do that again.”

Her second child, a daughter, was born in September 1983, two months after she took the bar exam. She stayed home for a year before joining the Arthur Leeds Law Corporation, a small Century City firm that practiced civil litigation and entertainment law.

“I was bored to tears,” she says. “The breaking point,” she recounts, was when she had to sit in on a deposition of one of the firm’s clients, “listening to one of the lawyers object over and over again,” and began thinking “if this is what I’m going to be doing for the rest of my life, I have made a big mistake.”

It was a far cry from the excitement she observed in that introductory course at UCI, she says.

Becomes a Prosecutor

Not long after that, she recites, she was talking to Rhonda Saunders, a USC classmate who became a deputy district attorney. Saunders told Lacey about some openings for misdemeanor prosecutors at the Santa Monica City Attorney’s Office.

Lacey applied, was hired, and was trying cases within a few weeks.

“I was hooked,” she says. “I remember thinking, ‘This is what I was born to do, to be a trial lawyer.’ ”

After 18 months in Santa Monica, she was hired by the district attorney as a felony prosecutor. Like other young lawyers in the office, she handled a series of assignments in different parts of the county.

One of those assignment changes proved a significant event in her career path.

While doing felony work in the San Fernando Valley, she received a call asking whether she would be interested in a new post handling zoning cases. The less-than-glamorous-sounding task required travel all over the county, she explains, but offered a more flexible schedule, perfect for a mother of small children.

Bearded Colleague

One of the courts she had to travel to was in the Antelope Valley, where she met a senior deputy she recalls as having “a beard and brown shaggy hair.” His name was Steve Cooley, “and it was almost an instant like for both of us,” she says.

“He was engaging, friendly, and we would talk” whenever she went back to that courthouse, Lacey says.

Cooley was subsequently named head deputy in San Fernando, under the then-newly elected district attorney, Gil Garcetti, and Lacey wound up being assigned there.

Cooley “was a good boss,” she remarks. “He gave you cases where you could grow.”

For Lacey, that included “some of her most important trial work” including her first death penalty prosecution and a serial child molester case. By the time Cooley challenged Garcetti for reelection, in 2000, she was one of the more senior deputies in the Valley and handling a caseload she describes as “challenging.”

Cooley won the election and was sworn in as district attorney in December 2000.

But a strange thing happened right before he took office.

Lacey says she was on the train to work, when a fellow employee saw her and offered congratulations. “I said, ‘What are you talking about?’ ”

It seems Cooley had gone on the KCET local news show “Life and Times Tonight” the previous evening and announced the first members of his executive team, including Lacey as director of the Bureau of Central Operations.

Taken by surprise, she relates, she immediately called Cooley. She chuckles as she recalls his response: “You know, I meant to tell you that before I announced it.”

Not only was she not expecting the job, she comments, “I didn’t even know what a director did.”

It was an unusual promotion, Lacey says. While each district attorney gets to select his or her own executive team, she notes, the upper echelon of the office is traditionally made up of people who have worked their way up the management ladder, usually starting with service as a deputy-in-charge of a small office.

Cooley Lacked Doubt

Instead, Lacey was jumping from a trial deputy post, albeit a senior one, to being in charge of 200 employees when she had, she admits, “no management training whatsoever.” Lacey remembers it being difficult, but Cooley said he never doubted he had made the right choice.

Lacey was “smart, hardworking,” he explains. After supervising her for more than four years, he says, “I knew she could do the job.”

For Lacey, it came down to “the principles I used at being a mom—treat people like you want to be treated, criticize constructively in private, and praise in public.”

Management can be “very isolating,” she notes. It often means “you have to tell people things they may not be happy with” and recognize that “people treat you differently when you have a title,” thinking they have to “suck up a bit to get ahead.”

As the first three-term district attorney in well over a half-century, Cooley had more than one occasion to shake up his team. Lacey spent the 12 years of his tenure in a number of posts, eventually moving up to assistant district attorney—the No. 3 job—and then chief deputy, meaning she outranked every prosecutor in the county except Cooley.

Most of her positions involved guiding the courtroom prosecutors and making decisions involving important cases, she explains, while serving as chief deputy made her more involved in personnel issues.

Then, in December 2009, Cooley let it be known he was on the verge of running for state attorney general, something his chief deputy expected but hadn’t been told.

“I had to learn about it in the MetNews,” she complains.

Eyed DA Post

The news that her boss was going to run for another office, she acknowledges, got her thinking about her own future, but not in terms of an election campaign.

“I thought Steve was going to win,” she explains, meaning the county supervisors would choose his successor, an appointment she was potentially positioned to get. But when Cooley lost a close race to Kamala Harris that November, Lacey says, “I knew he did not want to run” for a fourth term as district attorney, and she “was imagining that I could be D.A.”

So she made the decision, in December 2010, that she would run in the June 2012 primary, officially launching the campaign the following spring. But she knew it was going to be a “tremendous fight,” she says.

“I knew I wanted the job,” she says. “I did not know if I wanted to be out all night, every night, raising $1 million, $1,500 or less at a time.”

Political observers were expressing skepticism. They said the campaign looked like it was stuck in place, and Lacey says they were right.

“The first six months of my campaign, I did not have the right team,” she says, in retrospect. Money was tight, and “people were not taking my campaign seriously.”

The obvious move, she says, was to “part ways” with her campaign consultant. But that gave the appearance of a sinking ship, and soon the manager handling day-to-day campaign activities and the campaign’s professional fundraiser “just quit,” Lacey says.

Hires Parke Skelton

“I was pretty embarrassed,” she admits, before she hired Democratic heavyweight Parke Skelton’s firm, SG&A Campaigns.

She wasn’t sure Skelton, who had seemed disinterested the first time she spoke to him, would take on the foundering campaign, Lacey says. But after they met, she recalls, he told her what she needed to hear: “I’m going to run your campaign, because I think you would be a great DA.”

Of all the consultants she spoke to, she says, he was the first to talk about the campaign in terms of her qualifications, rather than her likelihood of success. And he was the only one who grasped the significance of Cooley’s endorsement, she notes.

He did a “fantastic” job, she exclaims, giving the campaign an instant boost. Skelton came aboard in October 2011, an attorney friend was hired as the day-to-day manager, new fundraisers were brought in, and by April, wealthy supporters were beginning to fill the coffers with huge chunks of money.

“The watershed moment,” she recalls, came on Mother’s Day, when the Los Angeles Times gave her its endorsement.

Trutanich Was Frontrunner

Lacey says she agreed with the conventional wisdom at the time, that she and the other deputy district attorneys in the race were battling for second place behind Los Angeles City Attorney Carmen Trutanich, who had outraised the field and had the endorsements of the governor and organized labor.

“My thought was: if I get into second place, I could beat him in the runoff,” she says.

While a bit of luster came off Trutanich’s campaign near primary day, as he dealt with claims he had fabricated a long-told story about his coming under fire from gang members during his days in the District Attorney’s Office, Lacey says she still expected him to lead on election night. So when a reporter came up to her not long after the polls closed and told her she was in first place on the early absentee ballot count, with Deputy District Attorney Alan Jackson in second and Trutanich third, she says, her reaction was, “You have got to be kidding.’”

|

|

|

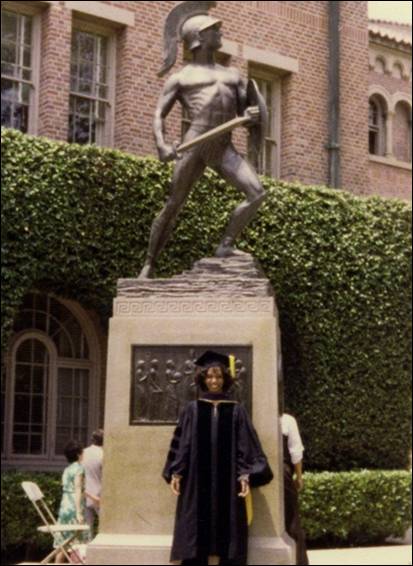

University of Southern California law school graduate Jackie Lacey on the university’s campus. |

But that result held all night, and so Lacey and the team went straight to work on a campaign for the runoff they had hoped to be in, but with an opponent they had not expected to face.

She and Jackson “had a cordial working relationship, and a cordial relationship on the campaign trail,” she says, although things got a little testy in the runoff. Lacey says she was “focused on the positives”—getting out the message that she was the candidate with both trial and management experience.

Although the campaigns sniped in the press over things like which felon donated to which campaign, and whether Lacey’s management experience was a positive or her 13-year absence from the courtroom was a negative, Lacey focused on raising money, at which she was far more successful than Jackson in the closing days. That enabled the campaign to put out “six million pieces of mail,” Skelton told a political blogger.

She also inherited much of the labor and law enforcement support that had gone to Trutanich, and won the race with 55 percent of the vote.

The past two years have gone by quickly, she says, as the office fights to keep up with the changes in criminal laws.

First it was realignment, which passed when she was still chief deputy and which has, she says, resulted in many offenders who would otherwise be in prison becoming the responsibility of local law enforcement. It’s been a challenge, she says, and getting accurate information on recidivism rates has been difficult, but she takes heart in statistics showing that all categories of violent crime, except aggravated assault, remain lower than they were a few years ago.

Lacey also notes that she came into office at the same time that Proposition 36, the reform of three-strikes sentencing, was approved, and her office has had to review more than 1,000 petitions by inmates seeking to be resentenced. The law requires that the district attorney, if opposed to resentencing, prove that there is an unreasonable risk that the inmate’s release will endanger the community.

Proposition 47

The most recent challenge, she says, results from the passage this past November of Proposition 47, which reduced a number of felonies to misdemeanors. The law, which Lacey says is having a great many unintended consequences, took effect the day after the election and is fully retroactive.

Fortunately, she says, she has had cooperation from other agencies, in particular the Los Angeles City Attorney’s Office, which has agreed to give her deputies joint appointments, so that they can finish work on their felony-turned-to-misdemeanor cases rather than have to hand them over in midstream.

She is also pleased, she says, to be working with fellow Person of the Year honoree Jim McDonnell, whom she supported for election as sheriff. Having known him since he served under then-LAPD Chief Bill Bratton, she says, she regards him as “a good guy with a great heart, the kind of leader who inspires others to do their best.”

She finds what has occurred in the Sheriff’s Department the last few years “disheartening,” she says. “When bad people are in control…it affects the morale and the effectiveness of the entire department,” she remarks, praising the work done by McDonnell and the other members of the Citizens’ Commission on Jail Violence.

And she looks forward to sharing the reopened Hall of Justice with McDonnell and his staff, she says.

____________________________________________________

Tributes to Lacey

Jackie is the personification of elegance and cool. In the most sensitive of matters, under extreme pressure, Jackie always remains calm, focused and legally correct. She has unified the LA County DA’s office into a very effective prosecutorial office with outstanding results. I can tell you from personal experience and friendship with Jackie, she is simply and outstanding Justice Partner who is highly respected by the courts, the law enforcement community, the Board of Supervisors and her staff. A truly wonderful friend one could not ask for anyone better.

BRENT BRAUN

Attorney at Law,

Former Supervisory Special Agent, FBI

Whenever someone of stature leaves, his or her successor is bestowed with the over-used phrase of You’ve got some big shoes to fill.” Well, not only did Jackie fill Steve Cooley’s shoes, but she firmly set down her own path, so the next person will have some “big heels to fill.” Jackie has changed the image of what a prosecutor should and can do. Her true passion for justice and reputation of great integrity makes Los Angeles County a great model for other prosecutors to follow as we move to achieve greater justice. Felicidades on your award.

LUIS J. RODRIGUEZ

Division Chief

Law Offices of the Los Angeles County Public Defender,

Former President, State Bar of California

Jackie Lacey has dedicated her career to protecting and bettering her community. She has been a pioneer in innovative alternatives to incarceration and a tireless supporter of the Veterans Courts Programs. With a keen understanding of the complex issue of mental illness and the effect it has on our communities, our D.A. has been committed to responding to the needs of the community she serves. An invaluable public servant with the initiative and passion to take on issues like animal cruelty, graffiti and gang violence make it a surprise to no one that Los Angeles District Attorney Jackie Lacey is named as one of the Persons of the Year by Metropolitan News-Enterprise.

RICHARD BLOOM

Member of the Assembly

District Attorney Jackie Lacey is a classic “up from the ranks” professional, non-political district attorney. From code enforcement deputy district attorney in the Antelope Valley to the top of the largest local prosecution office in the world, she has excelled at all the demanding jobs of a prosecutor and done so with consummate grace and good humor. She has made her mark early in her tenure as D.A. with ground-breaking initiatives such as special programs for mentally ill defendants while motivating her deputies and investigators to continue to vigorously pursue their commitment to protect the public in the face of the strictures visited on them by the ill- founded Assembly Bill 109 and Proposition 47. She is respected statewide and nationally for her achievements.

ROBERT H. PHILIBOSIAN

Of Counsel,

Sheppard Mullin Richter & Hampton LLP,

Former Los Angeles County District Attorney

Copyright 2015, Metropolitan News Company