Thursday, April 23, 2015

Page 1

Ninth Circuit Throws Out Barry Bonds’ Conviction

En Banc Court, While Sharply Split as to Rationale, Agrees That ‘Rambling Non-Response’ Wasn’t a Crime

From Staff and Wire Service Reports

Barry Bonds’ obstruction of justice conviction was thrown out Wednesday by the Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, which ruled 10-1 that his meandering answer before a grand jury in 2003 was not material to the government’s investigation into illegal steroids distribution.

|

|

|

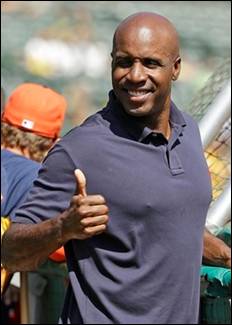

—AP In this file photo, career home run leader Barry Bonds gives a thumbs up while standing behind the batting cage and watching the Houston Astros take batting practice before the start of the baseball game against the Oakland Athletics in Oakland. |

No single rationale commanded a majority of the court, so the per curiam majority opinion was only two paragraphs long. The majority was able to agree only that Bonds’ “rambling non-response” was immaterial and that the Double Jeopardy Clause bars retrial.

Following a trial that opened in March 2011, a jury deadlocked on three counts charging Bonds with making false statements when he denied receiving steroids and human growth hormone from trainer Greg Anderson and denied receiving injections from Anderson or his associates.

Bonds was convicted for his response when he was asked whether Anderson ever gave him “anything that required a syringe to inject yourself with.”

“That’s what keeps our friendship,” Bonds said. “I was a celebrity child, not just in baseball by my own instincts. I became a celebrity child with a famous father. I just don’t get into other people’s business because of my father’s situation, you see.”

Kozinski Concurrence

Judge Alex Kozinski, in one of four concurring opinions, explained that “[r]eal-life witness examinations, unlike those in movies and on television, invariably are littered with non-responsive and irrelevant answers.” Bonds’ response, he said, “says absolutely nothing pertinent to the subject of the grand jury’s investigation,” even when read in connection with the question about Anderson giving him something that required an injection.

Kozinski said the obstruction statute, “stretched to its limits ... poses a significant hazard for everyone involved in our system of justice, because so much of what the adversary process calls for could be construed as obstruction.”

“One need not spend much time in one of our courtrooms to hear lawyers dancing around questions from the bench rather than giving pithy, direct answers,” he wrote. Read in the context of Bonds’ entire testimony, Kozinski wrote, “the otherwise innocuous” answer cannot be held material. If it could, he said, “few witnesses or lawyers would be safe from prosecution.”

Kozinski was joined by Judges Diarmuid O’Scannlain, Susan Graber, Consuelo Callahan, and Jacqueline Nguyen.

Judge N. Randy Smith, joined by Callahan and Judges Kim Wardlaw and Michelle Friedland, argued that giving “a single truthful bueline Nguyen.

Judge N. Randy Smith, joined by Callahan and Judges Kim Wardlaw and Michelle Friedland, argued that giving “a single truthful but evasive or misleading answer” is not obstruction of justice.

Reinhardt’s View

Judge Stephen Reinhardt argued that the obstruction-of-justice statute was never intended to apply to witness testimony, while Judge William Fletcher said the statutory element of having acted “corruptly” is limited to acting by force, threats, or bribery.

The lone dissenter, Judge Johnnie B. Rawlinson, wrote an opinion filled with baseball references that began “there is no joy in this dissenting judge,” added the judges who sided with Bonds “have struck out” and concluded “I cry foul.”

While Bonds’ response included “extended responses to unasked questions,” the dissenting judge wrote, he “studiously avoided answering the question that was actually asked: ‘Did [Anderson] ever give you anything that required a syringe to inject yourself with?’”

That avoidance, Rawlinson argued, corruptly obstructed justice because the testimony of other witnesses clearly established that the answer was yes. The court’s contrary ruling, she said, was insufficiently deferential to the jury and fails to distinguish between perjury and obstruction of justice.

Eight-Year Fight

Bonds, whose 762 home runs broke Hank Aaron’s long-standing career record of 755, was indicted in 2007 for his testimony four years earlier before the grand jury investigating the Bay Area Laboratory Co-Operative, commonly known as BALCO, which allegedly supplied Bonds and other athletes with performance-enhancing drugs.

“Today’s news is something that I have long hoped for,” Bonds said in a statement. “I am humbled and truly thankful for the outcome as well as the opportunity our judicial system affords to all individuals to seek justice. ... I am excited about what the future holds for me as I embark on the next chapter.”

BALCO founder Victor Conte said he “could not be more happy that Barry Bonds finally gets to move on with his life,” and that he hoped “the prosecutors choose not to waste any more resources on what has been nothing more than a frivolous trophy-hunt and a complete waste of taxpayer dollars.”

Jessica Wolfram, one of the jurors who convicted Bonds following the three-week trial and four days of deliberations, said she couldn’t help but feel the decade-long prosecution was “all a waste, all for nothing.”

“Just a waste of money, having the whole trial and jury,” she said in a telephone interview with The Associated Press.

Travis Tygart, chief executive officer of the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency, believed the decision was “almost meaningless for the real issue, which is whether he used performance-enhancing drugs to cheat the fans of baseball.”

He said:

“I think at the end of the day America knows the truth and who the real home run record holder is, who did it the right way, and it’s obviously not Barry Bonds.”

A seven-time NL MVP and the son of three-time All-Star Bobby Bonds, Barry Bonds was sentenced in 2011 by U.S. District Judge Susan Illston to 30 days of home confinement, two years of probation, 250 hours of community service in youth-related activities and a $4,000 fine. He already has served the home confinement.

Illston declared a mistrial on the three other counts, and the U.S. attorney’s office in San Francisco dismissed those charges in August 2011.

A three-judge panel of the Ninth Circuit upheld the conviction in a unanimous vote in 2013, but a majority of the court’s 28 participating judges voted to have an 11-judge en banc panel rehear the case. None of the original three judges—Mary Schroeder, Michael Daly Hawkins, and Mary Murguia—were randomly selected for the en banc court.

Bonds’ appellate lawyer, Dennis Riordan commented that “[t]he greatest impact [of the opinion] is the damage it undid” by wiping out “a panel opinion that said if you’re asked a question on page 78 and you digress before you answer it directly on page 81, you’re a federal felon.”

The case is United States v. Bonds, 11-10669.

Copyright 2015, Metropolitan News Company