Tuesday, April 29, 2014

Page 1

S.C. Upholds Death Sentence for Serial Killer Suff

Court Says Public Defender Properly Disqualified Over Defendant’s Objection Due to ‘Staggering’ Conflict

By KENNETH OFGANG, Staff Writer

The state Supreme Court yesterday unanimously upheld the death sentence for William Suff of Riverside County, convicted of murdering 12 women between 1989 and 1991.

Justices rejected the defendant’s claim that Riverside Superior Court Judge Charles W. Morgan deprived him of his right to counsel by disqualifying the public defender from representing him, despite his understanding of, and willingness to waive, the conflict. The high court said the judge acted within his discretion, given the “staggering” nature of the conflict.

|

|

|

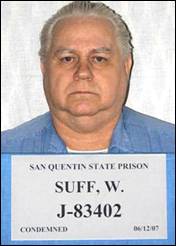

—California Department of Corrections WILLIAM SUFF Death Row Inmate |

Most of the victims, and many potential prosecution witnesses, were mostly prostitutes with past involvement in the criminal justice system. Testimony at a hearing on the prosecution’s motion to disqualify the public defender revealed that the office had represented the victims or witnesses in 56 separate matters, and that 25 of the lawyers in those cases were still with the office.

In addition, prosecutors said, 11 of their witnesses had specifically refused to waive attorney-client privilege with respect to communications with public defender personnel.

Replacing the public defender with counsel from the county conflicts panel did not, in those circumstances, violate Suff’s right to counsel, regardless of his objections, Chief Justice Tani Cantil-Sakuye wrote for the court. There is no constitutional right to be represented by appointed counsel of one’s choosing, she said.

Claims Rejected

The court also rejected claims that Suff did not get a fair trial due to extensive pretrial publicity, that evidence obtained in a search of the defendant’s vehicle was the product of an unlawful stop, that the defense should have been allowed to present evidence of other prostitute murders to support its theory that someone else was the killer and that the crimes continued after Suff was arrested, and that incriminating statements by the defendant to the lead detective were obtained in violation of the right to freedom from self-incrimination.

Jurors, who reportedly took only 10 minutes to agree that Suff was guilty of 12 of the 13 murders with which he was charged, heard evidence linking the defendant to the murders of Kimberly Lyttle, Christina Leal, Darla Ferguson, Carol Miller, Cheryl Coker, Susan Sternfeld, Kathleen Milne Puckett, Sherry Latham, Kelly Hammond, Catherine McDonald, Delliah Zamora, and Eleanore Ojeda Casares. All were killed between 1989 and 1991.

Jurors deadlocked 11-1 for conviction on the remaining murder charge. The body of that victim, Cherie Payseur, was found behind a bowling alley.

The jury also convicted Suff of the attempted January 1989 murder of Rhonda Jetmore, an admitted prostitute who escaped and identified him as her attacker.

Much of the defense argument on appeal was focused on the January 1992 traffic stop by Riverside Police Officer Frank Orta. The officer testified that he was on routine motorcycle patrol in the vicinity of University Ave. in Riverside, an area of much prostitution activity, where a majority of the murdered women were believed to have been working before they disappeared.

Van Description

Orta said he spotted a van, which turned out to be driven by Suff. He thought the vehicle looked like the one described as having been driven by a suspect in the serial killings, he said, adding that a woman who looked like a prostitute approached the van but moved away when she saw Orta.

The officer said he followed the van, intending to make contact with the driver, and was right behind the van when it stopped for a red light. When the driver “suddenly made a right turn without any kind of signals or without moving over towards the curb,” Orta said, he stopped the van for failing to signal the turn.

When Suff produced an expired driver’s license and no registration, the officer began writing a citation, and also ran a vehicle registration check showing that the registration had expired over a year earlier. Orta then impounded the vehicle; he testified that he always impounded vehicles when their registrations were expired by more than a year. The vehicle was searched, resulting in the discovery of a pellet gun, a knife with apparent blood on it, and fibers consistent with those found at several of the murder scenes.

Police arrested Suff for violating parole on a Texas murder conviction, and took him to the local police station for questioning.

After the detective made it clear that she believed he was connected to the prostitute murders, he said:

“I need to know, am I being charged with this, because if I’m being charged with this I think I need a lawyer.”

After the detective responded “[w]ell at this point, no you’re not being charged with this,” and the defendant then consented to a search of his apartment.

Suff eventually admitted that he was in an orange grove where Cazares’ body was found, had seen the body with a knife in it, and had removed the knife and put it in his van. When one of the detectives asked him “about the body you left there,” he said, “I better get a lawyer now. I better get a lawyer, because you think I did it and I didn’t.”

Morgan eventually denied defense motions to suppress the evidence obtained in the traffic stop, as well as Suff’s admissions regarding the body in the orange grove.

Both rulings were correct, the high court concluded.

The traffic stop, the chief justice explained, required no justification beyond Suff’s violation of the statutory requirement that a driver signal a turn “in the event any other vehicle may be affected by the movement.” The jurist noted that Orta’s motorcycle was directly behind Suff, and that the statute refers to whether a “vehicle” will be affected, not whether “traffic” will be affected.

As to the interrogation, she said, Suff’s conditional comment about needing a lawyer was too ambiguous to be an invocation of the right to counsel or to remain silent.

Noting that the detective truthfully told Suff he was not being charged with murder “at this point,” the chief justice wrote:

“The focus of the test…is the clarity of the defendant’s request, not the particular officer’s belief, and there is no requirement that an officer ask clarifying questions...

“Miranda requires that the person in custody be informed of the right to remain silent, the consequences of forgoing that right, the right to counsel, and that if the person is indigent, a lawyer will be appointed….There is no requirement that, before a person may validly waive his privilege against self-incrimination, he must be apprised of the evidence against him, the ‘severity of his predicament,’ or the chances he will be charged.”

Justices Marvin Baxter, Kathryn Werdegar, Carol Corrigan, and Ming Chin, and retired Justice Joyce L. Kennard, sitting by assignment, joined Cantil-Sakauye’s opinion.

Justice Goodwin Liu argued in a separate concurrence that the questioning of Suff should have ceased when he commented about needing a lawyer.

The justice reasoned:

“Detective Keers was the lead investigator on this case. Given what she knew during the interrogation, she could not have had any doubt that defendant would be charged with these murders. By telling defendant, ‘Well at this point, no you’re not being charged with this,’ she misled him. As Miranda said, ‘any evidence that the accused was threatened, tricked, or cajoled into a waiver will, of course, show that the defendant did not voluntarily waive his privilege.’”

The constitutional violation was harmless beyond a doubt, however, “given the other evidence of defendant’s guilt,” he wrote.

Riverside District Attorney Paul Zellerbach, who was the prosecutor at Suff’s trial, told the Riverside Press-Enterprise yesterday that the high court’s decision “is attributable to all the hard work and effort of the dozens of law enforcement personnel who worked on that investigation and brought in and analyzed evidence from the crime scenes for years.”

Frank Peasley, the defense attorney who represented Suff during the trial, told the Press-Enterprise that the delay in resolving the case—19 years from sentencing to yesterday, and what he predicted would be 10 years of further proceedings—was “unbelievable” and “one of the great arguments against the death penalty.”

The case is People v. Suff, 14 S.O.S. 2048.

Copyright 2014, Metropolitan News Company