Monday, January 13, 2014

Page 5

PERSONALITY PROFILE:

DAVID & CYNTHIA PASTERNAK

He’s a ‘Workhorse,’ She’s a ‘Bulldog’…Together, They’re a ‘Powerhouse Couple’

By a MetNews Staff Writer

|

D |

AVID PASTERNAK SETTLES IN BEHIND HIS DESK AT HIS CENTURY CITY OFFICE and begins to tell a story of his college days at UCLA, while his wife, Cynthia, looks on from a nearby chair after joining him from her own adjacent office.

Together, they head up the law corporation of Pasternak & Pasternak. Over the span of nearly four decades, they have each served in numerous leadership positions in bar associations—including his presidency of the Los Angeles Country Bar Association and her presidency of the Beverly Hills Bar Association—and in charitable organizations. Each is the recipient of various professional honors.

In addition to their experience as respected litigators, David Pasternak has established himself as one of the leading court receivers in California, while Cynthia Pasternak has developed a reputation as one of the region’s premier mediators.

|

|

|

Cynthia and David Pasternak on their wedding day. |

“I have known David and Cindy Pasternak for almost 30 years and have worked closely with each in their service to the bar, the courts and the public,” Patrick M. Kelly, the immediate past State Bar president, says. “Each has made a tremendous contribution to the profession and the community and together they are truly a ‘powerhouse’ couple in their service,”

In the same vein, Diane Karpman, who has held leadership positions in various bar groups, terms the Pasternaks “the original power couple,” adding: “Both are absolutely committed to the legal profession.”

For their accomplishments and leadership within the legal community, both as individuals and as a couple, David and Cynthia Pasternak have each been designated as a 2013 MetNews Person of the Year.

Destined to Be Together

It seems destined that the couple would end up together, given the overlap in their childhood and educational experiences.

Both were born in New York City, and were brought to Los Angeles as infants, where they have stayed ever since. Both are the oldest of three siblings. They both attended UCLA as college undergraduates during the same years and had the same majors, but never managed to cross paths there. They also attended law school together at Loyola Law School of Los Angeles, where they first met. But it wasn’t until well after their law school graduation that they started dating.

“We only had one class together in law school,” Cynthia Pasternak recalls—a sales class. “We sat next to each other because it was alphabetical,” she says, noting that her maiden name was Rosen.

At the time, however, David Pasternak was married to his first wife, whom he had wed after college. Cynthia Pasternak was dating a man whom she eventually married after law school.

After they both graduated from Loyola in 1976, the two continued to cross paths years later when they each got involved in Los Angeles County Bar Association activities and ended up working near each other in Century City. Cynthia Pasternak was an associate with the firm of Irwin, Hale and Jacobs. David Pasternak was with Tyre & Kamins.

“Once in a while, we’d have lunch together since we were both working in Century City,” David Pasternak says. “They were just professional lunches. It was getting together with a former classmate and fellow attorney.”

By 1986, Cynthia Pasternak had divorced her first husband and was rearing her first son on her own while working full time. David Pasternak had separated from his own spouse after 13 years of marriage.

Cynthia Pasternak recalls the time that year when they started dating:

“There was a one week period in Century City where every single day at lunch time, we either walked by each other or sat at a table next to each other at various restaurants. He said he would call me to get together. So he calls me up that Friday and I said, ‘Let me look at my calendar. I’m available next week for lunch.’ He said, ‘I was thinking dinner.’ ”

David Pasternak chimes in:

“There was hesitation on her part. Sort of silent. And I said, ‘I’m separated.’ At which point she said, ‘Oh, I’d love to!’ ”

His wife corrects him.

“I said, ‘I’d love to,’ but not with such enthusiasm,” she says.

They dined the next Tuesday night at the Ritz Cafe on Pico Boulevard. Cynthia Pasternak provides this account:

“We just talked, talked, talked, and by the end of the evening, I hadn’t noticed anybody else. We really hit it off.

“The next day, I got flowers. I’m looking at the card, and he has the worst signature in the world. So he calls me up in the afternoon and asked how I was, and I said, ‘I’m doing great. I got these lovely flowers from somebody named Phil.’ His signature looked like ‘Phil.’

“He laughed, and asked me out again for that Saturday night. We were an item right away.”

They were wed two years later.

“We got married the night Kirk Gibson hit the home run to win the Dodger game in the World Series,” David Pasternak interjects. That date would be Oct. 15, 1988.

Together, they have three children, all sons. Greg, 32, is from Cynthia Pasternak’s first marriage. He is an actor and entertainer. Kevin, 23, is a law student at Loyola. Their youngest, Matthew, is 20, and studies industrial design at Syracuse University.

David and Cynthia Pasternak remain inseparable to this day, not only in the marital sense, but also as the heads of the law firm bearing their names. Although Cynthia Pasternak last November moved her mediation practice to ADR Services, she says that she continues to “help manage, advise, negotiate and handle other legal matters for Pasternak & Pasternak.”

David Pasternak

David J. Pasternak was born in New York City on March 5, 1951. His parents, Rubin and Esther Pasternak, moved him and the family to Los Angeles in 1953, when he was 2. By the time he was 6, the family had settled in Sherman Oaks.

“It was what people were doing during that era,” Pasternak says. “People were moving to California and they saw it as the land of opportunity.”

His father was born in Poland and had moved to New York after surviving the Holocaust. His mother was from New York, where they met. Rubin Pasternak was a wholesale furrier for most of life, while Esther Pasternak was a homemaker.

David Pasternak attended Grant High School in Van Nuys.

|

|

|

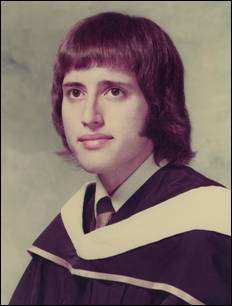

UCLA graduate David Pasternak. |

“Until 11th grade, I never took high school seriously,” he reflects. “I knew I was going to go to college. I knew when I was probably about 12 years old that I wanted to become a lawyer, and so I knew I needed to get good grades to get into college and law school.

“I had a B average. Then all of a sudden I realized in 11th grade I didn’t have the grades to do what I wanted to. So I applied myself and got straight As one semester. After that, I got into UCLA.”

There was no specific event that made David Pasternak know that he wanted to become a lawyer at such a young age. No court case. No movie. No legal headline. He just knew.

“I never spoke to a lawyer or judge before I started law school,” he says. It was just something that interested me.”

Initially, his goal was to become a transactional lawyer.

Pasternak entered UCLA in 1969 and, with plans to attend law school, he tailored his studies accordingly. He majored in political science and emphasized English classes over the physical sciences. While taking classes, he worked on-campus at the university research library, first as a key-punch card operator, then as a computer operator.

Pasternak recalls his college days fondly.

“I loved UCLA,” he says. “It was an exciting time to be a college student in the early ’70s. Politically. Socially. Culturally.”

He describes it as a “transitional time” for rock music and movies.

Both he and his wife remain avid UCLA sports fans. They also share a taste for music from their college days.

“I’m a fountain of trivia on rock ’n’ roll,” he mentions. “Bruce Springsteen is number one, without a doubt. I’ve always liked Bob Dylan, Elton John, Eric Clapton, The Beatles and The Rolling Stones. I like the blues.”

Whenever Springsteen or the Stones perform in Los Angeles, the Pasternaks buy tickets to the concert.

By 1973, David Pasternak had graduated from UCLA and entered Loyola Law School of Los Angeles. He was on the law review there and worked hard.

“There isn’t anybody who really loves law school,” he says. “I enjoyed it. I worked hard. I took it very seriously because it was what I wanted to do, and I wanted to do well.”

At the time, he had the goal of becoming a corporate securities attorney and focused his attention on corporation and tax classes as opposed to litigation.

During the last half of law school, he secured a part-time job as a law clerk with Condon & Condon, a small firm in Santa Monica that focused on real estate litigation and probate trust work.

In his final semester, he became a student extern for Court of Appeal Justice Clarke E. Stephens (since deceased). Pasternak described the experience as his favorite class in law school.

He graduated from Loyola, cum laude, in 1976 and a few months later passed the State Bar exam.

Afterwards, he tried to obtain employment as a corporate securities attorney. Though he interviewed with numerous firms, there wasn’t much hiring going on in that area at the time. He applied for a position with the Securities and Exchange Commission, but was shut out due to a hiring freeze.

Eventually he landed his first job out of law school with the Department of Corporations, the state counterpart to the federal Securities Exchange Commission.

He says he was assigned to the enforcement division, “which put together cases for violations of California securities law,” noting: “That’s how I wound up in litigation.”

It would eventually prove to be a permanent change from his original career goal of becoming strictly a transactional attorney.

The Department of Corporations “was a good place to be,” Pasternak says, but adds: “I knew I didn’t want to be a career government attorney.”

Attorney General’s Office

Nonetheless, in 1979, his next job was with a government law office: the California Attorney General’s Office. His position was in its business and tax section.

There, he handled cases for the state commissioners of corporations, banking, savings and loan, real estate, and insurance. He also did work for the Franchise Tax Board and the Board of Equalization.

“I have always been sorry that I did not stay longer—it was a great place to work,” Pasternak says. “George Deukmejian was the attorney general. There were really good people in that department. It was a very difficult section to get into.”

|

|

|

Cynthia and David Pasternak attending a UCLA basketball game. |

While with the Attorney General’s Office, Pasternak was given responsibility for a case that stands out in his memory. He recounts:

“I was out of law school four or five years and Evelle Younger was on the other side of a case I was given in Orange County. He had been the attorney general only about a year earlier. Yet they let me handle the case. It was the kind of case where in private practice, a senior partner would have been arguing it.”

He says he was representing the California commissioner of insurance in a case involving a proposed merger, and prevailed in the appeals court.

Practicing in Century City

In 1980, Pasternak found himself an associate at the Century City firm of Tyre & Kamins. He would remain there for 13 years.

In 1982, Pasternak received a phone call from a former supervisor at the Department of Corporations that would lead him towards another major phase in his career. The Department of Corporations was taking over an escrow company, and Pasternak was asked if he would be interested in being a conservator of the company.

“I went and talked to the partner I was working for at the time and I said, ‘Listen I got this call, but I’m not really inclined to do it.’ And he said, ‘Absolutely! You ought to do it.’ So I called back and said I’d do it and got appointed.”

Weeks later, the conservatorship was converted to a receivership. It was Pasternak’s first step towards becoming one of the leading receivers in the state.

“In those days, in the Writs and Receivers Department, downtown, they had a list of approved receivers,” Pasternak explains. “So if you needed a receiver, you generally went and looked at the list that the courts had and you’d pick a name off.

“The way you got on the list was to get appointed as a receiver. So as a result of that one appointment, I got myself added to the list.”

The list was done away with in the early ’90s after judges concluded it was too exclusionary. However, by that time, Pasternak’s reputation as an effective receiver was firmly in place. His receivership experience began slowly in the ’80s, but quickly ramped up as he grew to like it more.

Numerous Receiverships

Over the last 20 years, receiverships have comprised the bulk of Pasternak’s practice. To date, he has acted as a receiver in several hundred cases. Pasternak himself has lost track of how many, but he roughly estimates “between 500 and 1,000.”

As receiver, he has overseen the day-to-day operations of properties and businesses of various sizes, ranging from small stores to multi-million-dollar empires. Pasternak points to a few particularly large cases over the past 12 to 13 years that stand out in his mind.

In 1998, he was appointed receiver of the One World Trade Center office tower in Long Beach, the tallest structure in that city. His appointment came as the result of a joint-venture dispute between the owners of the building. For approximately 10 months, Pasternak oversaw the operations of the multi-million-dollar tower until the parties eventually settled their dispute.

In December 2000, Pasternak was appointed by a San Bernardino judge to become receiver over a holding company for Wickes furniture in the Inland Empire, after its parent company built up a debt of approximately $80 million to a consortium of banks.

During his six-year receivership, Pasternak oversaw Wickes retail furniture and its sister-distribution company, becoming one of three of its board members. He eventually sold it for roughly $70 million. Pasternak says it was his largest sale of a property asset as a receiver.

In 2003, he was appointed receiver in a case brought by the Lehman Brothers investment bank involving two individuals who set up fake escrows and falsely obtained loans from Lehman Brothers and another bank for approximately $150 million.

The two were sent to federal prison, while Pasternak was given responsibility over approximately 100 properties throughout California and in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, in addition to other items such as high-end automobiles, fine wine, home and furnishings that he sold off.

His receivership in the Lehman Brothers case ended only about a year ago; the case had been stayed for several years due to the criminal proceedings associated with it.

As a measure of the amount of trust that Pasternak has built up over his career as a receiver, in 2005, the Office of Attorney General asked him to become receiver for the California Research and Assistance Fund, a multi-million dollar non-profit benefit corporation established through insurance company contributions after the Northridge earthquake.

Allegations had surfaced that former California Insurance Commissioner Chuck Quackenbush had used some of the fund’s monies for personal purposes, which jeopardized the organization’s non-profit status. Pasternak was asked to step in and help resolve the tax issues. He was able to do so—ensuring that funds from the organization went to California earthquake charities, rather than the IRS.

Sometimes, his receiverships turn out to be more complex than originally meets the eye. Pasternak was appointed receiver in February 2010 to take possession of stock certificates of two companies in a family law case. One company was a construction company, the other was a large, low-income housing developer.

While going through the company records as receiver, Pasternak came across evidence that the companies were engaged in apparent fraud by seemingly overbilling municipalities for construction through fake invoices. He alerted the judge, who sent him to the U.S. Attorney’s Office and the District Attorney’s Office. Shortly afterwards, the parties announced they were reconciling in order to attempt to rid themselves of Pasternak as a receiver.

The cities of Glendale and Los Angeles filed suits and the case was converted from a family law receivership to a civil receivership, which remains ongoing with several properties and tens of millions of dollars in the bank. The case has even taken Pasternak to India, where he filed suit in order to recover more than $30 million that was transferred from the receivership defendants to closely-held Indian companies to develop real estate in that country.

Pasternak recently was appointed as the receiver of the Gourmet Green Room, Inc., a medical marijuana dispensary in West Los Angeles that fell into receivership after a judgment was obtained against it by a lender.

Since December of 2012, Pasternak has effectively been operating the business of the dispensary.

“If you ever would have told me in law school, ‘You’re going to be doing this,’ I’d say, ‘Yeah, right!’ ” Pasternak says.

“I highly endorse their product by the way,” he adds, with an impish smile.

California Receivers Forum

In 1994, Pasternak and a group of his colleagues banded together and formed what is now the California Receivers Forum, an organization that began in Los Angeles and Orange County but has grown statewide. The purpose of the group is to professionalize the receivership practice, network, and educate the public about receiverships.

Pasternak says that most of the full-time receivers in the region know each other. He estimates there are about 20 full-time receivers in Southern California, with an even smaller group in the northern part of the state.

Peter Davidson is a partner with the firm of Ervin Cohen & Jessup, LLP, and a current co-chair of the California Receivers Forum. Like Pasternak, he has been a founding member of the organization. He speaks highly of Pasternak’s work in the area:

“He’s one of the top receivers in town. He has been doing it a long time and has had a lot of different cases. Big cases.

“Good receivers know what they are doing. They understand that they work for the court, not the parties. David Pasternak is who I would call a good receiver.”

Supreme Court Decision

One action by Pasternak as a receiver spawned a California Supreme Court opinion.

Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Lisa Hart Cole in 2005 appointed him as receiver in connection with real property in Santa Monica after its owner became the subject of a multi-count criminal complaint for various Health and Safety Code violations.

After weighing the costs of repair versus the costs of demolition, and the sale value of the the property with a building that was up to code standards as opposed to being a vacant lot, Pasternak petitioned the court for permission to raze the structure, arguing that there was a $150,000 advantage in taking that course.

Cole granted Pasternak’s petition over the objection of the owner, Guillermo Gonzalez.

The Court of Appeal for this district in 2006 affirmed, in an opinion by then-Presiding Justice Vaino Spencer (now retired), holding that “the court did not abuse its discretion in approving the less expensive and more profitable demolition and sale of the property over the more expensive and less profitable rehabilitation of the property.”

In a concurring and dissenting opinion, then Justice (now Presiding Justice) Robert Mallano argued:

“I agree with Gonzalez that it is his decision to forgo the $150,000 and keep his property. Only his financial interests are involved, not the city’s nor the courts’. If he wants $150,000 less, it is his decision to do so. The receiver would rehabilitate the property to make it safe and sanitary as required by law; the city should be happy as well. It is arbitrary and unreasonable to do otherwise in light of the inalienable right protecting property.”

The state high court granted review and, in 2008, in an opinion by Justice Marvin Baxter, held in City of Santa Monica v. Gonzalez, 43 Cal.4th 905, that Cole did not abuse her discretion in authorizing Pasternak “to contract for demolition upon finding that the property was uninhabitable and that rehabilitation was ‘not economically feasible.’ ”

Baxter questioned whether Gonzales had the means to finance the rehabilitation of the structure, pointing to his past failures to do so.

‘Making People Angry’

Since the receiver is only responsible to the court, it often puts him or her at odds with those who feel they have claims to a property and, like Gonzales, have different ideas as to what should be done with it. That Pasternak’s line of work can engender ill will is evidenced by a Google search of his name.

The third hit tells of a racketeering complaint filed in U.S. District Court against Pasternak and the Los Angeles Superior Court. The webpage to which the link leads declares:

“The complaint alleged that Attorney David Pasternak appeared in numerous cases as a ‘Receiver’ with no authority at all, as part of a pattern of operating receiverships at the court with no legal foundation, and thereby looting persons coming to the Court, where they expect honest court services.”

The rambling discourse also announces the likelihood that an “[i]nternational criminal indictment” will be filed against the Los Angeles Superior Court, as well as Judge Jacqueline Connor (since retired) “relative to the case of the Rampart FIPs (Falsely Imprisoned Persons).”

The sixth hit is a link to a “rip-off report” posted by one Andre Deloje of Santa Monica.

Pasternak had been appointed in 2009 as receiver in a dissolution of marriage case after Deloje failed to make spousal support payments. Pasternak sought and gained permission of Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Amy Pellman to sell two of Deloje’s undeveloped properties for $60,000 to satisfy both the spousal support order and the receivership fees.

Deloje rails:

“DAVID PASTERNAK ESQ. SOLD MY PROPERTY ON 12/07/2011, WORTH $300K+ FOR $60K,TO PAY HIMSELF FRAUDULENT LEGAL FEES OF $103,570.98 CLAIMED FOR ADMINISTERING A RECEIVERSHIP TO COLLECT $30K!... There should be no fees or compensation because the Receiver David J. Pasternak did not faithfully perform his duties. He did not collect one cent towards the divorce case.”

The facts are that Deloje appealed the order confirming the sale; the buyer refused to take title until Pasternak’s authority was resolved; the receivership continued; Deloje settled the dispute with his ex-spouse but he did not drop the appeal; the Court of Appeal in 2011 held, in an unpublished opinion by Presiding Justice Dennis Perluss of this district’s Div. Seven, that the properties could be sold to pay the receivership fees and costs. The sale took place.

Back in Superior Court, Judge Christine Hyde declined to grant fees to Pasternak in connection with the appeal. The Court of Appeal reversed, in an unpublished opinion issued last year.

The opinion, again by Perluss, says:

“The trial court denied Pasternak any fees in connection with the prior appeal, agreeing with Deloje that Pasternak should have ‘abandoned’ the appeal following the entry of judgment in the marital dissolution action. The court’s reasoning is flawed. Deloje was the appellant in this collateral receivership action, not Pasternak. To the extent the appeal could have been abandoned, it was Deloje who was in the position to do so and thereby permit the sale of the Crescent Drive properties to pay Pasternak’s receivership fee in accordance with the trial court’s order. He did not. By continuing to prosecute the appeal, Deloje prolonged the receivership, forcing Pasternak to incur costs to defend the appeal and complete the sale in accordance with the court’s order.”

Volunteer Work

Pasternak’s work in the courtroom and as a receiver is only part of what he undertakes. Throughout the decades, he has built up a sizeable list of accomplishments through his volunteer work with bar and charitable organizations.

In 1997, Pasternak served as president of the Los Angeles County Bar Association.

Having first become active in that organization around 1978, his involvement has spanned roughly 35 years. As a youth, he was president of the Barristers (young lawyers) in 1984-85; more recently, he chaired the Senior Lawyers Division (now a section) in 2008-09.

|

|

|

Greg, Kevin and Matthew, sons of Cynthia and David Pasternak. |

was on the Board of Trustees from 1983-85, 1989-91, and 1994-98, and has held membership on numerous other units, often chairing them. He says of LACBA:

“I still consider it my home.”

Pasternak says he enjoyed his tenure as president, despite the fact that it took up roughly one-third of his time that year.

During his term, he became determined to use his bully pulpit to help educate the legal community about the special needs and operations of the juvenile courts. Pasternak explains:

“As president of a local bar, you try and find an issue that resonates with you and that hasn’t been tackled by a recent president. For me, it was the juvenile courts.

“I felt they needed more attention. Lawyers and others needed more education about them.”

He formed a special committee featuring representatives from the various groups to help facilitate communication needed to improve the juvenile court system.

His volunteer work extends beyond LACBA, to a myriad of organizations throughout Southern California and beyond.

From 2003-04, he served as president of Bet Tzedek Legal Services, a non-profit organization that provides free legal services and advice to low-income and impoverished residents. He first became involved in the organization roughly 20 years ago when current Los Angeles City Attorney Mike Feuer was executive director. He remains on its board of directors.

“People tend to stay on the board,” Pasternak says. “It’s a wonderful organization. It’s our major personal charity.”

He notes that two of his children have volunteered there.

Since 2009, Pasternak has also served as a member of the California Access to Justice Commission, organized through the State Bar. He is currently working with the commission to help publicize the use of cy pres funds in class actions lawsuits to help fund legal services organizations that increase access of indigents to attorneys.

Pasternak has also served as a member of the State Bar MCLE Standing Committee, the Beverly Hills Bar Association Board of Governors, president of the Chancery Club, lawyer representative to Ninth Circuit Judicial Conference, member of the Judicial Council of California, and a California State co-chair of the American Bar Association Fellows. He has chaired various American Bar Association committees.

In August of 2012, Pasternak became the first person appointed by the California Supreme Court to the State Bar Board of Trustees (formerly the Board of Governors). His term as trustee began in October 2012 and continues until the conclusion of the annual board meeting in 2015.

Praise From Colleagues

“From day one on the Board of Trustees, David has shown great commitment to improving the profession and protecting the public,” State Bar President Luis J. Rodriguez says. The division chief in the Office of Los Angeles Public Defender adds:

“His many years of experience in law practice and many years of active involvement in bar related activities serve as a great foundation for his successful career as an attorney and as a community leader.”

The Board of Trustees is a place where “all of his talent and experience is much needed,” former LACBA president Harry L. Hathaway remarks.

Hathaway, who is of counsel to Norton Rose Fulbright, says he has observed Pasternak’s leadership in bar groups through the years, and reports:

“We were co-founders of the Senior Lawyers and Dave was instrumental in its success. I have worked with Dave in the ABA where he has distinguished himself in committee work and as a delegate to the House of Delegates representing the LA County Bar.”

Hathaway also notes:

“I have had the good fortune to have worked with him in major complex transactional matters. He is a keen strategist who knows how to close a deal.”

Also commenting both on Pasternak’s active involvement in bar activities and his excellence as a lawyer is Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Lee Smalley Edmon, a former LACBA president and her court’s immediate past presiding judge. She says:

“David is an outstanding leader of the legal profession. I have had the good fortune to work with him on a variety of bar association projects since we were both young lawyers—I won’t be specific about how long ago that was. We worked together in the Los Angeles County Bar Association—both in the Barristers Section and later in the ‘big’ bar—as well as the ABA. And most recently he has served as an excellent president of Chancery Club.

“From my years of working with David, I have a number of observations about him. He is a terrific lawyer—I have recruited him to serve as a contributing editor on the Weil & Brown Civil Procedure Before Trial practice guide. He is hard-working and reliable. When he takes on a project, he gets it done. But more than that, he gets it done well. He cares deeply about access to justice and has an uncanny knack for coming up with creative ways that the bar can serve the public and the courts. He is a man of great integrity and a dear friend.”

Edmon’s husband, Richard Burdge, who was last year’s LACBA president, comments:

“I cannot imagine anyone who has more selflessly served the profession, the organized bar and the justice system than David Pasternak. It seems like he has been the president or chair of virtually every organization he has been associated with, and he has done the hard work in committees whether in LACBA, the ABA, the Judicial Council or now the State Bar.”

Time Management

One might wonder where he finds time during the day to manage all of his commitments.

“He doesn’t have time for anything else,” a chuckling Cynthia Pasternak says.

“That’s a slight exaggeration,” David Pasternak counters. “But I try to balance it. Right now, there is a big time commitment with the Board of Trustees.”

He adds:

“Believe it or not, there are times when I have said ‘no’ to certain things.”

He notes that he was forced to turn down an ABA committee chairmanship on judicial independence simply because he was too busy with the office and other commitments.

Of all the myriad committees and activities he has been involved in over the years, Pasternak points to one that stands out for him: being co-chair of the Bicentennial of the Constitution Committee for LACBA during the late 1980s. In that capacity, he helped to produce a number of public service radio spots on the history of the Constitution that were recorded by actor Gregory Peck at the Capitol Records Building.

As Pasternak remembers it:

“We were all standing there, when all of sudden you hear Peck’s voice coming around the corner. Alan Rothenberg, president of the Constitutional Rights Foundation, was also with us as a co-sponsor, and it was ‘To Kill a Mockingbird’ that got him to go to law school….

“What was fascinating was watching [Peck] get ready to record the spots. Peck would read them and do various voice intonations as he was doing it, and he would ask us: ‘Gee, what does this word mean? Why do you have this word there?’ What was fascinating was that he wanted to understand exactly what he was saying so that he would say it right.”

Pasternak discloses that his real-life encounter with the on-screen Atticus Finch (the attorney portrayed by Peck in “To Kill a Mockingbird”) was “one of the most memorable experiences I’ve had as a lawyer.”

What advice would Pasternak give his own son who is currently in law school? Pasternak leans back in his chair and contemplates for a moment.

“Study hard…or I’ll vote on the Board of Trustees to make the bar exam harder,” he says.

Cynthia Pasternak

Cynthia Pasternak was born May 14, 1952 in Manhattan to Lillian and Joseph Rosen. Her family moved when she was 1½ years of age to the San Fernando Valley, where she has continued to live since then.

She grew up in a household with two younger brothers. Her father was a typewriter salesman, and later a commercial interior designer. Her mother was a homemaker who eventually went to work as a clerk for the Department of Public Social Services.

She attended Granada Hills High School, where she was an active and hard-working student, involved in many extra-curricular activities, including classical piano lessons from the time she was 6 until she completed high school.

|

|

|

|

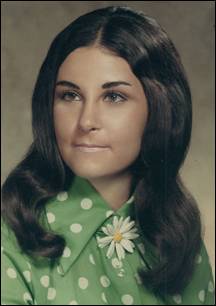

High school photo of Cynthia Pasternak (then Rosen). |

|

“I was very academic and active in the school,” Pasternak recalls. “I was drill team captain, in the girls’ honor group, a girl scout cheerleader in the girls’ athletic club. I was in everything. I was even the vice president of the French Club and I never had French. That’s because I went to a meeting every lunch period and every day after school because my friends were in it.”

In summarizing her childhood, Pasternak said she was “a real goody two-shoes in my day.”

Joining Mensa

At 16, Pasternak became a member of Mensa, an international society of persons with genius IQs.

“My father had a close friend who was in Mensa, and he told my father that he needed to take the test,” she explains. “My dad said, ‘I’ll only take it if my daughter takes it.’ So we both passed the home test, and we then went to UCLA to take the formal test.

“I didn’t realize that half-way through, my father had put his pencil down and stopped. But I took it, and passed—though I couldn’t imagine taking it again.”

From Medicine to Law

Unlike her husband, she didn’t have a firm fix on her career goals early on. While first attending UC Riverside, she settled on pre-med as a major.

In her junior year, she transferred to UCLA as a political science major, “never having had any political science,” Pasternak recalls.

The abrupt change in career focus came after Pasternak realized that she didn’t have the heart to deal with the circumstances that being a doctor would ultimately entail. She explains:

“I would have to deal with death and pain on a daily basis as a doctor. The thought of it just didn’t appeal to me.

“I wasn’t squeamish, but I couldn’t imagine having to tell a parent that their child is dying. That was just too hard for me and I told myself that I needed to do something else.”

After the decision to get out of medicine, law school seemed to be the best default choice for her.

She applied to law school “at the last minute,” as she described it, and enrolled in Loyola in 1973.

While prepping for law school during the summer, Pasternak became a student intern at the California Youth Authority in Sacramento. After her first year of law school, she was asked back to be a graduate student assistant with the program, where she did research and development and wrote articles regarding diversionary programs.

Her hard work continued into her time at law school, where she studied diligently and served as the Ninth Circuit Editor for the law review.

“I worked like a dog—I was tired and burnt-out,” Pasternak says, matter-of-factly. “I don’t know that I loved law school, but I don’t give up. I never give up.”

A Young Attorney

Cynthia Pasternak graduated from law school in 1976, and soon found herself working as a law clerk in the office of Edward L. Masry. Masry was the attorney who would eventually gain notoriety in the Erin Brockovich action against Pacific Gas and Electric over groundwater contamination. In his office, Pasternak found a challenging working environment.

“When I became a lawyer, they still treated me like a clerk,” Pasternak recalls. “I stayed there because I was the ‘girl’ in the office. In those days, even Sandra Day O’Connor was a legal secretary.

“I got responsibility as an attorney, but since I had been the clerk, they still had me go get the Rams tickets on Fridays and similar duties.”

She rarely saw Masry, whom she described as being a “business getter” who was often out of the office. Though she struggled to be taken seriously as an attorney, she credits an attorney in that office, Andrew Zanger, for mentoring her and showing her the ropes of the legal profession in her first job outside of law school.

While she described her years in Masry’s office as “a quick experience” that she “moved on from,” Pasternak still recalls some memorable cases that she handled while at the firm. For instance, a client named Raymond Joseph Teller walked into her office, asking that he have his name legally changed.

He is now known simply and legally as Teller, the silent half of magic’s “Penn & Teller.”

Other cases from her Masry days included representing local politicians, the Church of Scientology, as well as numerous members of the L.A. Rams in business, divorce and other matters.

Overall, Pasternak described herself in those days as a “young, naive, newly-married kid.” Not wanting to settle for what the law office of Edward Masry offered her, in 1978, she decided to look for something else in an area of town she wanted to work in: Century City.

She developed a unique job-searching strategy. She picked out a building she wanted to work in on Century Park East, parked her car across the street, then started peppering offices in the building with her resume, starting on the top floor and working her way down.

“I started on the 22nd floor,” Pasternak recites.

By the time she got to the 21st floor, someone who was impressed by her directed her to an office on the 19th floor, suggesting: “Why don’t you go down there are meet the partners?”

As it turns out, the partners were with the firm of Irwin, Hale and Jacobs. Pasternak says they all “hit it off,” and she started a 12-year association with the firm based on what was effectively a cold call for employment.

Variety of Cases

At that firm, Pasternak managed to expand her experience across a broad spectrum of law.

“It was a general law firm,” she says. “And being the ‘girl,’ I got everything that walked in the door there. I did family law, conservatorships, a lot of personal injury product liability on both sides, plane crashes, real estate, you name it.”

She threw herself into a wide variety of cases, including motor vehicle accidents, product and premises liability cases, dog bites, mold cases, aircraft assembly, government entity cases, and everything else in between.

Despite all the new areas of law she had tackled, Pasternak declares that “[i]t wasn’t intimidating,” saying: “I found it interesting, because I had always been interested in everything.”

While at Irwin, Hale & Jacobs, Pasternak took on what she describes as one of the most interesting cases of her litigation career when she represented a large group of family survivors of a Mormon couple who were killed when they flew a private Cessna airplane through a chain-linked fence. Each of them had children by previous marriages and they had additional children through their own marriage. On top of that, the family had adopted numerous other children to add to their clan.

“They had so many kids,” Pasternak recalls. “But the interests of the kids had differed among them.”

She represented half of the dozen child-survivors to help sort out various issues of the estate. Attorney and aviation specialist Ned Good represented the other six children.

Good was so impressed with Pasternak in that case that he named her the “Baby-Faced Assassin.” It was a nickname that stuck with her throughout her tenure at Irwin, Hale & Jacobs.

|

|

|

|

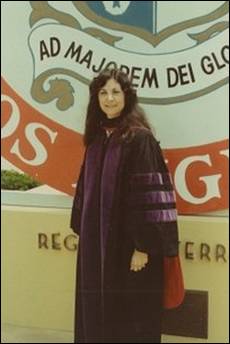

Loyola Law School graduate Cynthia Pasternak. |

|

Pasternak recalls driving to Blythe, a rustic city in Riverside County, for depositions in that case. She says she was “wearing my light-turquoise three-piece skirt-suit, in heels.”

She was soon to feel out of place. Pasternak brings to mind:

“I pulled into a market and had to ask if there was a two-story building in town somewhere. I was directed to the Holiday Inn on the other street.

“Well sure enough, Ned Good was there in a motel room with jeans on, sitting on the bed. That’s where the deposition was.”

Striving for Balance

To help find her balance between work and her growing family, Pasternak left her position with Irwin, Hale & Jacobs in 1990, and immediately opened up her own firm, the Offices of Cynthia F. Pasternak. At this time, she also served as of counsel to the employment law firm of Herman & Wallach, all the while keeping up with a myriad of bar activities.

It is an impressive juggling act that Pasternak has somehow managed ever since.

Still, she found the first year on her own as an attorney to be daunting.

“At the end of that first year, I had a six-week jury trial in Bakersfield while my son was still an infant,” Pasternak says. “I couldn’t use the secretary with Herman & Wallach. The only time I used their secretary was to sign proofs of service and put them in the mailbox. Other than that, I typed and stamped every document. I did everything myself that first year.”

She ended up winning the case, but even that victory didn’t mean a letup in the work.

The case was initially brought by a would-be buyer of real property against defaulting sellers, seeking specific performance. However, the buyer dropped his action after the real estate market collapsed, and the action that went to trial was on a cross-complaint brought by the sellers against the real estate agents, represented by Pasternak. Under a provision in the sales contract, the sellers were liable for the prevailing parties’ attorney fees.

“The day I got the verdict,” Pasternak says, “the plaintiffs fraudulently conveyed property that was the only asset that they had. I ended up having to pursue the fraudulent conveyance action because the defendant wouldn’t do it, and ended up owning the property.”

Her self-assessment is:

“I don’t give up. I’m a bulldog.”

She says her tenacity has served her well as a mediator.

“If we can’t settle it at first, I find out what’s missing and we will settle it the next time,” she says.

Pasternak found that even a bulldog needs rest now and again. Her work schedule the first year on her own took a toll.

“I realized I was going crazy doing all this work,” Pasternak says, commenting:

“Eventually you need to sleep.”

During the second year as a sole practitioner, she decided to hire a law clerk, Heather Appleton, who became an associate in 1992 after passing the bar exam. With other personnel on board, she was able to successfully develop her practice.

A Family Firm

By 1993, her husband was ready to join her and form their own firm.

“Dave was envious of what I was doing on my own,” she says. “He asked Pete Appleton to join in, and we started a firm together.”

Peter Appleton, father of Heather Appleton, was at the time, like David Pasternak, a partner in Tyre & Kamins. Terry Cohn, a newer attorney there, also joined the endeavor, and the firm of Appleton, Pasternak and Cohn was born. There were actually two Pasternaks in the firm, but the thought was that stating the name twice would be redundant. Cynthia Pasternak became the managing partner, and also became, for the third time, a mother.

The firm evolved into Pasternak, Pasternak & Patton, later assuming its present moniker.

Litigator to Mediator

In the early years of her firm, Cynthia Pasternak concentrated on employment law, personal injury, real estate and business cases. Once she partnered with her husband, Pasternak began to transition from litigation into mediation, which she now does full time.

For Pasternak, it was a natural transition that made sense for her.

“I always loved to negotiate,” she says. “I settled most of my cases and didn’t go to trial very often.

“I didn’t like the fuss of litigation. I like getting things done.

“So I started taking classes in ADR long before it was fashionable.”

Though she initially entertained the idea of juggling both litigation and mediation work, she soon decided that devoting herself full-time to her mediation practice was the better course for her.

“I realized that I couldn’t litigate one day, and then mediate for somebody the next day,” she says. “You have conflicts.

“If there’s an employment case and I deal with you one day trying to settle your case, but the next day I’m suing you, people wouldn’t be comfortable with that. I found that kind of conflict in a lot my cases.”

She began with the ADR program set up through the courts, then moved on to party-pay panels. Through word of mouth and many successes, she has built up a reputation as one of the best respected mediators in the region.

On two occasions, 2003 and 2008, the Los Angeles Superior Court conferred on Pasternak its ADR “Case of the Year” award.

The 2003 case involved the daughter of a family who had contacted the cemetery where her father had been buried years earlier. Without the knowledge or permission of her family members, she persuaded the cemetery to have the body disinterred from the family plot and cremated. When they learned what had happened, the other family members became distraught.

Part of their objections stemmed from their religious beliefs against cremation. The husband’s widow proclaimed that she now felt that she would be prevented from being truly reunited with her spouse when she was laid to rest.

|

|

|

|

Cynthia Pasternak at a Jewish temple while on a trip to Cuba with the Beverly Hills Bar Association. |

|

For Pasternak, the question presented was: “How do we compensate for eternity?”

What at first seemed to be an utterly intractable problem became solved under Pasternak’s persistence and creative thinking. By the end of the mediation, the family plot burial site had been upgraded to a crypt for two in their church behind the altar. That burial site was considered a place of great honor that the family would not have otherwise been able to afford.

The widow wept with joy when Pasternak presented her with the settlement offer.

In 2008, Pasternak was confronted with another challenge that seemed unsolvable at first glance.

The case began after a disabled couple in their 90s had sued their landlord/property owner for retaliatory eviction from their duplex after they had complained about a slip-and-fall incident.

The couple expressed a wish to simply live out their final years in dignity, rather than having to rely on their relatives for a roof over their heads. However, both sides were proving intractable in terms of settlement demands.

Instead of pressing for a large settlement amount, Pasternak got the sides to agree that the couple would be set up in new housing that would be rent-free for life. The couple was more than satisfied with this arrangement, and when the defendant considered the numbers, concluded it was far more agreeable than the initial demands presented.

For Pasternak, the case embodied the popular phrase “win-win,” which is what she says she strives to achieve in every case.

“I listen to people, and I try to give them what they want,” Pasternak says in summarizing her mediation work.

Compared to her previous litigation work, Pasternak says there is no contest in what has been more enjoyable for her. She asks, rhetorically:

“Who loves discovery? Who loves doing paperwork? Form interrogatories?”

Pasternak responds to her own query: “That’s garbage as far as I’m concerned.”

For Pasternak, mediation has proven not only rewarding, but constantly interesting. She can point to any number of eyebrow-raising cases, such as the time she was called in to mediate a sexual harassment case where a sushi chef was alleged to have created a phallus and other sexual items that he placed in a paper bag and gave to a waitress.

Volunteer Work

Much like her husband, Cynthia Pasternak’s legal career is not confined to the office.

Her activities include membership on a special ADR advisory board for the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California, an ADR “Top Achiever” award from the Los Angeles Superior Court, recognition as an American Bar Association fellow, membership on the Executive Committee of the American Bar Association Metropolitan Bar Caucus, being a member of the ABA House of Delegates, volunteering with Bet Tzedek Legal Services and the Public Counsel Law Center, and being recipient of the Beverly Hills Bar Association’s Distinguished Service Award as well as its Executive Director’s Award.

Her association with the Beverly Hills Bar Association has remained particularly strong. In 2005, she began a one-year term as its president. During her tenure, she emphasized issues surrounding balancing work with one’s home life.

It has remained a passionate issue for her, having written about and lectured on the subject in various forums.

Marc L. Sallus, another past president of the BHBA, who worked with Pasternak in that association and others, says of her:

“Cynthia has amazing amount of energy. When you combine it with her vision and drive, incredible things occur.

“I have been blessed working with her over the years on so many bar projects. One of her outstanding programs was to focus on family lives and the practice of law. It has helped all of us to rethink the practice of law.”

Marc Staenberg is the executive director of the BHBA, a position he has held for 10 years. He has a one-word description in summarizing Pasternak and her contributions to the organization: “Dynamic.”

He says Pasternak’s efforts for the association and the larger legal community have been tireless.

“She is extremely hard working,” Staenberg says. “She has both the left brain and right brain working. She is both super creative and well organized.

“Work-life balance was the issue of the time and she managed to organize and execute a great symposium on the subject.”

The symposium took place in April 2006 at Pepperdine Law School. Among the speakers were then-Pepperdine University School of Law Dean Kenneth Starr, prominent law professors, attorneys, doctors, politicians, Pasternak herself, as well as a keynote address from “Ally McBeal” star Calista Flockhart who was juggling her own work-life issues at the time.

Pasternak has continued to provide her leadership skills to the Beverly Hills Bar Association, having recently launched its Senior Lawyers Group.

Lucie Barron, president of ADR Services, Inc., tells why her firm was delighted to add Pasternak to its panel:

“Cynthia has been one of the pioneers in the mediation profession, has been doing this for over 20 years and is very experienced and polished. She had a reputation for great determination and tenacity, insight and an ability to understand the seemingly intractable issues which hinder dispute resolution. She is confident in getting a difficult matter resolved and she does.”

Her Own Balance

Pasternak remains reflective when she thinks about how she faced her own challenges in balancing work and life priorities. When having to prioritize her responsibilities, Pasternak says it’s no contest as to what comes first, declaring:

“My kids always have been, and always will be, my number one priority. You have to prioritize, and I did not miss a school function. I was active in their schools to the extent that I could be.”

Even with clear priorities in mind, Pasternak cautions others to try to remain adaptable.

“Things will go wrong,” she says. “You need to be flexible in your priorities and regroup.”

She cites the days when she ran her own firm as an example.

“I always hated billing,” she says. “But the night before I would go to work, I would allocate a certain amount of time to each project that I had to do during the day. If I reached that time, I would stop and put it away. Because if I didn’t, I would just keep going on.

“Somebody had to pick up my kid at the end of the day, and it was always me. I had to budget my time in five-minute increments.”

Pasternak says she sometimes wonders how she has managed to do it all.

“Three kids is insane,” she acknowledges, in the context of attempting to juggle motherhood with a career, observing:

“One is doable. Two is OK if you have a girl, because they will help. But I had three sons, and a husband. I even had a male dog.

“But I did it.”

Copyright 2014, Metropolitan News Company