Wednesday, October 29, 2014

Page 6

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

Remember That Honorary Badge We Gave You? We Want It Back—Sheriff Pitchess

By ROGER M. GRACE

Seventh in a Series

“Sheriff Peter J. Pitchess announced today he is recalling all badges which have been issued by his department to persons not directly concerned with law enforcement work,” a July 3, 1963 article in the Herald Examiner reports, adding:

“More than 4700 badges must be returned….”

The bulk of those badges had been bestowed by the previous sheriff, Eugene Biscailuz, during his 26-year tenure; some had been given out by Pitchess, himself, after taking office on Dec. 1, 1958.

“His action, Pitchess explained, is based on numerous court decisions and the legal advice of the Los Angeles County counsel,” the article relates.

Another reason put forth by Pitchess is reflected in the next morning’s issue of the Los Angeles Times. It quotes him as saying:

“Historically, reputable people from all walks of life [have been] called up to assist a handful of regular officers when occasion demanded it under the rule of posse comitatus.”

But now, “the complexities of modern-day society require persons enforcing the law to possess knowledge, training and skills far beyond the requirements of the past,” Pitchess said, according to the Times’ account.

|

|

|

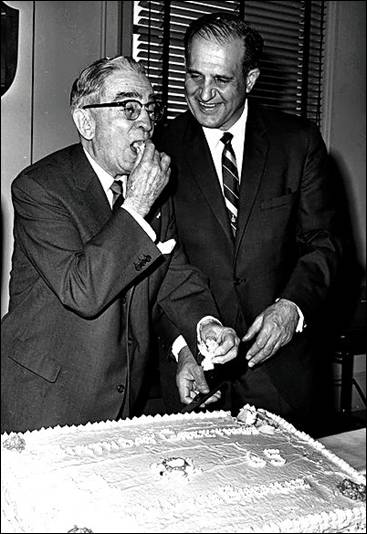

Los Angeles Times Photographic Archive, UCLA Library

Los Angeles County Sheriff Pete Pitchess, right, watches as retired sheriff Eugene Biscailuz observes his 82nd birthday by sampling cake during a party March 13, 1965 at the sheriff’s office. |

The fact that it was no longer necessary to form posses—a power that still existed then, and does even now—bore no relationship to the decision to stop awarding honorary deputy badges and to try to retrieve those already conferred. Pitchess, and Biscailuz before him, did not give out the honorary badges to those they had just inducted in a posse…they gave out metallic remembrances, no conditions attached, for sake of goodwill.

![]()

Pitchess’ explanation as to why the honorary sheriff’s badges had been issued was on a par with the 1938 rationalization by Los Angeles Chief of Police James E. Davis for the 7,843 LAPD honorary badges that were outstanding. Davis, as noted in a recent column, argued that the city needed an auxiliary force that could be called up in times of emergency. Yet, recipients of the city badges had received no police training; they met no particular qualifications.

It was the same with honorary deputy sheriff badges. We’re not talking about badges given to reserve deputies, who undergo many hours of training—there was a 20-week nighttime training program, according to a Jan 7, 1962 Times article—and valiantly undertake the periodic performance of law enforcement duties, as volunteers. We’re talking about a souvenir presented by the sheriff to whomever he pleased, akin to a “key to the city” given out by a mayor.

Among those accorded an honorary Los Angeles police badge in the 1930s was child star Shirley Temple. Would Chief Davis have actually been prone to summon the curly topped moppet to help defend the city in a time of emergency? Despite her charms, it is doubtful she would have been able to quell a riot by bursting into a chorus of “The Good Ship Lollipop.”

Who were some of the folk on whom Pitchess had bestowed honorary badges? According to news reports of the time, they included the likes of Los Angeles Mayor Norris Poulson; Greece’s Crown Prince Constantine; Fred Hayman, resident manager of the Beverly Hilton; and Eugenia Clair Smith, a Reno, Nev. philanthropist.

Would Pitchess actually have expected Poulson to depart his City Hall office, or abandon a 1961 reelection fundraiser, to assist sheriff’s deputies in making arrests?

How would Constantine, who received his honorary badge in 1959, have reacted to a transatlantic phone call from Pitchess along these lines?:

“Hey Con, remember me, Sheriff Pete? Listen, boy, we need you now. Hop on a jet and report to me—we’re going up into the hills to hunt down some bad guys.”

Hayman, at the time he received his honorary badge early in 1962, was, on the side, a principal in a fledgling operation on Rodeo Drive, Giorgio of Beverly Hills. This was the first luxury boutique on the street, soon a success, beckoning similar operations to the now-renowned lane. And if Pitchess had phoned to ask Hayman to divest his attention from notables being attracted to his shop, what would you imagine the response would have been?

Smith was, when awarded her star, aging—evident from the photo of her in the Dec. 4, 1958 issue of the Times in which the gift by Pitchess is announced. A 1970 published Court of Appeal decision tells us that Smith was “elderly” and her estate was subject to a conservatorship. The Pasadena Star News, in its issue of Sept. 26, 1972, reports that a Los Angeles Superior Court commissioner had approved the sale of the conservatee’s Bel Air home to singer Dean Martin, and notes her age was 89.

So, when Pitchess presented her with an honorary badge at a Press Club event—at a time when she was in her mid-70s—was it conceivable that he might be phoning her sometime asking that she excuse herself from a charity tea in Reno, come to Los Angeles County, strap on a pistol, and help make some arrests in Lennox or Newhall?

Oh, and there’s another reason why it could not have been supposed that by accepting an honorary badge, Smith was impliedly inducted into a posse. While the duty to join a posse, when summoned, now devolves upon “[e]very able-bodied person above 18 years of age,” the duty was, until 1976, restricted to “[e]very male person above 18 years of age.”

![]()

A July 10, 1963 Paul Coates column in the Times laments:

[T]he law out here, way west of the Pecos, is breaking down.

All us deputies who have voluntarily been vigilant in this town have been told to turn in our stars.

Peter Pitchess, Sheriff, has gone and posted notice that he is calling in all the ‘Honorary’ badges issued to such stalwart riders of the purple sage as producers, movie stars, prominent press agents, discount house operators, furniture manufacturers, yachtsmen of some note, cloak-and-suiters, and, regretfully, newspapermen.

And I don’t like it. When that boy, Peter, first rode into town, I said to folks: ‘Give ’im a chance. He’s tol’able.’

Now he’s trying to take over. And I say it’s wrong. Why, some of them men been deputized since Ciro’s first opened [in 1940, closing in 1957]. They’s even a few bow-legged, badge-bearing hombres remembers way back to the old days of the Clover Club [1931-38].

Coates, who appeared nightly on KTTV, mentions in the column that he was never ostentatious in displaying his long-held badge, which he kept nestled in his wallet, but allows that he would “kind of casually let people see it when I was paying a bill or identifying myself to backward citizens who don’t look at television.”

|

|

|

COATES |

The columnist vows: “[T]omorrow I turn in my badge.”

Why Coates, and others, would relinquish their personal property—lawfully bestowed gifts—simply because a county official made a sweeping request for the surrender of such possessions, is beyond my ken.

Giving away deputy sheriff’s badges to those who were not actually deputy sheriffs should never have occurred. It vested in donees of such badges the means of projecting the image of an actual law enforcement officers, sometimes leading to mischief, occasionally fraud.

An appropriate remedy would have been to cease awarding honorary badges—unless, by virtue of size, shape, and wording, it would be unmistakable that they were not actual deputies’ stars—and to do what the LAPD had done at various junctures in the past, as previously noted here: render existing honorary badges obsolete by issuing new and distinctive departmental badges.

Instead, Pitchess did something, also undertaken in the past by the LAPD: he called upon honorary badge-holders to forfeit a belonging without compensation. Many, obsequiously, complied.

![]()

Here are some other press reactions at the time of the badge-recall:

•A Van Nuys News column of July 19, 1963, by Les Claypool notes that Pitchess “has got around to asking for all those honorary sheriff’s badges including those used as press badges, to be turned in,” commenting:

“Good idea but it’s a little late.”

He notes that the LAPD had taken that step long before.

“When [Mayor] Frank Shaw went out and Fletcher Bowron came in [in a 1938 recall election], all outstanding badges were nullified,” he recounts.

“Many never were returned and I suppose they are souvenirs now,” Claypool’s column continues. “But Los Angeles changed the shape of its police badges and I don’t believe that any one on earth has one of the present day badges unless he is a police officer it and entitled to it.

“That’s how it should be.”

•Harold Hefferman’s Aug. 10 syndicated column, datelined “Hollywood,” remarks:

“Dating back to the high-spending, anything-goes days of the movies, it’s been the customary practice for law enforcing agencies to hand out the awesome credentials to stars, producers, directors, even a few rug merchants or discount store operators.

“When those so honored get themselves involved in a night club brawl or a freeway accident, the simple procedure is to dig into their wallets and flash that official badge.

“So many messy and embarrassing situations have been erupting lately, however, that [Sheriff’s Department personnel] finally are forced to call in outstanding credentials and abolish the practice entirely.”

![]()

“Hold on!” the Board of Supervisors hollered. What if they, the county’s governing body, wanted to have some of these badges returned to the donees? Wasn’t that their prerogative?

The Aug, 7, 1963 issue of the Times, telling of the previous day’s board meeting, says the supervisors also questioned whether the sheriff’s action contravened “the interests of national defense.” The article relates:

“Chairman Warren Dorn said that guards and special agents for railways, aircraft and other defense plants are concerned over the revocation and the crippling of their power to make civilian arrests in emergencies.”

Dorn, the article continues, “said he feels that” the news media “need identification in emergency situations.”

County Counsel Harold W. Kennedy was asked to report on these issues. A response came on Sept. 6 in a memorandum by Deputy County Counsel Irvin Taplin Jr.

No, supervisors could not countermand any particular badge revocation, the memo indicates.

One section “of the Badge Ordinance gives the Sheriff the authority relating to the issuance and control of the badges bearing the title ‘Deputy Sheriff’ ” and other sections “provide the Sheriff may issue such badges,” Taplin writes, concluding that “the decision to issue or revoke these badges rests in the sound discretion of Sheriff Pitchess.”

The action by Pitchess, Taplin points out, “has no effect upon…those badges issued licensed private patrolmen pursuant to the County License Ordinance….”

Honorary badges were, like genuine sheriff’s deputies’ badges, gold-colored stars; those of private security guards were silver-colored shields.

While some journalists, like Coates, had been awarded honorary badges, they were not used for the purpose of identifying the bearer as a member of the press. Taplin explains:

“All legitimate members of the press and other news media are issued official ‘press passes’ by the Sheriff, Los Angeles Police Department, California Highway Patrol, and other law enforcement agencies in this County, In the event of emergencies, disasters or events of public interest requiring the presence of the press, they are identified and admitted to the scene by reason of their press pass rather than the possession of an honorary badge.”

The memo recites:

“On October 29, 1962, we advised the Sheriff that under certain circumstances, he could be held liable both personally and on his official bond for the actions of the possessors of his honorary deputies badges.”

(The 1962 opinion is not among those in a bound volume at the Los Angeles County Law Library, and the Office of County Counsel has been able to locate it. Senior Assistant County Counsel Roger H. Granbo explains that the advice to Pitchess “could have been given in any number of ways, but it appears that it was not given in a formal County Counsel opinion.”)

What appears to be the primary motivation behind Pitchess’ call for the return of honorary badges is the avoidance of personal liability. An attorney himself, he was obviously not inclined to draw attention to his own vulnerability to legal actions brought by persons defrauded or otherwise harmed by culprits posing as a sheriff’s deputies.

Thus came his fib that the recall was tied to posses becoming obsolete.

An opinion by Deputy County Counsel Robert C. Lynch, sent to Chief Administrative Officer Lindon S. Hollinger on April 17, 1962, warns that the county could incur liability based on conduct of employees who are not peace officers sporting badges with the words, “Deputy Sheriff.” A March 28, 1963 Long Beach Press Telegram article notes that such badges were worn by the likes of “investigators in the offices of the auditor, health department, Superior Court and public defender; by Superior Court clerks, by deputy poundmasters and by guards at many county facilities.” On April 9, 1963, the board voted to remove the words “Deputy Sheriff” from the badges of those who weren’t.

![]()

![]()

![]()

FOOTNOTE: In its webpage on Pitchess, Wikipedia says that “[d]uring his 23 years as sheriff, he eliminated the county’s informal posse comitatus.” This is apparently derived from an error in the Los Angeles Times’ April 5, 1999 obituary of Pitchess.

The Times article recites that Pitchess, within two weeks of assuming his department’s top post, “accepted a saddle from the Sheriff’s Silver Mounted Posse.”

It goes on to say:

“To begin professionalizing the department, Pitchess called in all the hundreds of special deputy sheriff badges in the hands of celebrities, members of the media and political activists, and officially disbanded the county’s informal posse.”

The Sheriff’s Silver Mounted Posse, which was seen each year in the Rose Parade, was formed in 1933 and was the genesis of the Sheriff’s Reserve. Pitchess merely observed in 1963 that resort was no longer being made to the power to summon a posse comitatus—that is, a group of men conscripted on an ad hoc basis. (The words are Latin for “force of the county.”) He did not act to disband the long-standing cadre of reserve deputies who fancifully employed the term “posse.”

|

|

|

Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department

Sheriff’s Mounted Posse has not been disbanded, contrary to reports. |

An article in the July 29, 1969 issue of the Van Nuys News and Green Sheet says of the Mounted Posse:

“Classified as deputy sheriff reserves, posse members are required to be on call 24 hours a day to assist in emergency and disaster situations….

“Principally, they are called out to search for and rescue persons lost in mountainous areas and to round up stock endangered by brush fires.”

The group is now comprised of citizens who act helpfully, but are not necessarily part of the reserve.

Copyright 2014, Metropolitan News Company