Thursday, October 9, 2014

Page 6

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

Sheriff Eugene Biscailuz Bestows Thousands of Honorary Deputy Badges

By ROGER M. GRACE

Sixth in a series

Issuance of honorary City of Los Angeles police badges—which gave the appearance of official emblems and thus conferred on recipients advantages enjoyed by actual officers, such as being extended credit—pretty much came to a halt in 1938 when the Mayor Frank Shaw was recalled and Judge Fletcher Bowron replaced him….but the practice continued at the county level for another two decades.

Eugene Biscailuz was sheriff from 1932-58. Though a principled and accomplished office-holder, he persisted in disseminating look-alike deputy sheriff stars, heedless of the mischief done by some holders of such badges.

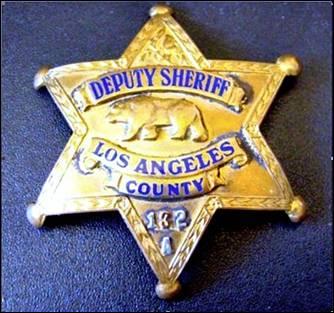

He “gave out thousands,” badge collector and retired LAPD commander Keith Bushey, says. Bushey supplies the example of what has come to be known as the “Biscailuz Badge,” at right.

At the bottom is the letter “A.” The letter has no particular significance except to differentiate the badge from one worn by actual officers.

![]()

Ironically, this giver of badges had once played the role of a taker of them. While William I. Traeger was sheriff, and Biscailuz was undersheriff, the latter was put in charge of gathering up “special” badges that had been provided to private security guards.

A public statement by Biscailuz was published in the Dec. 15, 1923 edition of the Los Angeles Times.

“The Sheriff’s office has been making a survey of the appointments of special deputy sheriffs who have been sworn in for corporations to act as guards and in other confidential capacities,” it begins.

I remember the old westerns in which the bad guy has escaped and the sheriff bellows out, “I’m deputizing every last one of you men—we’ll git that varmit.” I hadn’t known that the sheriff, in past times, deputized night watchmen.

Biscailuz’s statement continues:

“Letters have been written to the different corporations concerning these men but in a great many instances the men who have been deputised at the request of the corporations have left their employ and are still wearing the badges that should been turned into the Sheriffs office at the time of the termination of their employment,”

He says that only half of the private firms to which letters had been sent responded, and warns that if they don’t send a letter of acknowledgement, their security personnel will lose their badges.

The undersheriff directs the holders of the badges to report in, if they hadn’t done so recently, and admonishes those who received badges from prior administrations that if they wear the emblems, they are “subject to prosecution for impersonating an officer.”

Biscailuz left the post of undersheriff in 1929 to organize the California Highway Patrol, serving as its superintendant; returned to his old job in 1931, and was appointed sheriff by the Board of Supervisors in 1932 after Traeger was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives.

(Traeger and Biscailuz both held law degrees from USC; Biscailuz’s successor, Peter Pitchess, had one from the University of Utah.)

![]()

Once he ascended to the office of sheriff, Biscailuz became known for his largesse in giving out honorary badges.

Badges went to those who had helped Biscailuz…or might help him…or just to people who wanted them.

|

|

A 1929 California Supreme Court opinion alludes to a man who “was a regularly employed janitor at the Los Angeles county courthouse, and a deputy sheriff, under due appointment” who “had on his person a regularly numbered deputy sheriff’s badge.”

The value of the metallic stars far exceeded the cost of materials and labor. An article in the December 1999 issue of Los Angeles Magazine remarks:

“These ‘juice badges’ conferred clout and cachet.”

The words “Honorary Deputy Sheriff” appeared in resumes of those holding the badges, as well as in their obituaries.

In contrast to the custom of his successors, Biscailuz’s badges did not automatically go to local officeholders. A Jan. 16, 1958 article in the Long Beach Press Telegram reports that Biscailuz had bestowed badges on all five members of the Lakewood City Council and the city administrator, noting:

“It’s the first time [the] sheriff has given official badges to city officials.”

![]()

It was remarkable that Biscailuz eluded criticism for his serial badge-giving. He was engaging in the very activity that had periodically sparked tempests in the City of L.A., before the practice was halted.

In fact, bestowing too many badges was a minor factor in the downfall of a Los Angeles sheriff, John C. Cline, who headed the department from 1915-21. What he gave out, in large numbers, were not “honorary badges,” such as those conferred by Biscailuz, but “special” badges—that is, those worn by private security personnel, who possessed a semblance of law enforcement authority.

Yet, some of the persons receiving such badges had no connection with security operations.

For example, one recipient of a special deputy’s badge was silent film star Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle. His manager, Lou Anger, also got one. A Times article of April 9, 1918, reports that the duo came to see Cline one day, with Arbuckle complaining that he had been robbed on six occasions in the past three weeks by highwaymen on Long Beach Boulevard.

“Sheriff Cline immediately swore in as special deputy sheriffs both Arbuckle and his manager,” the article says.

According to the Times, “They climbed into the big blue touring car, each with a shining badge denoting authority.” An April 27 account in the Morning Oregonian, published in Portland, contains contrary information. It says that the two received guns from Cline and that “Roscoe was going to get a nice silver badge,” but that Anger insisted, “Those rough neck hold-up men would steal anything, and if they find out you have a silver badge they raill be laying for you,” resulting in Arbuckle declining the badge.

Whichever version is true, it appears that Cline did bestow more of the special badges than there were private security guards in need of them.

A Jan 6, 1920 Times article tells of actions taken by the Board of Supervisors to rein Cline in, including a decree that special badges given out by him be returned.

The article relates:

“The alleged promiscuous issuance of deputy badges by the Sheriff has for some time been a bone of contention. It was declared that 8643 special deputy badges have been given out, although legally the Sheriff can issue only 100. New badges of a special design will be secured by the county purchasing agent and they will be issued by Clerk [A. M.] McPherron on application approved by the Supervisors. Only these badges will be recognized….”

A Jan. 8 article in that newspaper quotes Cline as saying that he understood that the supervisors were going to act to limit the number of special badges to 200, protesting, “The shipyards alone use almost that number,” and adding:

“Other requests for such deputies have come from the Supervisors, the road deparrtment, State Highway Commission, the Board of Education, newspapers. hotels and other industries. To thus limit the appointment would give blackguards, thieves and thugs full sway.”

(Cline wound up losing his job in 1921, through the mechanism of the Board of Supervisors’ chairman, on instruction of the board, filing an “accusation” in the Superior Court, with the judge upholding the allegations of misfeasance.)

Despite outcries in the past over the awarding of badges to non-law enforcement officers, the congenial and much-liked sheriff, who rode horseback in parades and never had serious election opposition, stirred no controversy. The propriety of his issuance of honorary badges came into question only after he left office.

![]()

“His friendliness, his eagerness to do you a favor, and his insistence on sharing with you the perogatives of his office are heartening,” L.D. Hotkiss says of Biscailuz in the Aug 25, 1948 issue of the Times.

He continues:

It was this eagerness of Gene to pin honorary deputy sheriff badges on all good Joes which nearly threw him once.

An Allied court was trying a bunch of alleged minor league Nazis at Nuremberg or some other German city some months ago, when one Hans Something-or-Other came up for plea.

“You cannot accuse me of being Nazi” he growled at the court.

“And why not?” asked the court in effect.

“Because,” the kraut replied “I am a deputy sheriff of Los Angeles County, California, U.S.A.”

And darned If he didn’t flash the badge.

Gene was pretty upset about the matter when we called.

“It just couldn’t be” he argued. “I don’t remember him.”

Our memory was better than the Sheriff’s.

We slipped back to the files. And sure enough, there was an interview with the fellow printed in the Los Angeles Times. Before the war, of course.

Steve Harvey’s “Only in L.A.” column in the Times on Sept. 29, 1999, passes this on:

“Retired newsman Roy Ringer wasn’t surprised that Sheriff Lee Baca’s practice of handing out badges to ‘celebrity’ reserves has encountered problems. (One such deputy has been relieved of duty for allegedly drawing a gun outside his Bel-Air home.)

“A half-century ago, Sheriff Eugene Biscailuz handed out honorary badges to celebrities as well as newsmen….”

Harvey says that Ringer recounted Biscailuz phoning to tell him that his badge was found on the person of a robbery suspect. Ringer came to the Sheriff’s headquarters to confront the pilferer of his badge. It turned out that the man had entered Ringer’s car, which was parked at a nightclub; found the badge in the glove compartment; saw Ringer approaching; catapulted himself onto the floor behind the back seat; and exited the vehicle after the reporter parked in his apartment house garage and went off. From Harvey’s column:

“Ringer asked the gunman what he would have done if he had been spotted. ‘With my record,’ the suspect responded, ‘I probably would have shot you.’

“Ringer, by the way, left the badge with Biscailuz.”

![]()

While most saw Biscailuz’s popularity as stemming from his congeniality and big-heartedness, Drew Pearson took a more cynical view. His Nov. 19, 1949 “Washington Merry-Go-Round” column asserts:

The Los Angeles press seems to love Sheriff Biscailuz and seldom points to the fact that it’s in his bailiwick that things are wide open, free and easy. Of course, there may be a reason for this love. Not long ago the sheriff threw a party at the Eastside brewery, with a young army of newsmen present. There was also plenty of bourbon and filet mignon. Just how the sheriff could afford such a party remains a mystery, but his objective was no mystery.

“We’ve all been in this thing together for a long time,” he said, in a little speech of welcome. “So remember your old friend Gene Biscailuz if things start popping. And remember we’ve always been friends.”

|

|

|

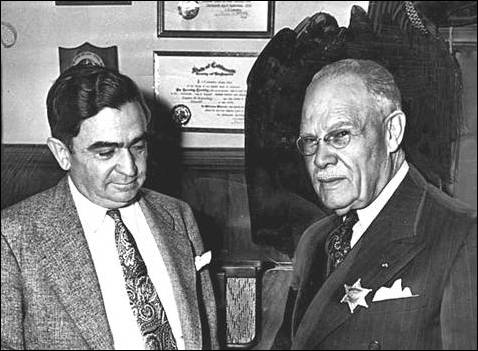

Herald Express Nov. 4, 1940 Biscailuz, at left, with civic leader/historian Boyle Workman, to whom he has just presented a badge. |

A few days later 200 deputy sheriff badges, as big as Pepsi-Cola badges, were handed out to the press.

No wonder, when General [William A.] Worton took over the Los Angeles police and started cleaning up, he was razzed by certain newspapers.

He hadn’t learned the trick of passing out filet mignon, bourbon and deputy Sheriff badges.

While journalistic standards of ethics were considerably looser then than now, I doubt that a public official in Los Angeles, even in 1949, could have purchased a reporter’s fidelity with beef, bourbon and badges, or even higher consideration.

In any event, this points to the fact that Biscailuz did not distribute to reporters press badges, as a form of identification, as the LAPD did until 1940, but gave out to selected journalists the same “Biscailuz badge” presented to former City Council President Boyle Workman, to the courthouse janitor, or movie stars Fatty Arbuckle and Audie Murphy.

![]()

Murphy, a hero of World War II who became an actor and portrayed a deputy sheriff in “Destry” and a sheriff in “Gunpoint,” apparently viewed himself as a real-life lawman, after being entrusted by Biscailuz with a gun and a badge.

A June 6, 1962 Associated Press story tells of Murphy spotting two youths in a car across the street from the home of a friend, Judy Pope. Pope had been receiving lewd letters and phone calls, and Murphy went over to query them as to their possible involvement. The dispatch recites:

“The actor said he flashed an honorary deputy sheriff’s badge and showed the teen-agers a gun in his belt.

“ ‘Then one of them got belligerent and slapped at my flashlight,’ he said. ‘Almost automatically I gave him a little punch in the face.’ ”

The wire service report says the Los Angeles City Attorney’s Office would conduct a hearing to determine whether to file misdemeanor charges…but the youth who received the “little punch” decided not to pursue the matter, a June 13 AP report says.

A May 27, 1970 United Press International dispatch tells of Murphy getting into far more serious trouble:

“Audie Murphy, America’s most decorated soldier whose fortunes plummeted after a brief career as a movie actor, was charged [yesterday] with assault with intent to commit murder in a squabble with a dog trainer.”

Murphy allegedly fired a shot at the dog trainer and missed. He was arrested, tried, and acquitted.

In his 2002 book, “White Horse, Black Hat,” Jack C. Lewis tells of other episodes of Murphy acting like a gun-wielding character from out of the wild west:

“One Hollywood tale of the time involved Murphy’s honeymoon with his new bride, Wanda Hendrix [in 1949]. In bed, they argued over who should get up to turn off the light. Allegedly, Murphy pulled a six-gun from under his pillow and blew the light out of the ceiling!

“His second wife, Pam Archer, a former airline stewardess, recalled that on their honeymoon [in 1951], her new husband had spotted a peeping tom looking in the window of their retreat. Trusty ‘hawgleg’ in hand, Audie went looking for the perp in his pajamas.”

Next: the recall of the Biscailuz badges.

Copyright 2014, Metropolitan News Company