Thursday, October 2, 2014

Page 6

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

City Issues Badges to Non-Police; Abuses Abound; New Badges Render Old Ones Obsolete

…And Then the Cycle Starts All Over

By ROGER M. GRACE

Fifth in a series

From the 1890s to 1940, a way that politicians in the City of Los Angeles could reward supporters, as well as ingratiating themselves to those they wished to have look kindly upon them, was to give out police badges…actual badges, perhaps with numbers setting them apart from those issued to officers, or honorary badges, different from the real ones, but often only slightly or imperceptibly so.

It was a cost-free way for politicos to gain or secure friendships, and the badges that were bestowed could be used in various ways, such as deterring issuance of tickets for speeding, gaining credit, free passage on street cars, or even securing free meals at restaurants.

Recurrently, new and distinctive badges were issued, so that the old ones would obviously not be those of actual officers; vows were made that henceforth, only the police would possess the official badge; badges continued to be distributed to those in favor with city officials; there were abuses; a problem was spotted, and new badges were issued.

The cycle was monotonous and inane, traceable to the fact that L.A. was thoroughly corrupt. Officials liked having the ability to attract favor by handing out the badges, and prominent citizens who received them enjoyed the advantages they secured—resulting in efforts to bring about reform repeatedly fizzling.

![]()

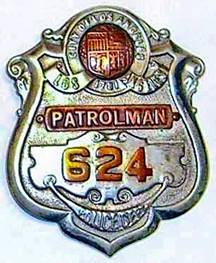

1899

New metallic stars were issued—referred to now as “Series 2”—and an ostensible recall of badges took place.

Street railway operators in the city had been balking about the large number of persons holding honorary police badges who were flashing them to obtain free transportation, to which only actual police officers were, under franchise agreements, entitled. The Police Commission’s Transportation Committee looked into the matter, and its report came before the full body on Jan. 24. An article the next morning in the Los Angeles Herald tells of the recommendations, including these:

“[W]e believe the street railway companies are greatly imposed upon by persons carrying numbered stars for the purpose of receiving benefits, and are credited to the police commissioners of this city. We therefore recommend that all stars now used and issued by former commissions shall be ordered returned to the chief of police within ten days.

|

|

“We further recommend that the chief of police be instructed to provide a new star for the entire police department of this city, to the designed by this commission and numbered accordingly, and that no star be issued without the authority of the majority of this board, and then only to those who are actually in the employ of the police department.”

The commissioners were in agreement on one point: “the chief [was] instructed to call all numbered stars held by others than regular policemen in inside of ten days,” the Herald’s report says, advising that action on other recommendations was deferred.

Just how many badges Chief John M. Glass was able to round up in that 10-day period is not reported.

The commissioners just couldn’t bring themselves to forbidding their own issuance of honorary badges. In the Los Angeles Times’ edition of Feb. 15, it’s mentioned that they decided that what had been wrong with the bestowing of courtesy badges in the past was it had not been required that a majority of the board concur in the actions, and the decisions had been made in secrecy. In the future, they proclaimed, badges would be conferred upon a majority vote, in open session.

New badges did come to be issued and, a Herald report on May 17 says:

“The regular monthly inspection of the police force occurred yesterday forenoon on South Broadway. The men showed up in their summer uniforms, gray helmets and short coats, and made a good appearance. The old emblems of authority have been called in, new stars having been issued yesterday, just before the inspection. The new emblem is a six-pointed silver star, with black enamel letters, the number in the center and the words ‘Los Angeles Police’ above and below. The new star is a great improvement over the unwieldy emblem just discarded.”

The article bears the byline of G. Ray Horton, who was to go on to become an attorney…and was a prosecutor of the McNamara Brothers, charged with the 1910 dynamiting of the Los Angeles Times Building.

The previous badge which Horton terms “unwieldy” had eight points and resembled a sunflower.

Some sources, including the Los Angeles Police Historical Society, say the six-pointed star was issued in 1890. Newspaper reports at the time of the issuance show that it was 1899.

![]()

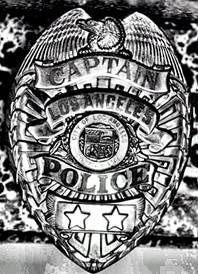

1909

Again, there was an order placed for new badges.

Chief of Police Edward F. Dishman had the “Series 3” badges manufactured—without authorization, and without competitive bidding—apparently believing in the approach that would be advocated nearly a century later by Mayor Richard Riordan: “It’s easier to get forgiveness later than to get permission now.”

|

|

|

—Mike-Snook.com |

The July 2, 1909 issue of the Herald says:

“They were ordered by Chief of Police Dishman because of the necessity for a change in the style of badges worn by the regular policemen. The new badges are in the shape of a shield instead of a star. An investigation has shown there are a number of police stars which are duplicates, and the duplicates are held by persons not attached to the police department. They are used for free transportation on street cars. With the new shields these duplicate stars cannot be used. Policemen appeared on the streets yesterday wearing the new badges, which are considered a vast improvement over the old stars, lifting the Los Angeles force out of the ‘Grassville’ class and placing it in line with the most up-to-date eastern forces.”

The newspaper tells of the City Council calling for an investigation into the matter. It quotes Dishman as commenting on his ordering of new badges:

“It was done to protect the police department. About two months ago an affair occurred that made me decide the old stars were being used by others than patrolmen and for no good purpose.

“Two months ago a man came to my office and demanded the discharge of a patrolman, giving me his number. He stated the patrolman was intoxicated while on an electric car, and had insulted his wife and slapped his face, and threatened him with arrest if he said more. The man said the ‘officer’ showed him his star, and he noted the number. I immediately sent for the patrolman who had the star of that number, and after investigation found the patrolman in question was at the police station making a report at the time of the alleged trouble on the car. It was a case of a duplicate star.

“…I decided to call in all the stars worn by regular members of the police force. I know that there are many persons, some, too, among the higher ups, who have taken advantage of the stars and used them in an unwarranted manner for their personal benefit.

“Since I caused the shields to be issued I have had sixteen applications from persons who desire to wear them and have no right to.

“I wish to state that no person will get a shield unless he belongs to the police department, and that may be one reason for the little fuss.”

Acting to deprive the mayor, members of the City Council, and members of the Police Commission of the ability to give out badges to political supporters and others was not apt to have endeared him to those in power.

Whether that was a factor in his being fired by the Police Commission on Jan. 25, 1910, can only be left to conjecture. No reasons were specified.

![]()

1913

Just four years after the shield replaced the star, the “Series 4” badge came out. This time, it appears, the change was merely for sake of aesthetics; the design unilaterally chosen by Dishman, with its pinched sides, did not meet with general favor.

|

|

|

—Policeguide.com |

A report in the morning Los Angeles Examiner on Dec. 12, 1912 tells of Police Chief Charles E. Sebastian approving a design and sending it to the City Council Finance Committee which had already assured him that funding for new badges would be approved.

The article says:

“The new shield will be of better material and heavier than the present one. It is expected to cost about $2.

“The shield now used costs about 80 cents. This will be third time that the shield of the police department has been changed. Chief Sebastian has been endeavoring for months to secure a new design.”

A Times report that morning advises that “[f]or three years attempts have been made to secure a suitable design.”

A New Year’s Day, 1913, account in the Times says that the City Council appropriated the funds the previous afternoon. That newspaper’s April 18, 1913 edition announces that the annual ceremonial inspection of officers would take place on May 1 and that “the new badges will be worn for the first time” at that event.

![]()

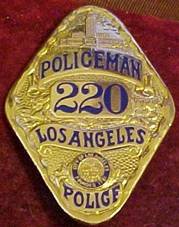

1923

It was at such an inspection that new badges were first viewed by crowds on Feb. 22. A Times story, the day before, says:

“More than 1000 members of the police department, including the band, mounted and motorcycle companies, will parade on Broadway tomorrow afternoon. resplendent in their new uniforms and badges….

|

|

|

—Los Angeles Times Photographic Archive, UCLA |

“Before the parade, the first general inspection since the new uniforms have been issued will be conducted. The new gold badges will be worn for the first time.”

The determination to replace all the city’s police badges—made the previous year—was based on the same reasons underlying the decisions in 1899 and 1909. The Times’ issue of Aug. 3, 1922, tells of Police Chief Louis D. Oaks’ request to the City Council’s Finance Committee for $6,000:

“Chief Oaks has asked for an entirely new set of badges. He says they are needed to equip 300 new patrolmen, but more particularly to replace hundreds of old badges which are now in circulation, some of which are being used by impostors to bilk the public out of money on one pretext or another.”

As the feisty chief pressed for the new badges, he upped his estimate of there being “hundreds” of stray shields to thousands. An Aug. 16, 1922 Times report on Oaks’ appearance before the Police Commission recites his insistence that at least 6,000 of the current badges existed, with less than 1,000 of them in the possession of police officers.

The article tells of Oaks’ desire to come up with “an entirely new type of badge so as to outlaw all of the badges now in use.” It relates that he had vowed to “pass the hat” among the general populace to get funding for badges if the city lawmakers would not provide the funds.

After battling with two members of the City Council’s Finance Committee over whether the new badges would be triangular, which they wanted, or in the form of a shield, upon which he insisted, Oaks won; the City Council appropriated $6,000 for 1,500 new badges, of a design to be decided upon by Oaks and the Police Commission, according to a Times report on Aug. 18, 1922.

Given that the impetus for creating the 1923 “Series 5” badge was a recognition that many of the 1913 badges were in the hands of non-members of the force, it would obviously be necessary to replace the 1923 badges in 10 years or so unless possession of them were restricted, absolutely, to police officers. Newly installed Chief August Vollmer grasped that, and on Aug. 4 issued edicts in the form of “bulletins,” including this command:

“All officers are herewith instructed that no police badges will be issued to any person who is not a duly constituted member of the Los Angeles police department.”

That would, necessarily, entail keeping new badges out of the hands of the mayor, councilmen, and police commissioners—which is what Dishman wanted to do.

An analytical piece on Page One of the Times’ Oct. 16, 1924 issue observes that Vollmer “kept the hands of the politicians off the department” and by virtue of that, “was subjected to such harassment that he was glad to quit when the year was up for which he had agreed to serve.”

![]()

1930

An estimated 5,000 police badges were held by persons who were not LAPD officers, the Feb. 11 issue of the Times reports.

An ordinance was drafted, a May 17 Times article says, to provide for the manufacturing of new police badges which no one would be allowed to possess other than members of the police department, “the Mayor, his secretary, the Police Commission, its secretary, the City Council and the secretary to the Chief of Police,” as well as a limited number of members of the press. It would be a misdemeanor to possess one of the old badges, or be in possession of one of the new ones unless the holder were one of those authorized to have it.

The

list of permissible bearers of badges broadened, ultimately including “[s]uchother city employees as the Board, by resolution,” would decide should havethem.

resolution,” would decide should havethem.

The Aug. 12 issue of the Times tells of the Police Commission instructing Chief Roy Steckel to send a letter to all badge recipients who weren’t connected with the department to turn in their badges to him, admonishing that it would be a misdemeanor to retain them.

As previously noted here, the new badges, which cost 32 cents each, arrived from the manufacturer in Rochester, New York, and were regarded as too shoddy to be worn. The 1923 badges were patched, when necessary, and remained in use until 1940.

Collectors have been mystified by the badge at right because there is no evidence it was ever issued. The item was sold on eBay in July (for $202.50). Here was its description: “An excellent copy of the early 1940s LAPD diamond shape badge that saw little use.”

If it is, as the seller says, a 1970s replica, it is almost certainly a facsimile of the 1930 badge…that saw no use.

![]()

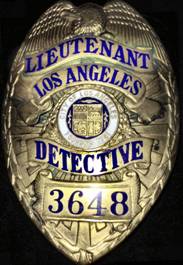

1938

Mayor Frank Shaw was recalled; Fletcher Bowron left the Los Angeles Superior Court to take his place; the atmosphere changed.

Up until that recall, badge collector Keith Bushey notes, “it was very common for elected officials to give out badges to their friends and political supporters.”

Bushey, a retired LAPD commander and former deputy chief of the San Bernardino Sheriff’s Department, recounts:

“In 1938, ‘honorary’ badges became an ugly word and most were called back.”

But thousands of them were out there. Most were a detective lieutenant “honorary badge.” Bushey says that “more than 6,000 were given out.”

|

|

A photo of one of them, supplied by Bushey, appears at left. That particular badge, he notes, “was issued in March of 1937 to a Mr. Elvin M. Johnson of West Los Angeles (probably for a campaign contribution).”

(Records show that there was an Elvin Morgan Johnson who lived on the westside, but he was an unlikely political contributor; a former contractor, he was now a laborer. An Oct. 12, 1944 Times story says Johnson was stabbed just under the heart, and his wife had been arrested. Johnson, then 55, was to live another three years.)

Bushey is co-author with Raymond R. Sherrard and son Jacob A. Bushey, an LAPD sergeant, of the 1996 book, “The Centurions’ Shield.” In it, this information is provided on the honorary lieutenant’s badge:

“During a 1993 interview with the authors, retired Lieutenant Joe Dircks (1923-1943) told us that during his term in office Chief James Davis held a luncheon for favored businessmen and other guests every Wednesday at the Academy. During those events, called ‘shield days’, detective lieutenant badges were given out to ‘friends of the Department.’ While those badges did not read ‘Police’, nevertheless all regularly-appointed detective lieutenants did carry that same badge.”

(The book notes that Dircks told them that if a patrolman wanted a lieutenant’s badge, it could be had for payment of money…with the authors remarking: “That must have caused some complicated identity problems.”)

Although Shaw was recalled, his hand-picked and thoroughly corrupt chief of police remained in office. An Oct. 27, 1938 Associated Press dispatch relates the chief’s rather inventive, and implausible, explanation for the thousands of honorary LAPD badges that had been conferred:

“Issuance of 7843 honorary police badges, Chief of Police James E. Davis declared in a report on file with Mayor Fletcher Bowron today, was in pursuance of the department’s policy of creating an auxiliary force subject to call in time of emergency.”

And who were a couple of the fierce and brawny citizens who would be called into service to do battle with rioters and thugs?

Shirley Temple and Freddie Bartholomew.

The Los Angeles Times’s Oct. 28 edition lists names of the child stars and others who held honorary police badges. Included are evangelist Aimee Semple McPherson, USC President Rufus von KleinSmid, attorney Isidore Dockweiler, movie mogul Louis B. Mayer, Tarzan author Edgar Rice Burroughs, actors Clark Gable, Adolphe Monjou, Leo Carrillo, and Bela Lugosi, radio’s Major Bowes, song writer Al Dubin, and car dealer/radio station owner Earle C. Anthony.

The roundup of honorary badges continued into 1940, the year the Series 6 badge—the one now in effect—debuted.

Copyright 2014, Metropolitan News Company