Wednesday, September 17, 2014

Page 7

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

Reporters Once Toted Firearms; Was a Press Badge a Substitute for a Gun Permit?

By ROGER M. GRACE

Third in a series

A June 18, 1931 article in the Los Angeles Times reports that a coroner’s jury found a fatal gun-blast in a shooting gallery to have been accidental. A revolver discharged, killing a tourist from New York, when the owner of the weapon, a customer at the gallery, was attempting to remove spent shells from the barrels. Why was the fellow there, in possession of a personal firearm? The Times story says his explanation was that “he is a writer and had obtained a police reporter’s badge entitling him to carry a gun.”

Did reporters, back then, actually carry guns—or, in the jargon of the era, “pack rods”? And did a police-issued press badge indeed serve as a substitute for a gun permit?

The answers are yes and…well, maybe.

![]()

The toting of concealed weapons by members of the Fourth Estate had been going on for years prior to the shooting gallery mishap.

In a syndicated column of June 29, 1959, Hugh Baillie, former president of United Press International, provides a first-hand account. Baillie, now deceased, tells of working as a reporter for the Los Angeles Record in 1910-15:

“Covering police, many reporters carried guns. I did. Deputy sheriff badges weren’t worth much, because anybody could buy one at a pawnshop, but the guns gave us a certain security against reprisals from punks and hoods.

“And a police badge was worth cash money; by putting your finger over the word reporter, which ran across the middle of the shield, and flashing the badge at a streetcar conductor, you could ride for free.”

Steve Harvey, in a Dec. 13, 2009 column in the Times writes:

“The late reporter Spud Corliss recalled that when the cops were summoned in the 1920s, ‘the police reporter used to strap on a gun, jump into a hotshot car with the detectives and, with the siren screaming, ride to the scene.’

“Standard equipment for the newshounds included honorary police badges and handcuffs—tools that enabled them to mislead the public into assuming they were cops.”

A July 14, 1987 Times article by Harvey recites that the present Greater Los Angeles Press Club was predated by one which, during Prohibition, “flourished at a time when, as the late Los Angeles Police Chief William Parker once wrote, a reporter’s ‘standard equipment included a police badge and a gun.’ ”

A gun-toting press corps does not appear to have been unique to Los Angeles.

A Nov. 25, 2012 opinion piece in Opelousas, La.’s Daily World, in which the old days of journalism, in the early 20th Century, are recounted, says:

“A number of reporters carried guns in those days and most of them kept a bottle of cheap whiskey in their desks.”

In her 1949 book, “Newspaperwoman,” the colorful Agness Underwood (city editor of the Herald Express), writes:

“Old-time San Francisco newspapermen still speak with awe of Jack Campbell, the San Francisco Chronicle reporter. ‘Jack knows how to use a six-gun,’ one said. ‘He’s shot at ’em and he’s been shot at.’”

![]()

It’s well known that iconic reporter Walter Winchell was armed.

In his May 21, 1942 column, he remarks:

“For many years the Butte (Montana) Daily Bulletin slugged courageously against the no-goods, regardless of how powerful they were. Because of that, they had to keep loaded rifles in the city room—and every reporter had a gun lying beside his typewriter . . . This reporter has also never stopped firing his typewriter guns against the slimy members of our community and country, in spite of all kinds of threats. Yet some people wonder why we tote a .38.”

Bob Thomas, who died in March, authored a 1971 book, “Winchell.” In it, he says of the celebrated columnist/broadcaster:

“He…carried a gun in his coat pocket. One in his overcoat, too. He never used either of them.”

Winchell did have a gun permit. He obtained it the day after a gangster, face-to-face, threatened to kill him, Thomas says.

But were the police reporters in L.A. who had guns under their coats actually exempt from the requirement of a gun permit? Or did they, advisedly, view themselves as possessing a de facto exemption?

![]()

I’ve known persons who would have had the answer. However, I’m posing the question a few years too late; they’re all dead.

The LAPD media relations section spokesperson says all such inquiries on department history are referred to the Los Angeles Police Museum.

I got in touch with author Joseph Wambaugh, son of a police officer from back-when and himself a former LAPD sergeant. He says: “I am uncertain if such a thing was possible in the 20s or 30s,” and recommends contacting the Police Museum.

But an inquiry there is fruitless. Glynn Martin, executive director of the museum, advises:

“I, too, am familiar with the stories about armed reporters of the era. Unfortunately I do not know, and don’t have a means of determining through the museum’s holdings, the answer to your question.”

A reporter or policeman in 1931 of only the age of 20 would be, if alive today, 103. At this stage, I doubt that I’ll find anyone to interview with personal knowledge.

![]()

No law expressly rendered possessors of press badges privileged to carry guns. To the contrary, under a 1930 ordinance, “No person, except a peace officer” was allowed to carry a concealed weapon without a permit.

Yet, they carried badges—the same as those carried by officers except that they bore the word “Reporter” on them.

Could reporters actually have fancied themselves as having the prerogative of carrying firearms based on their lawful possession of an official badge?

Well, Baillie—the one-time head of a major international wire service, and hardly a fool—says in the 1959 column referred to above, with respect to crime coverage here, on the county level:

“Nearly every reporter got some police experience. Every man who covered the sheriff’s office was a sworn deputy, with power to arrest. (During a fight in the press box at an automobile race, two reporters tried to arrest each other. One of them was me.)”

I would doubt that any reporter ever testified in a Los Angeles courtroom in the role of the “arresting officer.”

Yet, other journalists, through the years, have regarded themselves as being possessed of law enforcement powers. A July 6, 1899 column in the Herald by “Gossiper, Jr.” quotes a newspaperman, to whom he lends the name “Smith,” telling of his roommate, a younger reporter, identified as “Jones”:

He is nothing but a kid. The other day he went and had himself made a deputy constable, after the manner of these embryonic newspaper men, and now he wears a badge and imagines himself clothed with tremendous authority. What must he do, then, but arm himself with a pair of those old-fashioned nippers, such as policemen formerly used in place of the improved handcuffs used now. Yesterday morning, before I am fairly awake, I hear a fearful racket in the hallway, and upon going to my door to discover the cause of it. I find Jones dragging the colored chambermaid along the hallway. He has placed the nippers on her wrists and is instructing her in the gentle art of being arrested. She is inclined to demur, but he has his coat off and points to the star and explains to her the authority with which he is clothed. After rescuing the luckless female I take the kid into my room and ask him what he means by such conduct as that. And he tells me that he must get practice somehow, and he can’t think of anybody who will be apt to take it as good naturedly as the chambermaid.

The St. Paul (Minn.) Daily Globe’s issue of July 17, 1893 tells of a movement to establish a system of official press badges being issued in that city. It recites:

“In nearly all of the larger cities the reporters’ badge is issued under the authority of the police department…When the police officials issue the badge they vest the reporter with the privilege of riding on fire apparatus, in patrol wagons, and give them the power of special policemen.”

![]()

|

|

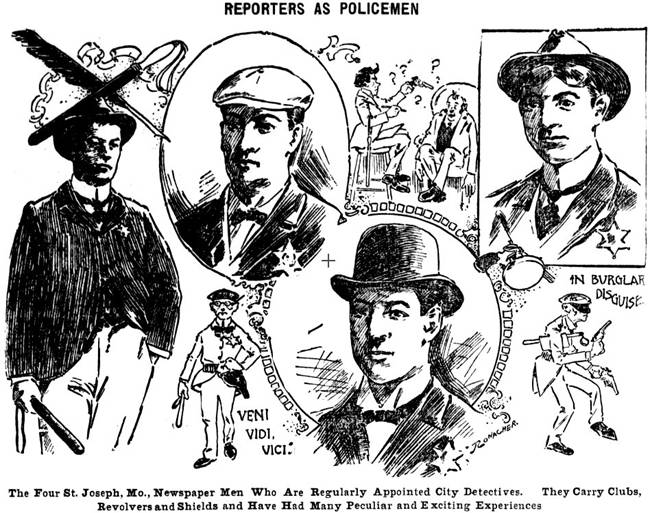

There actually was an experiment in St. Joseph, Mo., in which four of the city’s newspapermen were commissioned as police officers. The illustration at the top appears in the Los Angeles Herald’s Jan. 28, 1899 issue.

Newspapers across the nation in November of 1898 carried an article from the St. Joseph Letter which reports:

“A short time ago the police commissioners gave all the reporters commissions, vesting them with the right to wear stars and carry clubs and with all the powers of the patrolmen. The reporters are not expected to perform any of the work of the patrolmen, of course, and they do not draw salaries from the city, but they are peace officers and can make arrests. While the experiment has not been given a thorough trial, the police commissioners believe it will prove a success. Several of the reporters have already made arrests in the absence tbe regular patrolmen, sending the prisoners to the station in the patrol wagon. They have quelled disturbances on several occasions and the commissioners find that they have added to the force a squad of alert men. scattered day and night in every part of the city and mingling with the throngs, ready for duty at any moment and without a cent of cost to the city.”

As to carrying guns: the four reporters “have been arrested on the charge of carrying concealed weapons,” the article notes, “but they were liberated again when it became known that they were vested with the same authority as the man who made the arrest.”

More on the subject of reporters carrying pistols tomorrow.

![]()

![]()

![]()

FOOTNOTES:

•The man with the press badge who fatally shot a tourist in 1931 was L. Monte West.

It was not clear whether West had actually worked anywhere as a reporter. A June 15, 1931 Times report says of him:

“He produced a police reporter’s badge which local police records show was issued to him on April 22, last, as an employee of the Community News. No record could be found of such a newspaper.”

The June 18 article in the Times, referenced at the outset of this column, reveals that a coroner’s jury found the shooting-gallery death to have been accidental.

West was, however, later convicted of fabricating public records, according to a Sept. 12, 1934, Times article.

The judgment of conviction was affirmed in a brief Court of Appeal opinion on Jan. 15, 1935. The opinion recites that West’s co-defendant, a deputy county assessor, had periodically lent West public funds, with records obfuscating the transactions, and that the borrower’s various $815 checks in repayment bounced. It notes that West had two prior felony convictions.

•In case you’ve never heard of “nippers,” pictured here is one of these “come-along” devices, with a patent date of 1869. It’s being offered for sale on eBay.

|

|

The 1915 edition of Funk & Wagnalls New Standard Dictionary of the English language provides this definition: “An implement like a pair of pincers or tongs: used generally in the plural.”

Copyright 2014, Metropolitan News Company