Tuesday, January 17, 2012

Page 3

PERSONALITY PROFILE: George Deukmejian

East Coast Transplant Who Rose to Governorship Looks Back at Life of Service

By KENNETH OFGANG, Staff Writer

|

I |

T WAS THE 1950S, A TIME WHEN THE GOLDEN STATE WAS JUST THAT, golden, for so many.

The relatively new medium of television laid it out there for all to see. California’s weather was warm, its economy booming, its people brimming with confidence and beckoning for their friends and relatives in the cold weather states to come and join them.

Statistics tell a part of the story. California’s population, 10.6 million in 1950, grew by nearly half during the decade, with personal income growing nearly 150 percent in that time.

Not every California dream worked out, of course. But for a young lawyer from upstate New York, who took his older sister’s advice and came to Los Angeles, the decision worked out beyond anything he says he could have imagined.

He’s been a lawyer, a legislator, attorney general, and governor. Now “trying to be retired,” living “without demands,” George Deukmejian is a 2011 MetNews Person of the Year.

|

|

|

George Deukmejian, who grew up in upstate New York, as an altar boy. |

Now 83, he speaks fondly of the village in which he grew up, Menands, N.Y.—population about 1,700 when he was growing up there, a little under 4,000 today—on the north edge of Albany.

His parents were Armenians who immigrated from eastern Turkey, each in the first decade of the 20th Century, then met in the Albany area. He attended local public schools as his father, also George Deukmejian, worked at a series of occupations.

The elder Deukmejian had worked in New Haven, Conn., as a photographer, before coming to the New York capitol region, where he operated photo shops with a brother. That enterprise was not ultimately successful, and he moved on to a local department store, operating an Oriental rug concession.

That didn’t work out, either. “It was hard to sell Oriental rugs in the Depression,” his son remembers, so he closed down the business and became a jobber, buying paper products which he then sold to retailers.

His mother, he notes, also worked outside the home, at least from the time he was six years old.

Her first job, he recalls, was in a factory in Troy, N.Y. where neckties were made. She later worked at a Montgomery Wards department store and ultimately obtained a job with the State of New York.

There was no high school in Menands, so students there had a choice of schools in nearby communities. He chose Watervliet High School, a few miles northeast of his village and just across the Hudson River from Troy.

The all-consuming event of his youth, as one might imagine, was World War II, which America joined when he was 13.

“The war dominated our life in those days,” he recalls. “Most of the young men went off into the armed services,” while the civilian population adjusted to a new way of life, including rationing of food and other goods and waiting for news from abroad.

It wasn’t easy, “but everyone was sort of united in support of the war effort,” Deukmejian remembers, adding:

“[T]here was not much in the way of any divisions….There was a lot of pride in the way the war was going, especially after D-Day.”

That day—June 6, 1944—happened to fall on his 16th birthday.

It was also a time of great sadness, of course, as over 400,000 Americans—including Deukmejian’s next door neighbor, who perished in the Battle of the Bulge, the winter after the D-Day invasion—lost their lives.

Heads to College

A senior in high school when the war ended, Deukmejian wanted to go to college, an opportunity that had not been available to his immigrant parents or his older sister, who had left high school in order to work. (She later graduated from UCLA.)

Money being scarce, he went to Siena College, a Franciscan institution in Albany. “I was very appreciative that there was an affordable school,” close enough that he could live at home, while working part-time and during vacations, he recounts.

He had several jobs, including serving as the vacation replacement for the only paid member of a local volunteer fire department and filling kerosene tanks for an oil delivery company.

He was also an assistant manager for Tom Thumb, a company that sold ice cream from trucks, with duties that included making certain that the drivers were fully supplied. He also periodically drove ice cream products between Albany and New York City.

His major was sociology, he chuckles. “If it was up to me now I think I would have been a business major,” he says.

He was in a prelaw program, for which he registered on the advice of his mother. He obtained his degree, and was admitted to the law school at St. John’s University in New York City.

“It was reasonable, $300 a semester,” he remembers. His family was able to give him some financial help, and he had heard that St. John’s was a good law school.

Life in the big city was a lot different from that upstate.

“Oh boy, that was a big change,” he remembers. “I’d never been out of my area.”

The law school, which moved to its current Queens location in 1972, was then located in a 14-story building in downtown Brooklyn. Deukmejian and three roommates moved into a Brooklyn apartment building owned by a lawyer who dabbled in real estate.

In an early test of his organizational skills, he and the others put together a household, establishing a rotating schedule of domestic duties. They took turns shopping, cleaning, cooking, and the like, and they all became good friends.

Between studying and work—his landlord helped him pay his expenses by giving him work on another building he had recently bought and was renovating—there was little time for politics, although the school was a breeding ground for future politicians.

A former New York governor, Hugh Carey, graduated from the school a few years before Deukmejian, while Carey’s successor, Mario Cuomo, got his degree a year after the future Californian. Deukmejian didn’t know either man at the time, he notes, although he got to meet both of them later.

Another graduate from that era, Alexander A. Farrelly, became the fourth elected chief executive of the U.S. Virgin Islands. The school once ran ads touting itself as the alma mater of four governors.

Deukmejian had an early interest in politics, although he can’t recall exactly what attracted him to it. “Nobody in my family was active politically,” he notes.

His first campaign, he explains, was that of Thomas E. Dewey, his home-state governor who made his second bid for the presidency in 1948.

“A couple of people in my village were active with the Republican Party, and I got a little job in the campaign,” he recites. “They wanted me to sit in a government office next to a teletype machine connected to Dewey’s train.”

Crisscrossing the country by rail was a favored mode of presidential campaigning then, as it had been since the 19th Century. Taking messages off the machine and delivering them to various campaign functionaries was a perfect job for a college student, Deukmejian explains, because he “studied while I sat there” and because it led to his being named an assistant sergeant-at-arms at the GOP national convention in Philadelphia, which nominated Dewey to oppose President Harry Truman.

Given his precarious financial situation, he says, he “wouldn’t have thought about” accepting the position, “except we had family in Philadelphia, so I stayed with them and went to the convention.”

“I was 20, it was pretty exciting,” he recalls, “to see leaders of delegations, people I’d only read about.”

But any thought of a political career of his own was a long way off, he explains. Not only did he have college and law school to finish, but he had a military obligation.

There was a Korean War-era draft, and his induction had been deferred as long as he was a student. So in June 1952, he graduated from St. John’s, passed the New York bar exam, and took a state job he knew would be temporary while he waited for the call from Uncle Sam, which came in February 1953.

“I was sent to Ft. Dix [in New Jersey] for 16 weeks of infantry basic training,” he explains, “and got into the best shape I’ve ever been in.”

Coveted Assignment

As a law school graduate, and despite the fact he was no more than “a buck private out of basic training,” he was able to wangle a coveted assignment to Paris as a member of a team that evaluated financial claims by French civilians. It was interesting work, as the claims varied from being assaulted by GIs in bar or street fights, to being in auto accidents with military vehicles, to serious accusations like sexual assault.

It was more like being a lawyer than a soldier, he notes, as a handful of military personnel worked in an office with 22 French civilians, mostly translators. “The French being the French, this is 1953, they want to rebuild tourism and the economy, and didn’t want a lot of soldiers in uniform.”

|

|

|

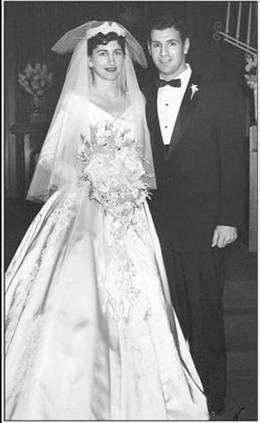

Gloria and George Deukmejian on their wedding day. |

So PFC Deukmejian was given a subsistence allowance to live in the city and buy civilian clothing. He later was sent to Fontainebleu, about 30 miles south-southeast of the city center, where the Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe, or SHAPE, was established, to “brush up on tactics,” although the Army “never asked me to go out on a firing range or anything like that.”

He returned stateside in 1955, going home to Albany, at first. But his sister had moved to Los Angeles with the man she married in 1950, and she encouraged her younger brother to visit, so he made a cross-country drive.

He liked what he saw, and so he flew home, wound up his affairs, and moved to California for good.

He couldn’t practice here, of course, so he got a job with Texaco in its Land and Lease Department while studying for the bar exam. Failing on the first try was “discouraging,” he says, but in retrospect is understandable.

“I was rusty, and I didn’t know California law,” he explains. He passed on the second try and was hired as a deputy county counsel, one of only about three dozen lawyers in the office at the time.

The county counsel was Harold Kennedy, who held the job from 1945 to 1967. Deukmejian, who was assigned to work on air pollution issues, says he met “a lot of wonderful people,” including Baldo Kristovich, who later became the county public administrator/guardian, and John Larson, who later became county counsel.

But while he enjoyed the work and the people, Deukmejian says, he only stayed a year and a half. “I didn’t want to be in the public sector forever,” he explains, and he was taking on new responsibilities.

Living on the Westside at the time, he had met Gloria Saatjian, a Long Beach resident, at a wedding in Pasadena, and they were married in 1957. He moved to his wife’s hometown and began looking for opportunities in private practice.

He noticed that the Belmont Shore area of the city was virtually unlawyered. “[The attorneys] were all downtown,” Deukmejian explains, so “I hung up my shingle” on the second floor of a bank building, specializing in “anything that walks in the door.”

He joined the local business association, where he gained a number of small businesses and individuals as clients, and was soon asked to serve as the group’s president. That led to a stint on the board of the Long Beach Chamber of Commerce, and a chance to meet the city’s “movers and shakers,” he recalls.

He also volunteered to help Republican candidates, including the local assemblyman, William Grant, whose 1960 re-election effort he volunteered for.

“I didn’t think he needed help,” Deukmejian recalls, because Grant was popular and the area was heavily Republican. “But he said ‘I’d like you to be my campaign chairman.’ He didn’t need one, but he said he wasn’t going to run again,” and the post gave the young lawyer a chance to test the waters for a future effort of his own.

The Deukmejians had no children at the time, and the Legislature was an attractive place for an upwardly mobile young lawyer because the work was part-time.

The Legislature back then met in regular session for six months every other year, and in the alternate year would meet for just 30 days in the budget session. So after talking it over with his wife, Deukmejian took the plunge and entered the 1962 GOP primary for Grant’s seat.

He defeated three opponents, most notably James Hayes, who was elected to the Assembly four years later when Deukmejian moved up to the Senate, and later became a county supervisor. He then beat the vice-mayor of Long Beach, Bert Bond, in the general election.

Budget Sessions

His plan to represent the people and earn a living at the same time hit a snag, however. While the budget session could only act on budget-related items, the governor had the power to call lawmakers into extraordinary session concurrent with the budget session.

On top of that, the three budget sessions during which he served—the budget session was abolished by constitutional amendment after the 1966 session—all failed to pass a budget, so lawmakers had to stay in Sacramento and pass one in extraordinary session.

Those sessions “just kept getting longer and longer” as the legislators faced Gov. Pat Brown’s ambitious agenda, Deukmejian recalls.

And then came 1966, one of the busiest years of his career. In addition to the lengthy legislative calendar, he had a new electorate to face.

The U.S. Supreme Court had handed down a series of decisions between 1962 and 1964 known as the “one-man, one-vote” cases. The court said that legislative and congressional districts could no longer be drawn so as to make the votes of rural residents worth more than those of voters in urban areas.

While the California Assembly at the time was apportioned on the basis of population, the state Constitution provided that no county could have more than one senator. So Los Angeles County, with nearly 40 percent of the state’s population at the time, was represented by just one of 40 members of the upper house.

Under judicial mandate, the California Senate was reapportioned, giving Los Angeles County its proportional share of the upper chamber, some 13 seats.

One new district, the 37th, ran through the cities of Long Beach, Whittier, Hawaiian Gardens, Norwalk, Dairy Valley—later renamed Cerritos—and La Mirada, and Deukmejian won it with 69 percent of the vote.

That was the same year Ronald Reagan won the governorship, upending Brown’s bid for a third term. Political consultants Stu Spencer and Bill Roberts—who later worked for Deukmejian—were running Reagan’s effort and brought the up-and-coming legislator from Long Beach into the campaign.

They met at the Lafayette Hotel in Los Angeles. Deukmejian says he and Reagan hit it off immediately, and “remained friends until his passing.”

After the election, the new governor asked the new senator to head up a group of lawmakers dedicated to implementing Reagan’s legislative program.

And the first bill that the conservative governor asked the conservative legislator to carry, Deukmejian notes, shaking his head, was a tax increase.

Full-Time Legislature

But while taking on more responsibility in the Legislature, Deukmejian had personal business to attend to. As if his solo law practice hadn’t suffered enough with the extended sessions, the 1966 election saw the enactment of a ballot measure backed by the Assembly’s top Democrat, Jesse Unruh, to eliminate the budget session and allow annual sessions of unlimited length.

It was, in effect, the beginning of the full-time Legislature, although lawmakers were still allowed to have outside business interests.

“I realized I needed partners,” Deukmejian recalls, and formed a partnership that included brothers Malcolm and Campbell Lucas. Malcolm Lucas—whom Deukmejian later appointed as the state’s chief justice—left the firm in 1967, because Reagan appointed him to the Los Angeles Superior Court.

|

|

|

Then state Sen. Deukmejian and then-Gov. Ronald Reagan. |

The Lucas brothers were well-established in Long Beach, having practiced together since 1954. Malcolm Lucas had met Deukmejian at a bar meeting, he recalls.

“The quality I recognized right away was that this guy radiated honesty and integrity,” Lucas says. As a lawyer, he refused to take on matters that smacked of a potential conflict with his legislative duties, even when the looser ethics rules of the time would have allowed it, Lucas says.

“From the beginning and all throughout his career, George took his role as an advocate and representative of the people very seriously,” the former chief justice, now a private judge, comments. “George was always well-liked by both sides. He worked well with...opposing counsel and [in public office with] those of differing political views.”

Campbell Lucas—who later was appointed by Deukmejian as presiding justice of Div. Five of this district’s Court of Appeal and is now deceased—received his own Superior Court appointment from Reagan in 1970. That led Deukmejian and another lawyer who had joined the firm, Donald Dyer, to merge their practice with a well-established Long Beach firm, Riedman, Dalessi & Woods, which became Riedman, Dalessi, Deukmejian, Woods & Dyer.

Then-partner Fred Woods is now a justice of Div. Seven of this district’s Court of Appeal, to which Deukmejian appointed him in 1988. Deukmejian, he says, was a “fine lawyer,” who “built his practice based on a good reputation.” Although legislative duties continued to occupy much of his time, “we were lucky to have him,” the justice says.

The men knew each other well before they practiced together, the justice explains, because they were active in the same Long Beach church. Much of Deukmejian’s success, he says, can be attributed to the fact that “he is exceptionally forthright and honest.”

Woods also tells an anecdote about the ex-governor’s modesty and workmanlike attitude.

The two men spoke not long after Deukmejian left the governorship and joined the law firm of Sidley & Austin in its downtown Los Angeles office, and Woods suggested that he commute from Long Beach to Los Angeles on the Metrorail Blue Line and catch up on work, as the justice usually does.

“He gave it a try,” Woods explains. Deukmejian sat down unobtrusively, took out some work, and started reading, and was doing just fine until someone recognized him and said, “Hello, governor.”

So much for getting work done on the Blue Line, Deukmejian told him. He quotes his ex-partner as saying: “I signed autographs all the way to L.A.”

Gaining public attention with his advocacy of anti-crime legislation, Deukmejian rose to the Republican Senate leadership within three years, and decided to run for attorney general in 1970. While some law enforcement groups backed him, he came in last of four candidates, as the better known and better funded Evelle Younger, district attorney of Los Angeles County, won the primary and later, the general election.

Fortunately for Deukmejian, some quirky legislative politics enabled him to run statewide without giving up his Senate seat.

Normally, in California, senators serve four-year terms, with half of the Senate elected every other year. But because of the mandated reapportionment, the entire Senate was up for election in 1966, but half the senators only got two-year terms.

That half was made up of senators from odd-numbered districts.

New District

The new Long Beach district was originally supposed to be the 34th, meaning that Deukmejian would have had a four-year term and been forced to choose between the Senate and the attorney general contest in 1970. But John Schmitz, the ultra-conservative Republican who had been the sole senator from Orange County, and was thought to be controversial enough to be at risk of losing a primary, balked at being reapportioned into a two-year term, so the numbers were switched.

Deukmejian thus started with a two-year term, then won a four-year term with 91 percent of the vote in 1968, when only the American Independent Party put up an opponent.

William Bagley, a Northern California Republican who served with Deukmejian in the Legislature, says negotiating the switch in districts was a perfect example of “George’s perspicacity.” It left Schmitz “happier than a Bircher at high tide,” while freeing Deukmejian to run for attorney general in 1970, and thereafter, without giving up his Senate seat.

“There’s nothing better in politics than a free ride,” the ex-senator says.

Bagley adds that it worked out for him, too, as Deukmejian appointed him to the Public Utilities Commission and later as a regent of the University of California.

Today, he applauds the former governor for many things, including his financial support for the UC, which Bagley says was “starved” under both Reagan and Jerry Brown. The self-described “evangelical moderate,” now registered decline-to-state after years of criticizing what he considers to be extremes in both major parties, describes Deukmejian as a “thoughtful conservative, not an ideologue” and as “the only governor I’ve known—and I’ve known them all—without a built-in ego.”

In 1974, with Younger expected to run for governor, Deukmejian was preparing for a second try at the attorney general’s post. Fundraisers were held around the state, but Younger—who wound up running four years later and losing to incumbent Jerry Brown—decided the timing wasn’t right and ran for re-election instead.

So Deukmejian curtailed his campaign, and refunded donations to contributors.

Friends and advisors, Woods notes, “told him just to hang on to the money” for a future race. But Deukmejian insisted on giving it back, saying, “It’s not my money,” the justice recalls.

“That’s the type of person he is,” Woods explains.

While he wound up not running in 1974, he retained the allegiance of supporters, who were there for him again when he won the office in 1978. One of those was Marvin Baxter, a Fresno lawyer at the time and now a state Supreme Court justice.

Baxter, who had left the Fresno District Attorney’s Office for private practice prior to the 1970 campaign, said he became involved through a friend of Deukmejian’s who was a deputy probation officer. While he had never met Deukmejian, he explains, he had begun to admire him while working in Sacramento as a Coro fellow during the future governor’s first Assembly term.

“He was an outstanding rookie legislator,” Baxter remembers, as well as a role model for young Armenian Americans like himself. “It was highly unusual to see anyone of Armenian ancestry in public service,” he notes.

The 1970 race was an uphill battle, though.

“He was a very young legislator,” Baxter recalls. “And he didn’t have the funds or exposure to compete effectively against Younger.”

Single Opponent

With Younger running for governor in 1978, the stage was set for another Deukmejian run for attorney general. Better known and better funded than before, he had a single primary opponent, James L. Browning Jr., a former U.S. attorney for the Northern District of California.

Browning had gained some publicity as the lead prosecutor in the Patty Hearst case, and had been a respected deputy district attorney in San Mateo County, but could not compete with Deukmejian, who had burnished his law-and-order credentials considerably by heading a successful initiative to restore the death penalty in 1972. (The issue was so popular, the winning campaign cost all of $10,000, the ex-governor notes.)

|

|

|

Deukmejian and Gerald Ford, prior to Ford becoming president. |

Easily dispatching Browning—whom he later appointed to the trial bench in San Mateo County—in the primary, Deukmejian was an early underdog in the general election, in which his opponent was Yvonne B. Burke, then a member of Congress who had won a close Democratic contest with Burt Pines, then the Los Angeles city attorney.

The race tightened as the campaign went on, with the final Field Poll showing Deukmejian up two points, well within the margin of error. The final result wasn’t close though, as Deukmejian won by better than nine percentage points.

Looking back, Burke—who later became a Los Angeles County supervisor—says the state may not have been ready for an African-American woman in the post, 32 years before the election of current Attorney General Kamala Harris. But she adds that Deukmejian did well as attorney general, and said she “never had any problems working with him” when he was governor.

Burke, Deukmejian says now, was simply ill-suited as a candidate for that particular office. The electorate viewed the attorney general as the state’s chief crime-fighter, a role that he sought with relish.

Although Brown was re-elected governor in 1978, there was a conservative mood in the state, as voters that year approved another death penalty initiative—the one Deukmejian had sponsored six years earlier was thrown out by the state Supreme Court, as had a law he sponsored to restore it, which the Legislature passed over Gov. Jerry Brown’s veto—as well as tax-cutting Proposition 13. Burke, a liberal Democrat who had voted during her earlier service in the Legislature to replace the death penalty with life imprisonment without possibility of parole and had expressed the view that the punishment was administered unfairly, seemed out of touch with the times.

Advocacy of capital punishment was not only good politics, Deukmejian says, it was good public policy.

“I thought you had to have that ultimate punishment for that ultimate crime,” he explains. “If you believe as I do that life is sacred, you have to do everything you can to protect that life. Government has to protect the life of innocent citizens.”

As attorney general, he argued personally in two cases—one on the death penalty and the famous Tanner case in which the state high court upheld the “Use a Gun, Go to Prison” law.

Attorney general is “a fine job,” he says, adding he “would not have been particularly unhappy serving another term or two.” But with Brown leaving to run for the U.S. Senate, “some of my friends said this is the time to [run for the governorship.].”

The argument that won the day, he says, became encapsulated in a quote that became a staple of the campaign:

“Attorneys General don’t appoint judges—Governors do.”

Many of Brown’s appointments to the bench, in particular Chief Justice Rose Bird, had come under heavy criticism. “Jerry’s judges,” as they were dubbed, were often liberal, more concerned with making policy than following the law, and often inexperienced, critics charged.

If elected, Deukmejian vowed, he would appoint a different kind of jurist, a pledge he made good on later.

No Cakewalk

But the road to the GOP gubernatorial nomination was not the cakewalk that the attorney general primary had been. Lt. Gov. Mike Curb got a jump on the attorney general and had raised $1 million, “which in those days was a lot of money,” Deukmejian says.

“We started late and had a lot of catching up to do,” he recalls, but was able to raise more than $8.5 million with the help of a finance committee headed by Los Angeles attorney Karl Samuelian, a partner in the firm of Parker, Milliken, Clark, O’Hara & Samuelian.

Samuelian, now retired from the firm that still bears his name, said he knew Deukmejian during his time as a state senator and attorney general, and was attracted to a fellow Armenian American.

“I believed in him,” the attorney explains. “He was a solid candidate,” someone to whom donors were attracted, “very strong on fiscal issues and on law enforcement issues.”

“He knew what he was talking about,” Samuelian says, “and he was 100 percent credible.”

Deukmejian, he adds, fulfilled the expectations of his donors and supporters, particularly those who, like Samuelian, were concerned with the caliber of judicial appointments.

“He appointed a lot of good judges,” the finance chairman says. The time and effort he put into that role, Samuelian—who also served during the 1986 re-election campaign, which raised over $13 million—declares, was “absolutely worth it.”

Polling in the primary campaign showed several lead changes, with Deukmejian moving ahead following the disclosure that Curb hadn’t voted until he was 29 years of age, sitting out both of Reagan’s campaigns for governor.

The attorney general ultimately beat the lieutenant governor by about seven percentage points, and went into the general election an underdog to Los Angeles Mayor Tom Bradley, whose path to the Democratic nomination had been considerably smoother.

“We were behind the whole way,” Deukmejian recalls, and news outlets were projecting a Bradley victory on election night.

“I thought it was all over,” around 10 or 11 p.m., he recalls, as various pundits were explaining how Bradley had won the election. But some of his inner circle, he says, convinced him that all was not lost, that he could still pull the race out because much of Orange County, the GOP’s No. 1 stronghold in the state, was still to be counted.

“I finally determined that maybe we had a chance,” Deukmejian recounts. “When all the votes were counted, we won by 93,000.”

‘Dificult’ Transition

The transition from a liberal Democratic administration to a conservative Republican one, was “very difficult, very demanding,” he says. “You have to start making key appointments— the governor’s immediate staff, major agency heads— deliver an inaugural address, deal with the budget [and] make an address to the joint session of the Legislature. And all of this over the holidays.”

Before he took office, though, there was one last clash with Brown, over judicial appointments.

The Legislature had authorized the creation of a Sixth District Court of Appeal, based in San Jose, and the governor had nominated Edward Panelli, then a Santa Clara Superior Court judge; Sidney Feinberg, who would have moved over from the First District; and Jerome Cohen, a former general counsel for the United Farm Workers.

Judicial Appointments

On Dec. 29, 1982, the three nominees faced the Commission on Judicial Appointments, which normally consists of three members. But because the Sixth District didn’t yet exist, it didn’t have a presiding justice, so the commission consisted of only two members—Bird and Deukmejian—both of whom would have to vote in favor for a nominee to be confirmed.

Never before had the commission, which was created in 1934, rejected a nominee, nor has it since. Deukmejian, however, abstained as to Panelli and voted against the other two, killing all three nominations.

Contemporary news accounts of the hearing show it was contentious, with the attorney general engaging in heated argument with Feinberg, whom he described as being “adverse to the people” in criminal cases, and with Cohen, whom he described—based on reports by unnamed sources—as “rude, foul-mouthed, dishonest, devious and unethical.”

Cohen responded by accusing the attorney general of McCarthyism, then telling him:

“Don’t feel bad, though. I didn’t vote for you, either. “

Deukmejian later explained that he could not vote for Panelli at the time because there was little point to confirming one justice to a court that could not sit without three. Instead, he appointed Panelli to a First District vacancy the following year, made him the first Sixth District presiding justice the year after that, and elevated him to the Supreme Court in 1985.

Critics accused Deukmejian of playing politics, saving the appointments for himself, and specifically of rejecting Cohen because he was despised by growers, many of whom were big contributors to the governor-elect’s campaign. (Cohen, who could not be reached at the phone number listed for him on the State Bar website, recently donated a collection of private papers to his alma mater, Amherst College. He included a file of documents on the confirmation battle, including a list of Deukmejian campaign donors.)

Deukmejian says he was just doing his job.

|

|

|

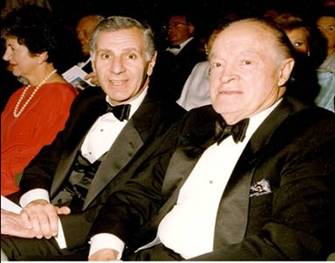

Deukmejian and Bob Hope. |

“I started asking questions and they didn’t like it,” he explains. “Some people think the governor is elected, and it’s his responsibility to make appointments and they should simply be confirmed. Others think the commission should make an independent judgment.”

His own views, he said, were right in the middle. He notes that he had voted to confirm numerous Brown nominees, many of whom he had philosophical disagreements with, but he says there were limits.

“I really felt that I was giving great deference to the governor, but there were certain questions that had to be asked,” he explains. “People needed to know where the nominees stood and some of the nominees wouldn’t answer, or would answer only begrudgingly.”

He was sworn in as governor five days after the hearing.

Transition Team

He brought in a transition team, headed by Steven Merksamer, a senior aide in the Attorney General’s Office. After taking office, he named Merksamer as chief of staff and Baxter, who left his practice in Fresno, as appointments secretary, which included responsibility for judicial appointments.

Deukmejian was a great boss as well as a great governor, the now-Supreme Court justice says:

“He was a very thoughtful and pragmatic individual, and he was unflappable. He has a demeanor such that nothing throws him off course. He stays focused and always checked and double checked to see if the information [about a potential appointee] was correct. The person was thoroughly vetted.”

As expected, the new administration appointed many judges from the ranks of prosecutors, as well as business lawyers. But both Deukmejian and Baxter say they are especially proud of their efforts to diversify the bench, particularly when it came to women lawyers.

Working with Judith Chirlin, serving as liaison between the administration and California Women Lawyers and later a Deukmejian appointee to the Los Angeles Superior Court, Baxter came up with an impressive list of judicial appointments, male and female, the ex-governor says.

Chirlin, now executive director of the Pasadena-based Western Justice Center Foundation, says the governor “did a terrific job,” with women gaining 20 percent or more of the judicial appointments. That may not seem like an overwhelming number today, she explains, but it is when you consider that the pool of eligible women—you had to have been a lawyer for five years to be a municipal court judge, 10 years to serve on the superior court—was much smaller than it is now.

The early days of Deukmejian’s governorship were difficult, he says, because the Democrats still controlled the Legislature, and many battles lie ahead.

“I hate reliving those things,” he says. “I had been elected by the voters, I told them what my promises were, and the Legislature is doing everything they can to stop me.”

Early on, the Senate rejected his appointment of Michael Franchetti, his former chief deputy attorney general, who had worked under Merksamer on the transition team, as finance director.

He realized, he says, that the lawmakers had their own ideology and constituencies to answer to, and that his small victory margin didn’t help. “I hadn’t been elected by a landslide, but I was a former legislator. I thought they’d give me a little deference.”

At first he tried to reason with them, he says.

“I went up to meet with the entire Senate Democratic Caucus,” he notes, continuing:

“These had all been colleagues of mine, but they never gave me anything but grief.”

He soon realized, he says, that he had to use the prerogatives of office “to do what I could without going to the Legislature,” such as appointing “the right people” as agency heads and as judges. And while he often couldn’t get his own bills through the Legislature, he could certainly veto the ones it sent him.

His 436 vetoed bills are the most ever by one governor, according to state records. And he used the line-item budget veto about 4,000 times, cutting $7 billion in spending.

The ‘Big 5’

After disastrous experiences like his meeting with the Democratic senators, and additional meetings with Democratic committee chairs, some of whom “were nothing but confrontational,” he developed a new approach.

“I finally told the staff we’re not accomplishing anything,” and that from then on, Deukmejian says, when he needed to meet with legislators, there would be five people in the room—himself, the president pro tem of the Senate, the speaker of the Assembly, and the minority leaders of the two chambers. “That’s how the ‘Big 5’ got started,” he explains, referring to what became a standard mode of operation.

The approach worked, he notes, because the speaker at the time, Willy Brown, D-San Francisco, “was a very pragmatic leader.” Brown, he says, “knew his caucus very well” and “could tell me whether he had the votes for something or didn’t.”

Brown, he jokes, “would [publicly] call me the part of the horse that went over the fence last, but we worked well together.” Relations with Senate President Pro Tem David Roberti, D-Los Angeles, were a little more complicated, he posits, because power in the Senate is less centralized.

|

|

|

Deukmejian and then-U.S. Sen. Bob Dole, R-Kansas. |

“He had a balancing act with the Rules Committee,” Deukmejian explains, “but it all worked out pretty well.” The administration “accomplished what we set out to do,” including creating an improved business climate, he comments.

Deukmejian entered the 1986 campaign as an odds-on favorite for re-election. The state’s economy was doing well, voters were giving credit to the governor for bringing the state budget into surplus after discovering a $1.5 billion deficit when he took office, and his criticism of the liberal majority on the state high court was resonating.

He made the still-controversial decision to announce that he would vote against three incumbents on that year’s retention ballot—Bird and Justices Cruz Reynoso and Joseph Grodin. All three were swept from office, the only three members of the appellate bench to suffer that fate in the 78 years since contested elections for those positions were abolished.

Deukmejian rejects criticism from those who say that his opposition to the three was an attack on judicial independence.

He points out that he opposed an earlier effort, led by Sen. H.L. Richardson, a very conservative Republican from the eastern San Gabriel Valley, to recall Bird from office. Disagreement with a justice’s decisions is “not what the recall is for,” he says.

But the retention election, Deukmejian argues, is an appropriate forum for examination of all aspects of a judge’s career. “It’s not a contested election, but it is an election,” the former governor remarks.

The result, he says, was not surprising. “They were very, very unpopular.”

His own role in their rejection, he adds, should not be overstated.

“My involvement was mainly just stating that I was not going to vote for them,” he says, while the actual campaign was conducted by a coalition of Republican and victims’ rights groups. He was busy with his own campaign, he notes, in which he defeated Bradley again, but this time by a landslide.

The actual work of taking on Bird, Reynoso, and Grodin at the ballot box was done by others, including Robert Philibosian, who had served as Chief Deputy to then-Attorney General Deukmejian and later as Los Angeles district attorney.

The success of the campaign, Philibosian says now, enabled Deukmejian to appoint conservative justices to the court and “literally changed the course of California history.”

‘A Real Legacy’

While Deukmejian did many great things as governor, Philibosian says, his judicial appointments were “a real legacy.” He “appointed people who would adhere to the ethics and principles” that he himself espoused, and many of them still serve today, the former district attorney, now a lawyer in private practice in Los Angeles, comments.

Reynoso, unsurprisingly, takes a different view.

The goal of those who created the retention-election system, he says, was to replace a process in which judges “spent so much time on politics that it wasn’t serving the people well” with one that would enable the public “to get rid of judges who were not doing their job.”

His ouster, he says, was contrary to that goal, he says, because “no one suggested that Rose Bird, myself, and Joe Grodin weren’t doing our job.” Deukmejian, he says, was “a principal part of misleading the people about the role of the court,” scaring them into thinking that death penalty reversals were going to result in murderers being put out on the street.

“That was totally false,” he says, “a sad part of the history of California.” The governor’s role in the campaign, he says, “served the people of this state very poorly.”

As the easily re-elected governor of the nation’s largest state, Deukmejian became the subject of the inevitable talk about being on the national ticket in 1988. California was considered a battleground state then, and some thought that as the vice-presidential nominee, he might make the difference in the outcome.

|

|

|

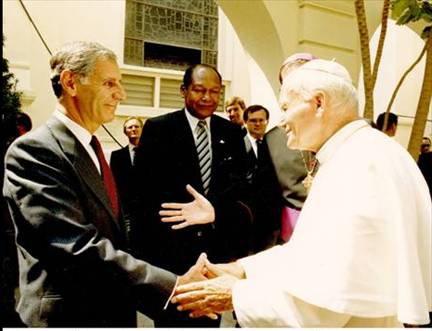

Deukmejian with Pope John Paul II, who visited Los Angeles in 1987. In the background is then-Los Angeles Mayor Tom Bradley, whom Deukmejian had defeated the year before. |

But had he been elected vice president, then-Lt. Gov. Leo McCarthy, a Democrat, would have succeeded him. So he wrote then-Vice President and presidential nominee George H.W. Bush in August, while on a trade mission to South Korea, saying he could not be considered.

He had no animus against McCarthy, he explains, but if he had left office at the time, the Democrats would have had full control of the executive and legislative branches of government. He says he “couldn’t bring myself to do that, to benefit me personally.”

If the situation had been different, he says, and the nomination been offered, he “probably would have done it” although “it wasn’t anything that I had a burning desire to do.” Every office he ran for was at the state level, he notes.

“I could have run for Congress when [a Long Beach-area seat opened up while] I was in the Senate,” he says. “I never had that drive to go to Washington.”

No Third Term

As the 1990 election approached, Deukmejian neither encouraged nor discouraged speculation that he would run for a third term. While some journalists reported that he was “sending mixed signals,” he now says he never considered running, but waited until close to the filing period to announce he would not do so because he was not about to let the Legislature treat him like a “lame duck.”

“It had been 28 years” in public office, he points out. “That was enough. I accomplished what we set out to do. I never dreamed I’d be governor of California….I was very thankful, but it was time to turn it over to some younger people.”

He decided to return home to Long Beach, and to practice law in the Los Angeles area. He says he spoke to eight law firms before settling on Chicago-based Sidley & Austin, “a very large and old firm going back to the days of Abraham Lincoln.”

He was impressed with the firm’s “good Midwestern culture,” he says, and they were “very good to me.” He didn’t do any lobbying, he explains, but did advise clients with governmental issues “across a lot of different practice groups.”

He chose to end his career there, rather than serve as attorney general of the United States, he relates.

New Surroundings

It was 1991, his first year at Sidley, “I was just sort of getting used to my surroundings and for the first time in my life I was starting to make some money,” he explains. He was in Washington on business, and was renewing acquaintances with President George H.W. Bush, who had narrowly carried California with the governor’s help, as well as with two former governors, Attorney General Richard Thornburgh and Bush’s chief of staff, John Sununu.

Thornburgh was planning to leave office to run in a special election for the Senate in Pennsylvania. At one point during the meeting, the attorney general and Sununu stepped out, so Deukmejian and the president were alone, and the president told him, as he recounts it:

“I know you and John have talked about [succeeding Thornburgh] and I really want you to consider it.”

He declined, he explains, but “I told him ‘If you can’t get anybody else, I’ll reconsider it.’ ” The president subsequently appointed Thornburgh’s deputy, William Barr, to the position.

Quiet Retirement

Deukmejian remained at Sidley until 2000, then moved on to a quiet retirement in Long Beach, where he is still one of the city’s most recognizable citizens. He recently attended the groundbreaking for the new courthouse in the city, which will be named for him.

State Sen. Alan Lowenthal, D-Long Beach, strongly supported the renaming. The ex-governor and his wife, he says, “have achieved almost beloved status” in the city.

Deukmejian, the senator says, “has served his city and state so well…I can’t think of anyone who deserves it [to have the courthouse named for him] more.”

Copyright 2012, Metropolitan News Company