Wednesday, March 2, 2011

Page 7

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

Sutherland’s Service as DA in Los Angeles Established by Records, Overlooked by Historians

By ROGER M. GRACE

140th in a Series

THOMAS W. SUTHERLAND’s name does not appear, so far as I can tell, in any of the various tabular lists of district attorneys who have served during Los Angeles County’s history—but his name does gain fleeting mention in various sources in connection with Sutherland having supposedly been “acting district attorney” during a celebrated case in the early 1850s. He wasn’t; he was the DA.

Sutherland, as I’ve noted, was the second man to serve as chief prosecutor here…and is one of two “lost” DAs, along with Lewis Granger. (Also, historians have overlooked one of Albert B. Chapman’s two stints in office in the 1860s.)

To recap from a previous column: William C. Ferrell on April 1, 1850, was elected district attorney of California’s First District, comprised of Los Angeles and San Diego counties. On Oct. 7, 1850, he was reelected, without awareness by folks on this remote side of the continent that California had been granted statehood on Sept. 9 and that Ferrell had been confirmed by the U.S. Senate on Sept. 30 as collector at the Port of San Diego. Minutes of Jan. 10, 1851, for the dual-county District Court, convened in San Diego, note that Ferrell “had resigned the office of District Attorney” and recite that the district judge, Oliver S. Witherby, appointed Sutherland “to fill the vacancy occasioned by said resignation.”

![]()

The District Court some months held sessions here, some months in San Diego—and some months, conducted no proceedings.

At the Seaver Center for Western History Research in Exposition Park, located in the Museum of Science and Industry, I examined the original of the “Minutes of Proceedings in the District Court 1850-51.” These are the minutes that were kept in Los Angeles for proceedings held here (with a separate set maintained in San Diego, now preserved by the San Diego Historical Society).

Entries for the February term, 1851, which took place here, reflect Sutherland’s status as district attorney. On Feb. 6, in the case of People v. Nansant, it’s recited: “Now comes the Plaintiffs by Thomas Sutherland Esq. District Attorney….” Minutes relating to one proceeding on Feb. 12 say: “And now at this day comes the parties in this cause by Sutherland Dist. Atty....” Also on that day, in another case: “Sutherland for State as district attorney.” On Feb. 15: “Sutherland Esq as District Attorney.”

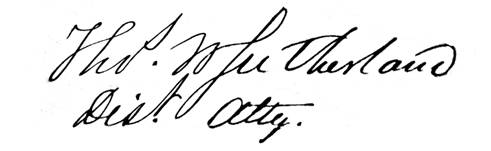

In a folder with loose papers, I came across a criminal filing alleging assault with intent to commit murder in People v. Norris. It bears this signature of “Thos. W. Sutherland, Dist. Atty.”:

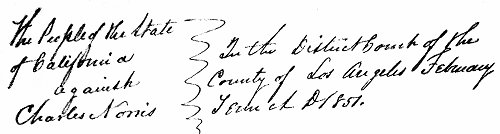

The pleading, you’ll note, is headed, “In the District Court of the County of Los Angeles”:

Actually, the district court was of the First District. Ferrell and Sutherland were district attorneys of that district—but, since the district served both of California’s southernmost counties, they were, necessarily, DAs for Los Angeles and San Diego counties.

![]()

Should Sutherland, the second district attorney of the First District, be included in lists of Los Angeles County DAs? I would think that he should.

The heading on the pleading reflects the common perception that Sutherland was Los Angeles County’s district attorney. Indeed, Ferrell has always headed the various lists of Los Angeles County DAs (as well as lists of San Diego County DAs). Given that Ferrell is credited, without controversy, as having been the first district attorney for this county, it would seem that Sutherland’s name should be inserted behind Ferrell’s in any list of Los Angeles DAs.

The

present holder of the office, Steve Cooley, makes occasional presentations of souvenir

coins on which there is embossed: “Los Angeles County ![]() 36th District

36th District  Attorney.” If you add

Sutherland and Granger to the list of L.A. district attorneys, that makes

Cooley the 38th person to serve as DA (and, in light of some DAs serving non-contiguous

stints, his is the 43rd administration, making him DA #43). On the other hand,

Cooley need not have new coins struck; it remains that he is the 36th man to

hold the office of district attorney of Los Angeles County…the two First

District office-holders, Ferrell and Sutherland, having been DAs for the

county, and serving in the county, but not being officials of the

county.

Attorney.” If you add

Sutherland and Granger to the list of L.A. district attorneys, that makes

Cooley the 38th person to serve as DA (and, in light of some DAs serving non-contiguous

stints, his is the 43rd administration, making him DA #43). On the other hand,

Cooley need not have new coins struck; it remains that he is the 36th man to

hold the office of district attorney of Los Angeles County…the two First

District office-holders, Ferrell and Sutherland, having been DAs for the

county, and serving in the county, but not being officials of the

county.

Under 1851 legislation, effective Oct. 6, each county in the state got its own DA.

Books on the history of San Diego say that when that happened, Sutherland got the post. By that time, however, Sutherland was in San Francisco, engaged in the practice of law.

![]()

“Pioneer Notes From the Diaries of Judge Benjamin Hayes 1849-1875,” published in 1929, does reflect Sutherland’s status as DA for Los Angeles.

Hayes was elected April 1, 1850, as Los Angeles’s first county attorney, having been the candidate decided upon by a “junta” which merely connotes an assembly, not necessarily in a military context. The junta’s decision was influential much in the way the Breakfast Club endorsements today shape the outcome of State Bar Board of Governors elections in Los Angeles. As Hayes (district judge from 1853-64) tells it in an 1854 “retrospect” that he wrote in his notes:

“A secret junta of all the leading Californians, at the residence of Don Agustin Olvera, early in March, selected me as its candidate for County Attorney, an office then provided by law, in addition to District Attorney.”

His recitation continues:

“In September, 1851, I resigned the office of County Attorney, and Lewis Granger, Esq., was appointed. At the election of March, 1850, Col. William C. Ferrell of San Diego, also a nominee of the junta, was elected District Attorney. Afterward Thomas W. Sutherland, of San Diego, held this office awhile, then Benjamin S. Eaton, Cameron E. Thom, etc.”

While Hayes recalls Ferrell and Sutherland as DAs, he leaves out Isaac S.K. Ogier, who came after Sutherland, and he also omits Ogier’s successor, Granger, as well as the next DA, Kimball Dimmick.

Inexplicably, a chapter credited to Hayes in “An Historical Sketch of Los Angeles County California,” published in 1876, does mention Ogier and Dimmick as past DAs, but omits Sutherland, as well as Granger. It is probable that this work was relied upon by historians in ensuing years, accounting for the omission of Sutherland and Granger from lists of DAs through the decades.

It could be that Hayes simply had differing recollections at different times. The circumstances do suggest, however, that the chapter in the 1876 book attributed to Hayes, who died the following year, was ghost-written.

![]()

Such a suspicion finds support in the fact that in the chapter said to have been written by Hayes, there is reference to “a ‘scene in Court,’ one bright afternoon in the Summer of 1850,” described as follows:

“Judge Witherby was hearing an application for bail, on a charge of murder against three native Californians….The Judge, Thomas W. Sutherland (acting District Attorney), Benj. Hayes (County Attorney), Clerk—and counsel, J. Lancaster Brent; present, none others—save twelve, fierce, determined fellows, ‘armed to the teeth,’ huddled up in the far corner.”

There was much apprehension that day; gunplay was anticipated upon the release of the defendants on bail. The narrative continues:

“Preliminaries disposed of—calm content smoothed the face of Sheriff [George] B[urrill]…, when appeared eighteen of the 1st Dragoons, at the critical moment.”

As in scenes in innumerable “B” westerns, the cavalry arrived just in the nick of time. The account goes on to say:

“Bond approved, a Sargent [sic] led the accused outside, placed them on horseback between his files, and so conducted them home: a pin might have been heard to drop, and in the stillness, the Court adjourned. Major E. H. Fitzgerald had encamped the night before, on the edge of town. This was the posse put at the service of Sheriff B., and that left him pleased infinitely at its effect, almost like a charm, upon this famous ‘Irving party’ in the corner.”

The “Irving party” was the gang of one John “Red” Irving which had threatened to slay the defendants unless $10,000 were handed them, which didn’t happen.

There’s no doubt that the incident occurred—though on April 26, 1851, as shown by the minutes—not in the summer of 1850. If Hayes did write the chapter, it’s understandable that he could have been off by a year in his recollection a quarter of a century later. However, it’s difficult to imagine that Hayes, who was county attorney, would have forgotten, if he possessed such degree of alertness as to write a chapter on “Los Angeles County From 1847 to 1867,” that Sutherland was DA at the time. Indeed, Hayes had himself filled in for Sutherland earlier in the month. The minutes for April 15 set forth: “Ordered that Benj Hayes be appointed District Atty pro tem.”

The minutes of June 9 memorialize that Hayes was “appointed District Attorney in the absence of the District Attorney.” He surely knew at the time who the district attorney was who was absent. This is not a bit of inconsequentia apt to be forgotten.

![]()

Whether Hayes did or didn’t write the chapter, it’s certain that it influenced subsequent renditions.

It did more than influence a major work, “Los Angeles: From the Mountains to the Sea” by John Steven McGroarty, published in 1921; McGroarty says that “[b]y reference to an old record we are able to recall” early members of the Los Angeles bench and bar “to memory, as well as to glean some side lights on their characters.” He then reproduces, without attribution, chunks of the chapter in the 1876 book, with some slight changes, these purloined passages including the “scene in Court” and the listing of past DAs.

Noted historian W.W. Robinson, in his 1962 book, “People Versus Lugo,” cites the 1876 “Historical Sketch of Los Angeles County California” as a source. He parrots: “To protect the district judge, the acting district attorney (Thomas W. Sutherland), the county attorney (Hayes), and the clerk, four former soldiers were stationed by the prosecution in the clerk’s room behind the courtroom.”

Other books identifying Sutherland as the “acting district attorney” include “Mexicans in California After the U.S. Conquest by Griffin, Foster and Carlos E. Cortés, published in 1976.

![]()

Lugo was the name of two of the three defendants in the case. They were Francisco Lugo Mejor (Sr.) and his younger brother, Francisco Lugo Menor (Jr.), sons of one of the owners of Rancho San Bernardino, and grandsons of Antonio Maria, alcalde of Los Angeles in 1816, under Spanish rule, and reputedly the wealthiest man in California. The “Lugo Boys” were charged, along with one Mariano Elisalde, of murdering two men in Cajon Pass, located then in Los Angeles County, now in the later-formed San Bernardino County.

News coverage at the time was inflammatory. The Daily Alta California’s April 24, 1851 edition includes “Los Angeles Correspondence” dated April 17, which says:

“The persons committed by [Justice of the Peace] J.R. Scott, Esq., for the murder of two teamsters in the ‘Cajon Pass,’ have been refused bail before the County Judge [Agustin Olvera], and now on Tuesday [April 15] before the District Judge [Witherby]….The two teamsters were Patrick McSwiggen and Sam, both from the Creek Nation, sent out to the quartz mines with a team, and were on their return. The evidence of the guilt of the party arrested is clear. It was a most shocking murder.”

The District Court minutes for April 15 set forth: “Upon hearing the cause the Court refused to discharge the prisoners upon bail and ordered them to prison.”

There was, by the way, no local coverage in Southern California. The first newspaper here, the Los Angeles Star, did not commence publication until May 17, 1851, and San Diego’s initial newspaper, the Herald, was founded 12 days later.

The May 1 edition of the Alta California tells of the three defendants subsequently being “admitted to bail by the district judge in $10,000 each [on April 26].” The article continues:

“The people on hearing it surrounded the prison and declared they should not be released. Major Fitzgerald, with a number of men, being in town on their way up to Sonora, the prisoners were conducted by them to the court, held to bail, and then escorted out of town.”

The May 5 edition adds:

“Recent arrivals from the Desert mines confirm the previous floating reports. Much excitement prevailed at Los Angeles, in consequence of admitting to bail the Lugo family, charged with the murder of an Indian and Irishman at Cahoon Pass.”

![]()

Illumination as to what occurred on April 26, 1851, and on the days before and after that proceeding, is provided in a book with scant circulation and authored by a partisan: the defendants’ lawyer, Joseph Lancaster Brent. Meaningfully, he is commendatory of his adversary, Sutherland.

I’ll tell of Brent’s recollections in the next column.

Before signing off, however, it should be mentioned that the 1876 account in “Historical Sketch of Los Angeles County California” of the 1851 bail hearing, attributed to Hayes, is contradicted by other reports as to the composition of the audience. There were, apparently, a few more persons present than indicated in the book. Among them was Ogier—who would become a district attorney here and later a U.S. district judge—who was assisting Brent in the defense.

Copyright 2011, Metropolitan News Company